5.1 Process

With Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, Dario Buccino sets up a hovering web of possibilities. The score does not provide information for only one way to play the piece but contains a super-abundance of information that must be always held in mind when performing. Predetermining a specific sounding result is not possible, as relations between material, instrument and performer do not rely on an embodiment of actions linked to a specific sounding result. The score does not include fixed pitch material and the left-hand relation to the instrument is susceptible to change through principles of the HN system, obscuring the more conventional mapping of the instrument based on pitch location. Furthermore, Buccino creates an extreme situation of decoupling the hands, their independence from each other, of the hands from the body, and the separation of actions within each hand, all further destabilise the process of embodying. These aspects hinder almost any possibility to imagine the outcome prior to its actual sounding, as discussed in chapter 2.1., but importantly they also radically change the approach to the learning process and memorisation.

The score of Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, rather than representing one fixed whole, is a state charged with potentials that with each interpretation become a unique whole. The fine distinction between the “possibility” and the “potential” is also important here. There are infinite number of possibilities for each identity and how their parameters can be combined and played, which makes it possible for any combination to surface in any of the performances.[1] As a result, the process of learning and preparing the work must be a process of recreating the performance situation. This state of mind goes against “practice room training”.

Practice room training relies on learning through repetition self-critique (invoking what I term a practice-brain) to fix and determine the best solutions (technical and of aesthetic interpretation) that will, in the moment of the performance, be placed in motion. The performance state of mind (the performance-brain) trusts the process the practice-brain did, and in the moment of the performance does not dwell on technical issues and possible imperfections but utilises all the pre-fixed and practised material to deliver the current best possible interpretation. Unlike the practice-brain, which is trained to highlight any mistake or even potential mistakes, and demands from the player to stop, examine, evaluate, repeat, and iron them out, the performance-brain will even consciously give extra effort to hide any shortcomings and, relying on embedded coarticulation and anticipation, deliver the practised interpretation.[2] Rolf Inge Godøy gives further context to coarticulation in music performance practice by listing principles that includes ‘anticipatory cognition’ as a principle of ‘both planning ahead and of actually moving effectors in place before they do their job’,[3] Godøy also speaks about the ‘goal postures or keyframes’ that are specific action trajectory targets related to producing sound and playing music, and ‘contextual smearing’, which implies that there are no clear boundaries between ‘the atom events are made unclear both in the gestures and in the sound, or both in the production and in the perception’.[4] Coarticulation and anticipation that are key elements in preparation and interpretation of most music are, however, absent in Buccino's concept of hic et nunc music-making.

With Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16 there was a need to develop a third type of mental state, a state of perpetual process of the performative situation. Different from the improvisation state of mind, although also characterised by the necessity for high alertness, this is a state where mind and body know in advance each parameter that must go into the performance but must also consciously refrain from any planning, decision making, and anticipation not only prior to the exact moment of performance and throughout the performance. In this mindset it became possible to be ready to present a form without ever experiencing it prior to the performance.

It is, simultaneously, crucial for the performer to clearly refrain from succumbing to an improvisational mindset. Although the outcome of each performance can be completely different, everything about the piece is fixed through the instructions set up in the score. Once completely embodied, the moment of the performance is organic, and thus can appear and evoke for the audience the impression of improvisation. Buccino is aware of this effect and considers it the moment when the performer starts to reach the full potential of interpreting his works. Playing Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16 is therefore a process where practice ≠ rehearsal ≠ performance.

Considering that my approach to the piece advocates for a continuous process, describing how I achieved it needs to be laid out through steps as they were occurring. To be able to create and work within a perpetual process of performative situation, I firstly had to fully understand the score, its purpose, and all the symbols of Buccino’s specific notation.

I received the first version of the score on 9 December 2019; the final score arrived on 14 December 2019. The premiere of the piece was scheduled for 25 February 2020. During the first day of working with the score, I first had to understand how Buccino uses space and time as parameters, which I previously encountered only as concepts in the initial two-day exploratory working session with Buccino.[5] In Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, time is a parameter of the non-hierarchical structure that is defined but non-fixed or binding. To this, Buccino adds space as a parameter with a similar behaviour.

