1.2.2 Equalising the Optics of the Space: reading the “blown-up” segments

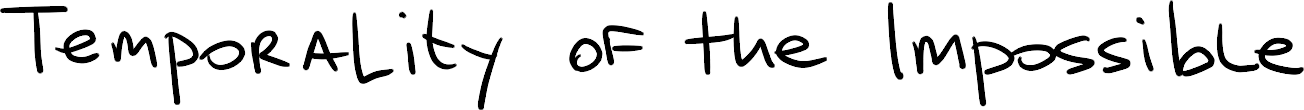

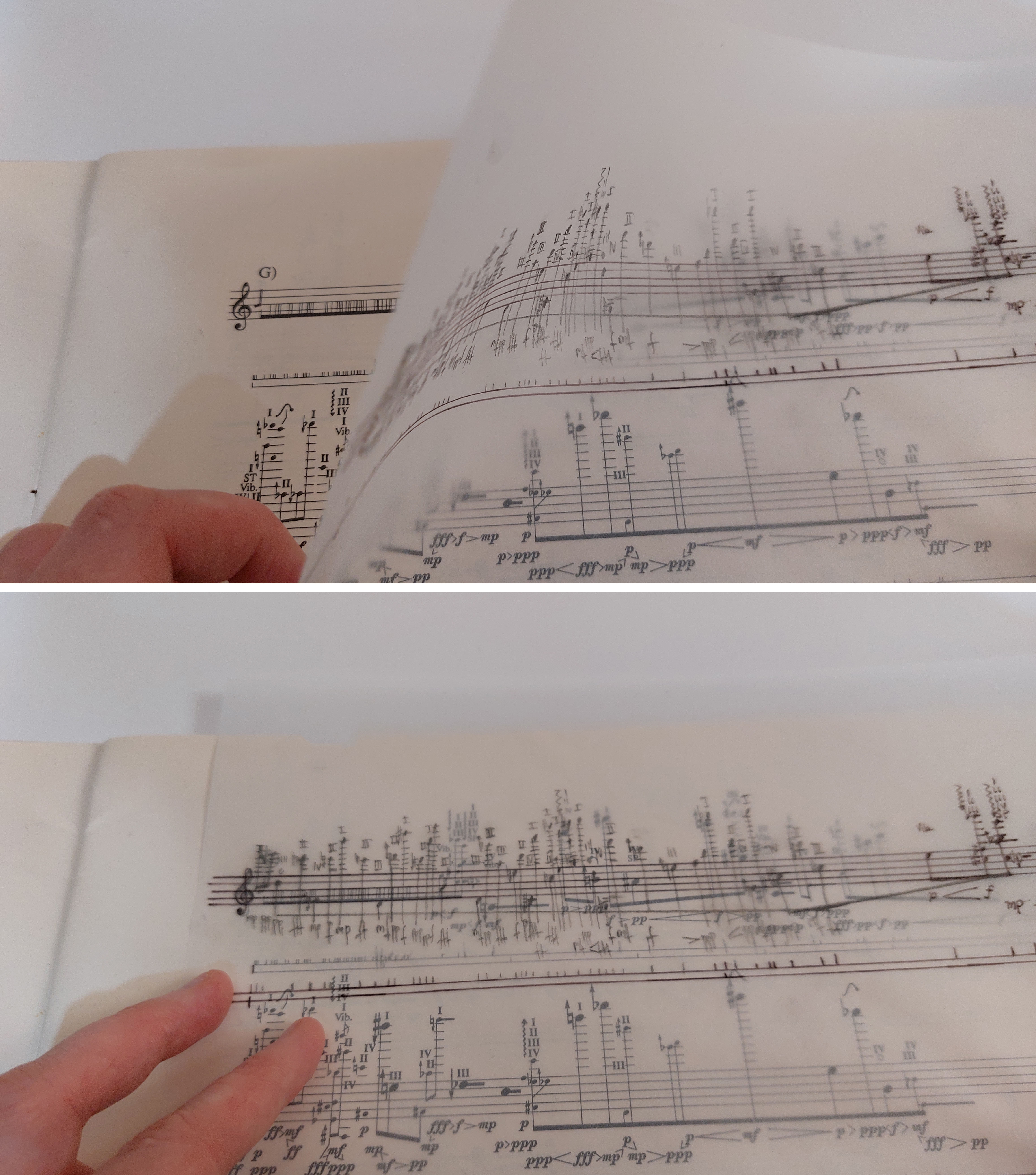

As described in Pritchett’s report, one of the first and main givens for the piece, that was decided before any of the notes/pitches were generated, was organising of the spatial layout of the score.[1] The second operation in the chance process – that of deciding pitches – started accumulating a significantly larger number of notes per bar, so much so that there would not be enough space to write them all properly in their respective spaces. Etude XVII is the first instance in which ‘out of place’ additional segments of notes can be noticed, appearing above the main staff (figure 1.2.2.1). In order to make legible the segments for which too many notes have been assigned, Cage puts only stems to mark the ictuses, moments when each of the sound events is going to happen within the bar. There are no noteheads, nor any of the additional characteristics. To actually notate the sound events, the “blow-up” segments appear, in most cases, relatively close to their original place.[2]

Figure 1.2.2.1: Excerpt from Etude XVII

As seen in figure 1.2.2.1, these segments are marked with letters; these additional groups of notes represent the corresponding letter segments from the main system. It is easy in this example to make this connection also because the segments appear relatively close to their original place, but this is not always the case. In the case of Etude XVII, these break-out sections are much more extreme.

