CHAPTER 5 Learning Methods, Rehearsal Processes, and Memorising Unfixed States

‘People get really upset about form if it doesn’t quite cohere. Unity and stuff like that. There’s no sound that anyone can make that really upsets anyone. We’ve heard all the sounds. But form really upsets people: if it doesn’t make sense, if it doesn’t cohere. It was perhaps tongue in cheek, but Christian Wolff said to me once that his definition of form was “one damn thing after another”.’ – Philip Thomas[1]

In this chapter I will focus on the third challenge area, process and memory, that impelled me to find new rehearsal methodologies for how the mind and body can be trained to remember and embody complex and densely superposed material in music. The main discussion will be based on Dario Buccino’s Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, which is a piece without a predetermined fixed form and therefore becoming only in the moment of the performance. In the final portion of the chapter, additional observations and examples will be drawn from the work on pieces by John Cage (Freeman Etudes), Miika Hyytiäinen (Impossibilities for Violin), and Evan Johnson (Wolke über Bäumen).

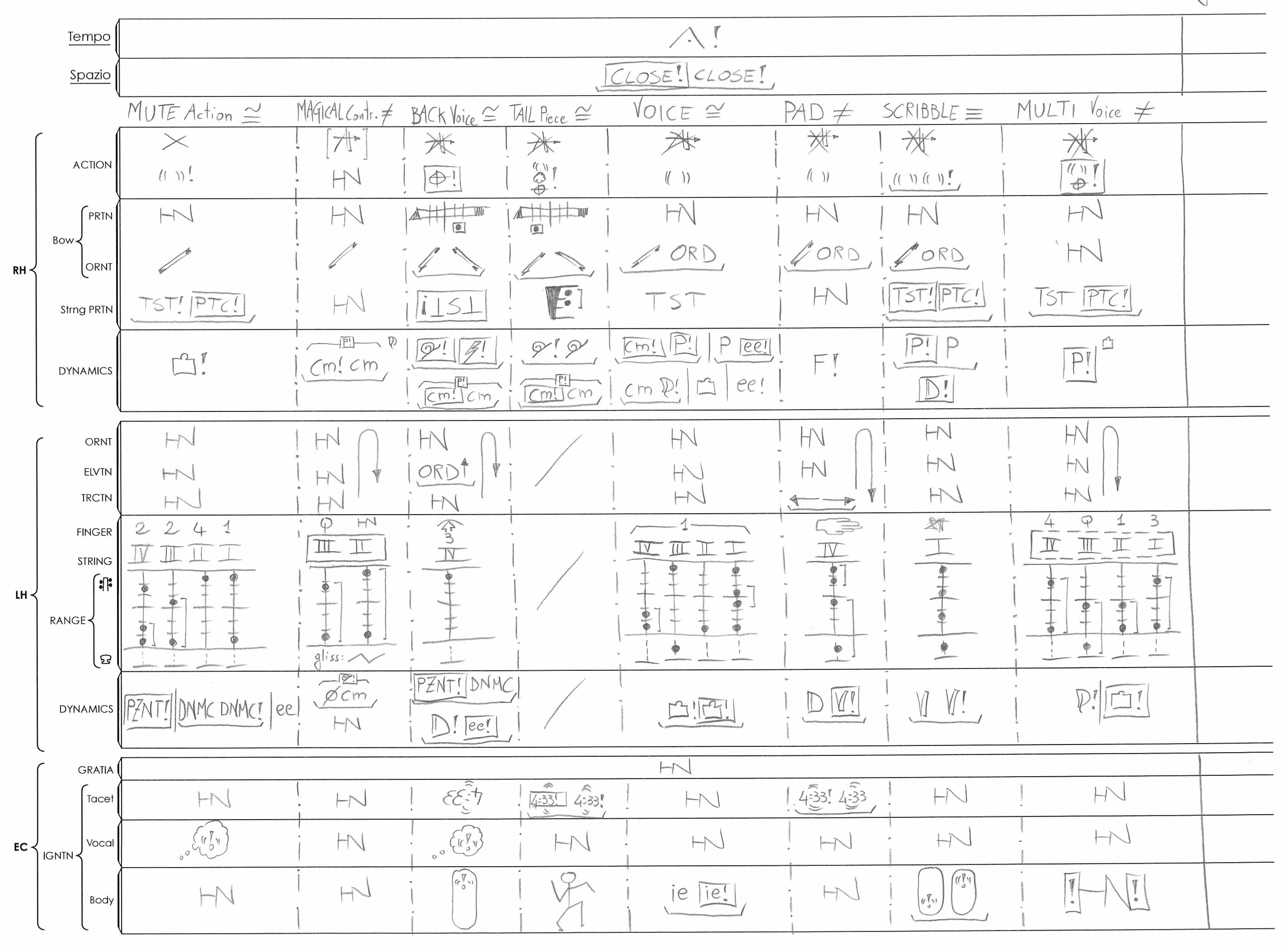

Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16 is a piece that does not have its one performance version and form, and all the material in it stands equal to each other. It is only in the moment of the performance, with philosophy and concept of hic et nunc (HN system), where the material starts to mould itself and one performative iteration of the piece emerges.[2] In my own process of learning it, the piece demanded that I reshape my approach to practice so that every detail of its rich but complex nature would still be present without any gaining dominance, where ‘the point is not to render ideas less complex – the point is to make the complex clear’.[3] The first encounter with the score of Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16 raised questions for me of where to start the working process, and it even became clear that I would also have to address the issue of how to begin the piece in performance.

Buccino developed a specific notation that facilitates his non-hierarchical material to remain free of fixed form, while still managing to give a frame within which the performer can begin to act. The notation and symbols are not events or specific sounds, but rather circumstances and states that will lead to the emergence of those events and sounds out of their combinations created in the moment of the performance.[4]

Figure 5.1. Dario Buccino’s Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, page 9