The space as parameter is present in the piece in three forms:

- 1. The score is spatially organised (see chapter 2.1.1.)

- 2. Spatialisation of the body:

- a. Spatialisation of performer’s inner body on the level of notated (in HN style) distribute of centre for sourcing energy and peripheral (the limbs)

- b. Spatialisation of the instrument itself: mapping of the instrument, both the violin and the bow, in relation to points that can be sound sources

- c. Spatial relations of the performer’s body and the body of the instrument understood as one collective body

- 3. Use of physical space in which the performance is taking place as a musical element and participant in construction of the form of the piece.

The temporal element is conceived in a similarly non-linear way. Whilst Buccino gives rough lengths of time per page, the durations of identities within the page and the sequence of their appearance are subject to HN and the moment of performance. Buccino adds that these durations can also be influenced by HN if the performance situation leads to it. It is also possible to come in and out of the same identity multiple times within the bar. Lastly, Buccino adds that it could also be possible to jump back and forth between pages (again if HN determinants this occurrence in the moment of the performance).[6]

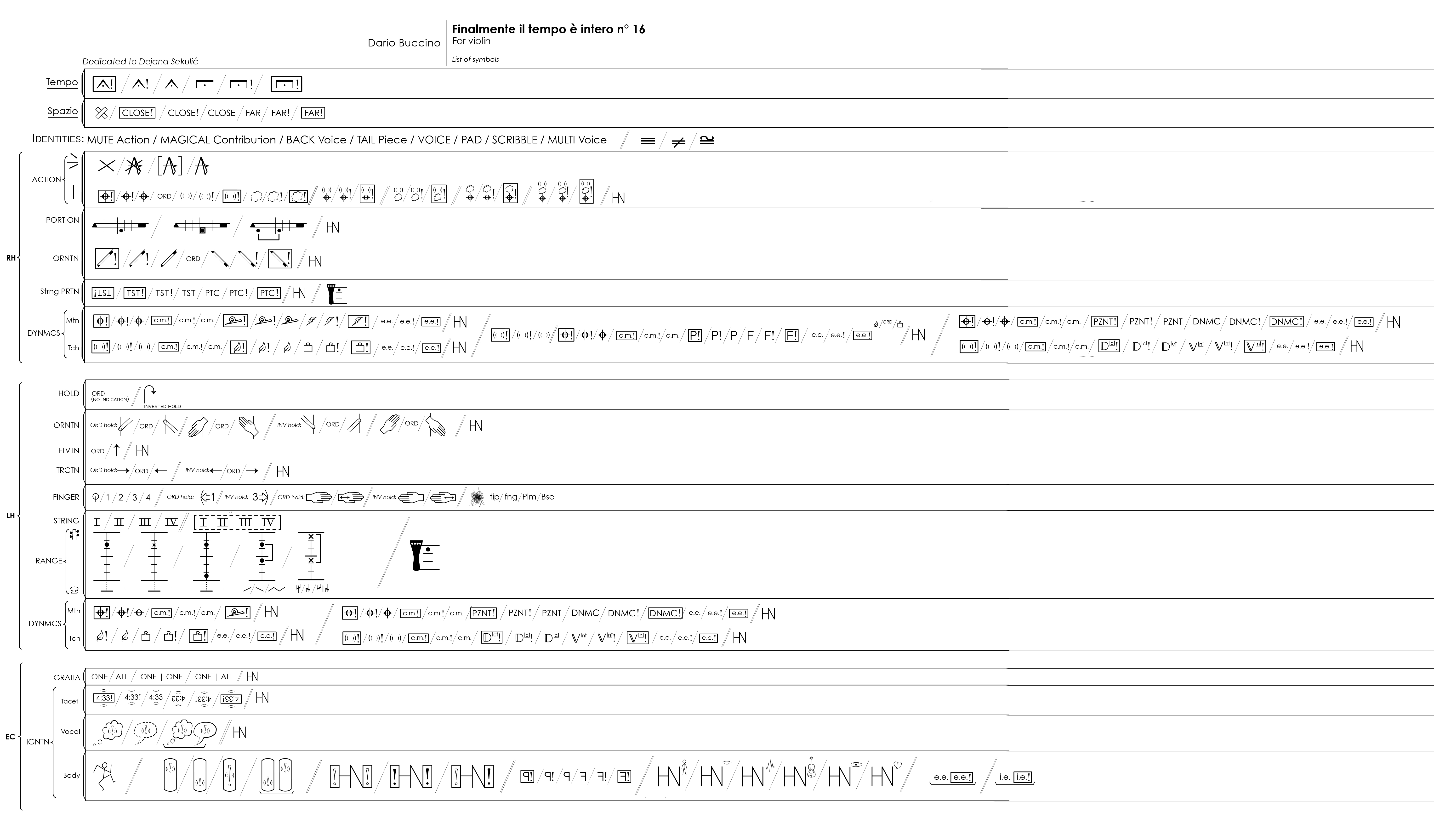