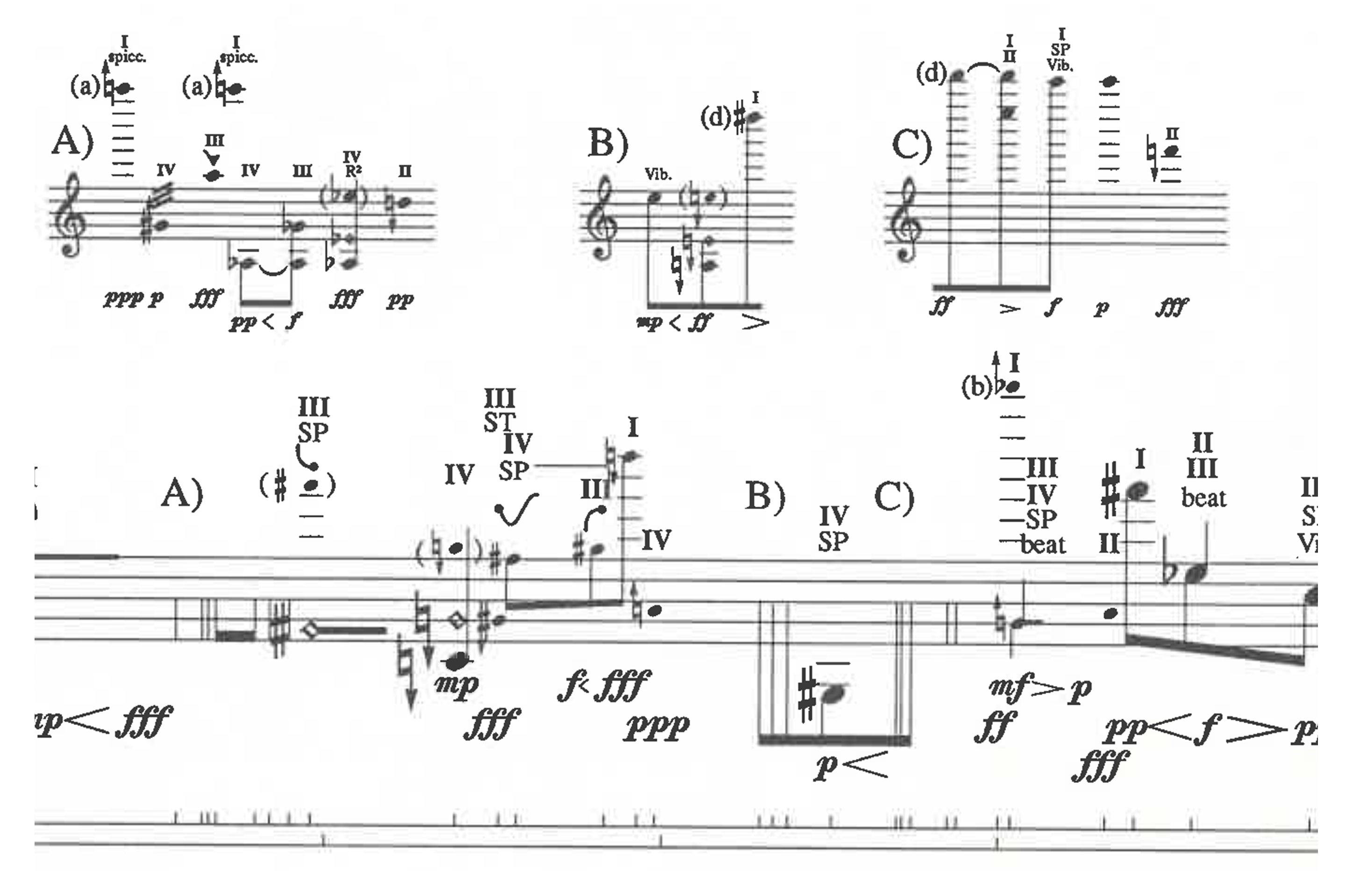

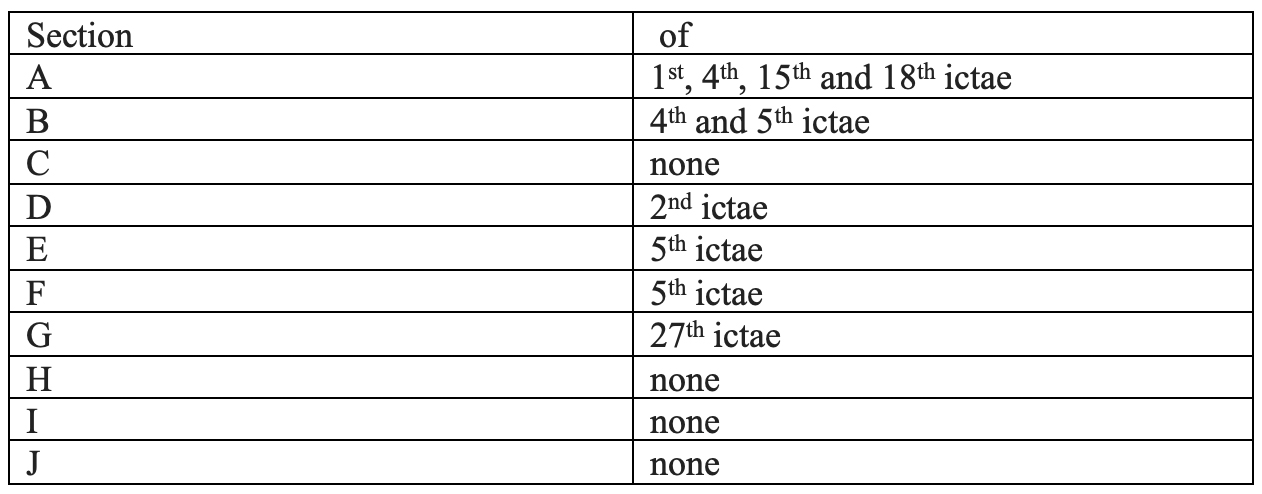

Etude XVII has ten such segments, marked A to J (figure 1.2.2.2). The number of ictuses that appear in each of these segments are:

Figure 1.2.2.2: Number of ictus appearances per segment in Etude XVIII

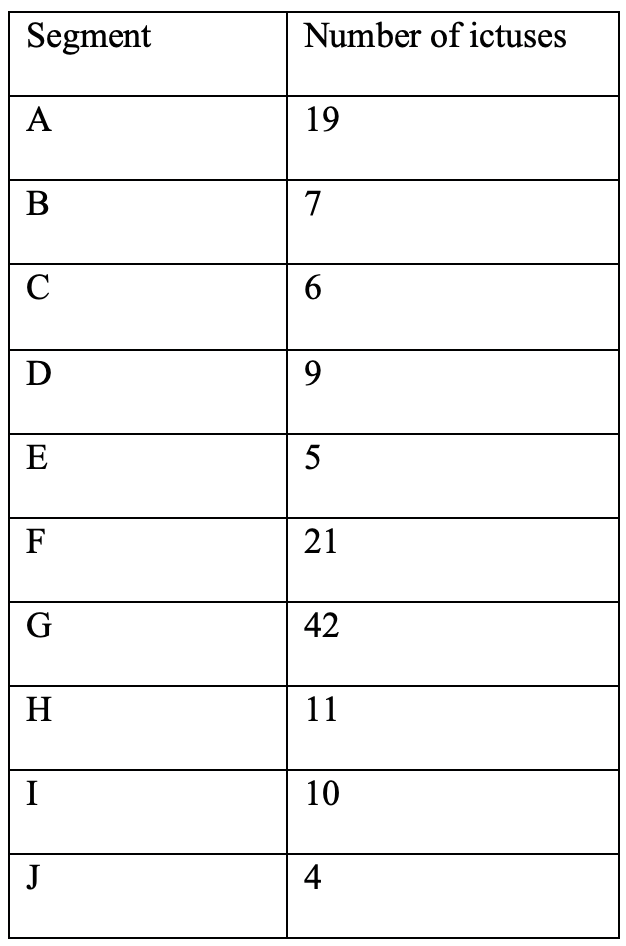

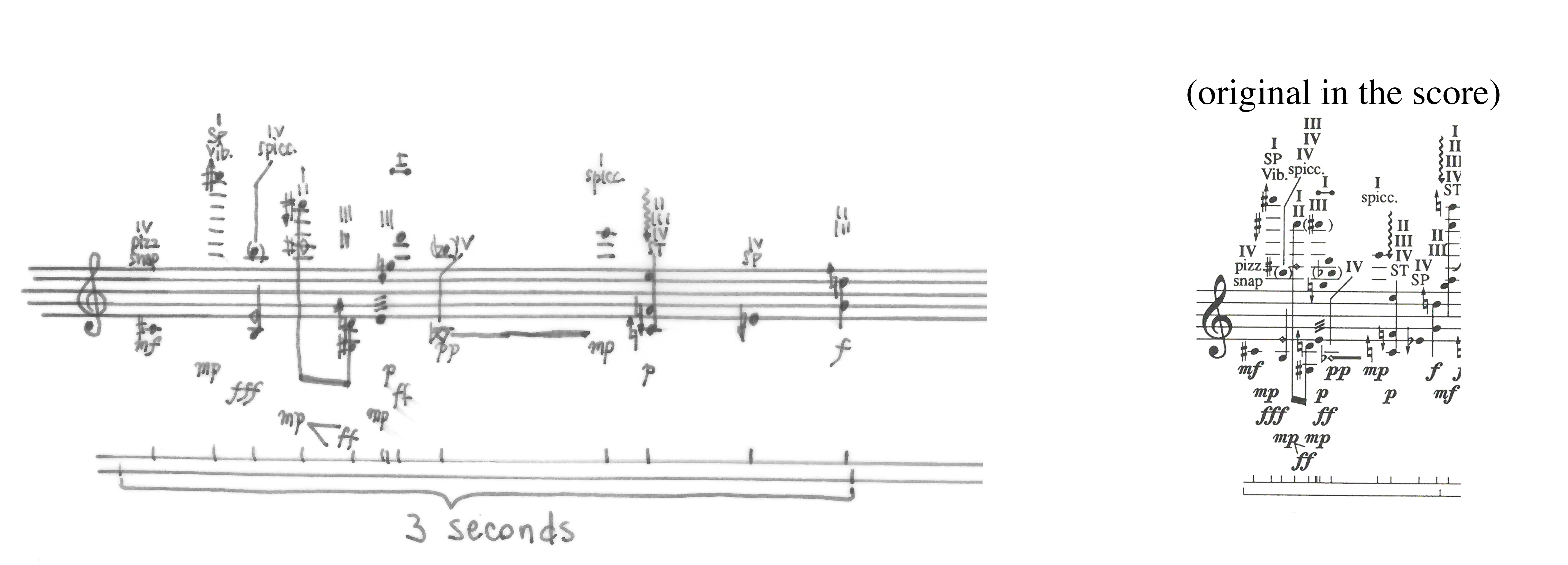

When starting my own preparation process, the discrepancy of scale in augmentation of the segments (of “blowing up”), as well as their placement in the published score, revealed an issue. For a piece that relies on space-time notation throughout, the “displacement” of material can be considered a problem from the standpoint of grasping all the musical intentions and continuity. For example, even the simplest visual rendering will show that the proportion of the enlargement of segment A does not correspond to that of segment B (figure 1.2.2.3).

Figure 1.2.2.3: Example of uneven spatial representation of condensed material on the second line of Etude XVIII

The purpose of the “blow-up” sections had the sole goal of making the notes legible, but in doing so this representation removes the sense of proportion. In addition, there seems to be no specific rule according to which they are ‘blown up’. According to Pritchett, Cage did not have any involvement in the depiction of these ‘blow-up’ segments and how they were going to appear in the published score.[3] They were notated on separate, uncategorised pieces of paper and simply copied in a “legible” way by a copyist. Even if a performer is conscious of this trap, it seems an unnecessary addition to all the other parameters that one has to deal with.

One solution could be to learn the segments by heart, which will inevitably happen over time to some extent. But because of the nature of the composition, performing without the score, however impressive, might risk giving the audience an impression of improvised music.[4] In addition, in segments like G, the sequence consists of 42 notes that are to be played in a little less than 4 seconds. This segment is where Cage's instruction – ‘the violinist, omitting when he must, should play as many ictuses as possible’ – applies most.[5] Learning this segment by heart with a predetermined note sequence and permanently disregarding the others, although not impossible as a solution, would be to forgo the ‘practicality of the impossible’ and the continuous personal development that comes from engaging with it. The presence of the score allows for this segment to still change, evolve, over time.