This approach is a sharp departure from a more conventionally written western classical violin pieces with the highest level of difficulty, there is a linear passing and sequencing of events that makes for graspable development of coarticulated gestures, anticipation, and performative holistic perception of the flow of the piece. For example, in some of the fiendishly demanding solo pieces from the standard repertoire such as Paganini’s caprices, or the Chaconne from Bach’s D major Partita, or Ernst’s The Last Rose of Summer, even the trickiest of passages have their left- and right-hand actions linked to a common goal of expressing pitch-based melodies. The material flows in a forward-moving linear direction. Sections of works that have to be extracted for honing their execution, once practised and perfected, fit within the whole piece, in the exact same state and sounding the same way as when they were practised. The directionality of the music allows for memorisation and anticipation of exact sequences of hand actions and of the sounding results of those actions (pitch and sound quality and characteristics combined) in a linearly constructed interpretation and enables linear memorisation of the piece as a whole. The more complex and excessively dense writing encountered in my focus repertoire (in the works by Johnson, Cage, Cassidy, and Ferneyhough) already presents a challenge to coherent construction of the sequencing, and thus to memory, given the unpredictability of the outcome once interpretative actions are put in motion. Construction of sequencing and anticipation of events through memorisation of the whole performative outcome, becomes infinitely more difficult once even the linear passing of events is removed from the structure (as in the case of Buccino, but also Hyytiäinen). The "unpredictability of outcome" in all these cases relates to the relationships between techniques of playing and sounding, mapping of the instrument and positions, and gestures.

While works of Cage, Hyytiäinen, and Johnson present challenges to process and memory to those accustomed to the more standard repertoire, it is still possible to find a hierarchy of material within each of the pieces. This greatly helps in how the process is guided, and how — although there are unpredictable elements that can influence the outcome in the moment of the performance — understanding the hierarchy serves as a safety net. In the following part of this chapter to further probe the challenges of pieces in which there is no hierarchy of the material I will focus on Dario Buccino’s piece Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16.

- [1]Barry, Robert, Visceral Communication, interview with Philip Thomas (February 4, 2020) https://van-us.atavist.com/visceral-communication [accessed 25 May 2023].

- [2]HN system has been explained in detail in chapter 2.1.1. [full Thesis available via University of Huddersfield repository]

- [3]bell hooks, Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work (New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1999), p.40.

- [4]For more on Buccino’s approach and concepts see: Dario Buccino, ‘Writings: Articles’, (2006-2009), http://www.dariobuccino.com/creative/works-eng/writings-eng/articles-eng.html