With a better grasp of the basics of the score and with an understanding of the fundamental concept of hic et nunc (HN), the next imminent step in my work process was to learn the meanings of the score’s many idiosyncratic symbols. The initial score didn’t include a legend, and it became evident in conversation with the composer that it would take a while for this list to be compiled for the final score[7], so my next step was to compile the list of symbols myself (see figure 5.1.1), using my notes from the initial working session and the score.

Figure 5.1.1: self-compiled list of symbols used in preparation of the piece, December 2019

As it can be seen in the example of page 9 (figure 5.1), the HN symbol can appear in almost any parameter of any sub-bar. Each HN stands for all the potentials and gradations of that specific parameter. Full table list of definitions of symbols I derived from the notes from the two work sessions with the composer and subsequent conversations has been presented in chapter 2.1.1, and can be seen in figure 2.1.1.2.

Learning Buccino’s specific notation was a necessary microscopic investigation into the piece, but it also set off a change in macroscopic perception of the piece’s material, its potentials, and how to approach the challenge of interpretation. As George Armitage Miller writes, ‘in our perception there is a transformation or “re-coding” of complex sensory information into overviewable units, reducing the memory load and enhancing our ability to cope with large amounts of information’, and this was exactly the effect my first step in the process, decoding of meanings of the symbols, achieved.[8]

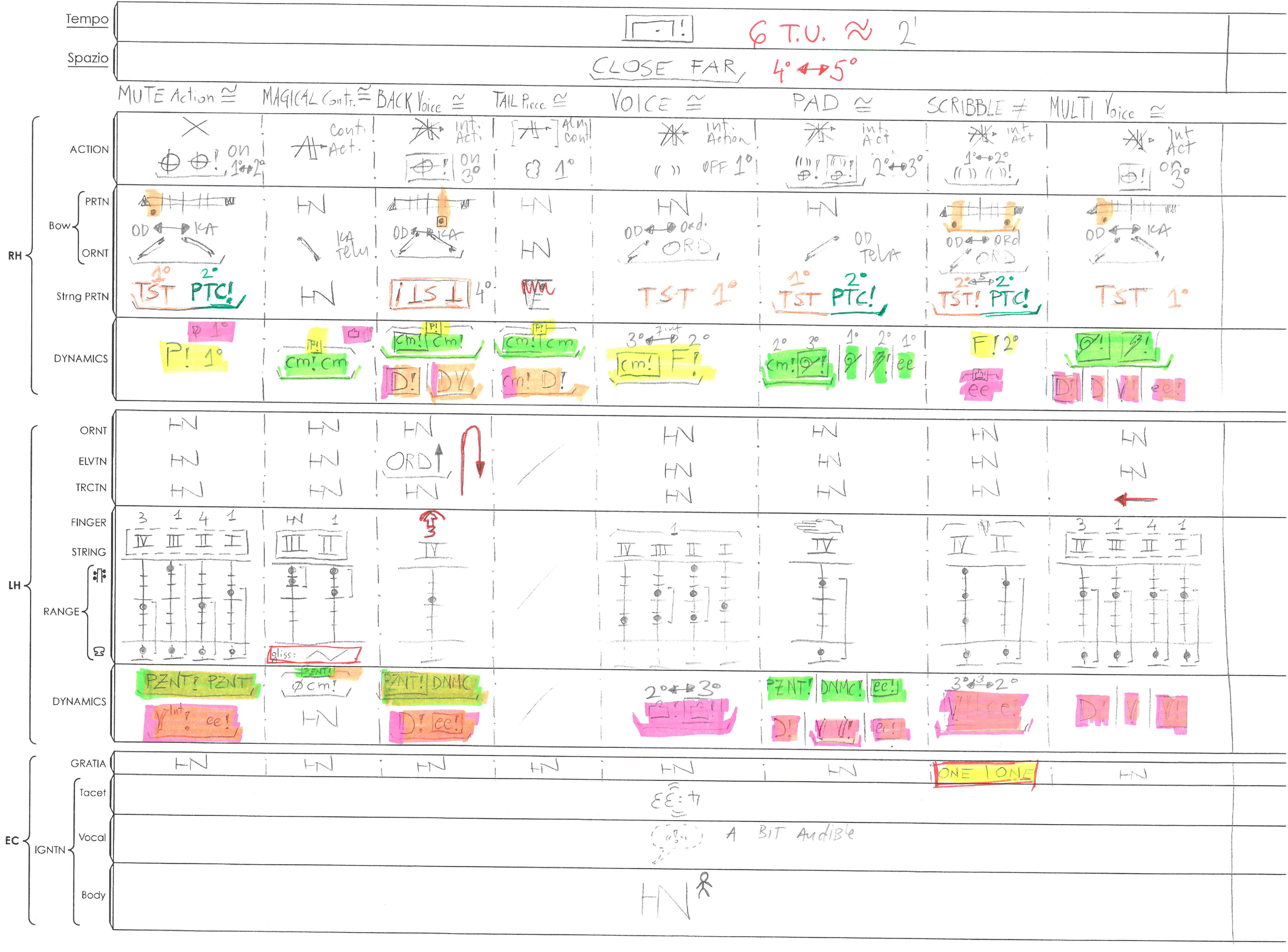

To further help me navigate the score in practising, I chose to colour-code the score. This is a practice I employ often, especially in contemporary music pieces, and is a widespread practice in which each performer creates their own ‘structured colour code’ system.[9] Although I try to be consistent with a general colour system applicable across different pieces for the sake of fast recognition (for example, green will often be used for sul ponticello bow placement, orange for sul tasto, while light blue would be assigned to area of ordinario bow placement), tuning the general system to the necessities of a specific piece amplifies the impact. With the number of particularities and detail in Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, I also realised that having too much colour would diminish the purpose of using this method for visual organisation. It was also important in this case colour-coding that did not start to place more importance on some information than others, thus creating hierarchy.

The solution I came up with was to use some general markings with ballpoint pen and thin highlight, and to give thick highlighted stripes to the parameter of left- and right-hand DYNAMICS. I found that the level of detail in respect to dynamics being applied individually to speed of motion and touch, volume, and affection of motion and touch was more unfamiliar, thus I found that this approach created an equal balance with aspects that felt more graspable. The code I created was:

- • Red ballpoint: diverse specifics including time and space, and also details about the orientation of the hand position, when traction or playing with the finger under the string was determined, glissandos

- • Thin orange highlight: bow portion

- • Thin yellow highlight: endocorporeal, with use of red ballpoint when need arises

- • Thick green highlight: dynamics–movement–speed for both right and left hand

- • Thick pink highlight: dynamics–touch–weight/pressure for both right and left hand

- • Thick yellow highlight: dynamics–volume for both right and left hand

- • Thick green-orange highlight: dynamics–movement–affection for both right and left hand

- • Thick pink-orange highlight: dynamics–touch–affection for both right and left hand.

The result of this process can be seen in Figure 5.1.2.

Figure 5.1.2: Colour-coded page (no.6) of Dario Buccino’s Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16

The next step in the process of work was finding a system for practising in which each of the parameters could be explored sonically, gesturally, and with regard to the parameters of energy distribution, but without this leading to a fixed pattern or melody that would be memorised. While Buccino speaks about his music being based in a melodic concept, this melody is not inherent nor hidden in the piece itself. It is the concept of melody and melos[10] that he desires each performer to seek. This hidden melody is revealed to the performer in the moment of performance through how the material is interacting among itself (different identities) and with the space and with it shaping the form. It is then that the performer must pursue the melody and its development in eight different ways through individual development of each of the identities and through the overall flow of the piece. In this sense, the process of practising is not a process of learning a melody but of preparing oneself to continuously seek a conceptual melody, enacting melos.

What this means for the technique of playing and practice is that even if the outcome might be perceived with the elements of ‘mass-spring systems’ and of ‘contextual smearing’,[11] ‘where the sounds of successive excitations linger on and fuse into more composite sonic objects’,[12] every atom event must remain clearly individual, unattached to the other, keeping its own full spectrum of characteristics and always ready to change. This resulted in developing sets of mechanisms for small individual components to be explored, to be “practised”, but in a way whereby none of these components gets fixed nor becomes dominant. Arriving at a dominant component would lead to hierarchisation of the material, and with any sign of this the intention of the piece falls apart.

In my approach I relied on the following set of mechanisms:

- • Practising each parameter through all of its degrees, as a separate variable to grasp some of its potentials and to ensure independence of hands from each other and from the body. My experience has proven that there is always more potential that can be individually anticipated; there is always some novel or different outcome that appears in the moment of performance from unexpected connections between these parameters. This mechanism was applied on each element of the right hand separately, on elements of the left hand, and elements of the endocorporeal actions separately. Some practising was also done without an instrument, but soon it became clear that was not a good approach. Even if only working on inner endocorporeal energy influences, having the instrument in the hands changes the body itself. The instrument is part of the body as much as the body becomes part of the instrument. Recording in figure 5.1.3 shows an example of working on moving the right hand by not focusing on mentally sending energy directly to the outer limbs to move but rather focusing on inner body, a stomach area, as the source that would eventually create and result in some movement.

Figure 5.1.3: Exploring and working on moving the right arm using the energy from the stomach

The only parameter that is truly not possible to explore on one’s own is the GRAZIA parameter, as this parameter demands people to be present. I resorted to try-outs that included imaginary people and imaginary energy exchanges (especially in the next phases with mechanisms working on sub-bars/identities, bars/pages, and piece-runs), but always with understanding that this is not the real effect nor experience – and my performances have proven this to be correct. The following recordings (figure 5.1.4 and 5.1.5) are examples of two of the processes in practising. The parameters in these examples are:

- ◦ in 5.1.4: Right Hand – Action – Vertical:

- ◦ in 5.1.5: Left Hand – Dynamics –Touch – Weight/Pressure:

Figure 5.1.5: Exploring and working focus: left-hand touch, weight/pressure

- ◦ in 5.1.4: Right Hand – Action – Vertical:

- • Practising individual sub-bar (identity) separately, as found in the score, without application of Tempo (duration). There is a gradation in practising with this mechanism:

- ◦ Start by practising the sub-bar (identity) only by activating fixed parameters

- ◦ Add HN parameters for one area at a time, while keeping the others intact

- ◦ After playing for some time the sub-bar with all fixed and HN parameters active, introduced a change of only one parameter

- ◦ Try to consciously return to the state before the change of one parameter and then change another one

- ◦ After playing for some time the sub-bar with all fixed and HN parameters active, start changing one by one all the HN parameters

- ◦ After playing for some time the sub-bar with all fixed and HN parameters active, start changing one or multiple HN parameters

- • Practise the same identity from another non-consecutive page, with different parameters. Concentrate on understanding and registering the differences and nuances; think about whether there is a noticeable progression gap in what could have happened in the pages skipped.

- • Attempt going from the beginning to the end only with one identity, applying Tempo (duration) proportions but not full durations. It is important not to plan or anticipate a melody line, but to notice how it builds on its own from whatever the active parameters and HN bring in the moment.

- • Conscious “non-memorisation”: consciously avoiding memorising combinations of possibilities that sounded or felt good revealed itself as an important element in the process. It was especially important to train non-memorisation of relations between the appealing sounding result and gesture that produced it in the moment. What I tried to internalise were the sensations and experiences of how certain sounding elements and timbres felt and embodying that feeling as if it was sound. And separately internalising the feeling and sensations of energy and its potentials in relation to the feeling of thinking a gesture and making a gesture.

- [1]On what constitutes identity in this case, see chapter 2.1.1. [Please see full Thesis, available via University of Huddersfield's repository.]

- [2]In linguistics, David A. Rosenbaum explains coarticulation through the example of ‘anticipatory lip rounding’ to ‘illustrat[e] a general tendency that any theory of serial ordering must account for – the tendency of effectors to coarticulate’; he continues to define coarticulation as ‘the simultaneous motions of effectors that help achieve a temporally extended task’. David A. Rosenbaum, Human Motor Control (San Diego: Academic Press, 1991), p.15.

- [3]Rolf Inge Godøy, ‘Coarticulated Gestural-Sonic Objects in Music’, in New Perspectives on Music and Gesture, ed. by Anthony Gritten and Elaine King (New York: Routledge, 2011), pp.72-73.

- [4]Godøy, ‘Coarticulated Gestural-Sonic Objects in Music’, pp.72-73.

- [5]The initial two-day working session took place in Milano (Italy), Buccino’s city of residence, on 10 and 11 April 2019. The work with Dario Buccino comprised of conversations about his compositional practice and process, notational language and symbols he has developed, ideas and directions for the piece. Furthermore, our practical work during this session was based on initial explorations of two pages of material he has prepared for this occasion but also already deferring from them. Thus, already from the very first contact the “going beyond of the score” principle was established as a norm.

- [6]This is further information that has been repeated in almost every conversation and work session with the composer, but also given as explanation during a seminar-lecture about the piece we jointly gave on 2 April 2022, in Conservatorio di Palermo in Italy.

- [7]The three-hour working session took place on 23 December 2019, via Skype.

- [8]George A. Miller, ‘The Magic Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on our Capacity for Processing information’, Psychological Review, 63.2 (1956), pp.81– 97.

- [9]Ine Vanoeveren, ‘Confined Walls of Unity: The Reciprocal Relation Between Notation and Methodological Analysis in Brian Ferneyhough’s Oeuvre for Flute Solo’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, UC San Diego, 2016), p.87.

- [10]Dario Buccino uses the word melos to explain his approach and his own understanding of in what way his music is melodic. He pairs melos with melody in his explanation and emphasises that of course melos in a musical context means melody, but that that meaning came later in history. His liking for the word as a good container to explain his approach is due to its ancient Greek meaning of ‘limb’ or ‘body part’. This in turn has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European root *mel-, which stands for ‘part of a whole’, and which relates to the notion of combining such parts. The later coincidence of meaning between melos and ‘melody’, he says, is only a plus.

- [11]In describing coarticulation principles in music, Rolf Inge Godøy talks about contextual smearing and mass-spring models. The former is as a happening where the boarders between individual actions of production and perception of sound become blurred and these individual atom events loose many of their individual characteristics and features. The latter refers to uneven use and distribution of energy when producing sound.

- [12]Godøy, pp.72-73.