It is with this readable context-directed aspect in mind that a representation with a more proportional scale applied for each segment could give a better overall understanding and possibility for navigation through these segments in the piece. For example, the second system of Etude XVIII (of which an excerpt is shown in Figure 1.2.2.3) is 22.24cm long, or if we measure just from the beginning of the first to the end of the last bar 21.35cm (i.e. seven bars of 3.05cm). One bar should, according to Cage’s instructions, be approximately 3 seconds long. As seen in figure 1.2.2.3, segment A in the main score occupies approximately 1cm of space. When blown up for reasons of legibility (figure 1.2.2.3), the segment occupies 5.6cm. Segment B in the main score occupies approximately 0.3cm, and its augmentation measures 2.2cm. This means that segment A was enlarged by 5.6 times, segment B by approximately 7.33 times. If section B were enlarged proportionally, by 5.6 times as for section A, it would occupy 1.68cm. As it can be seen in figure 1.2.2.4, making this proportional enlargement would still make the segment legible, yet it would also maintain visual-spatial consistency with section A in terms of their relationship to the main staff line.

Figure 1.2.2.4: Segments A and B from Etude XVIII, my handwritten proportional enlargement

Segment G is especially problematic, and not only for the fact that it appears on a different page from the corresponding part of the main staff line. In the main staff, the last ictus of group G is beamed to the next ictus. In the blown-up representation, this beam is significantly shorter than its original and does not therefore represent a performatively usable duration. Segment G occupies 3.69cm in the main staff and 13.6cm in the blow-up, making this approximately 3.69 times augmentation, in the proportion that renders segment G legible.

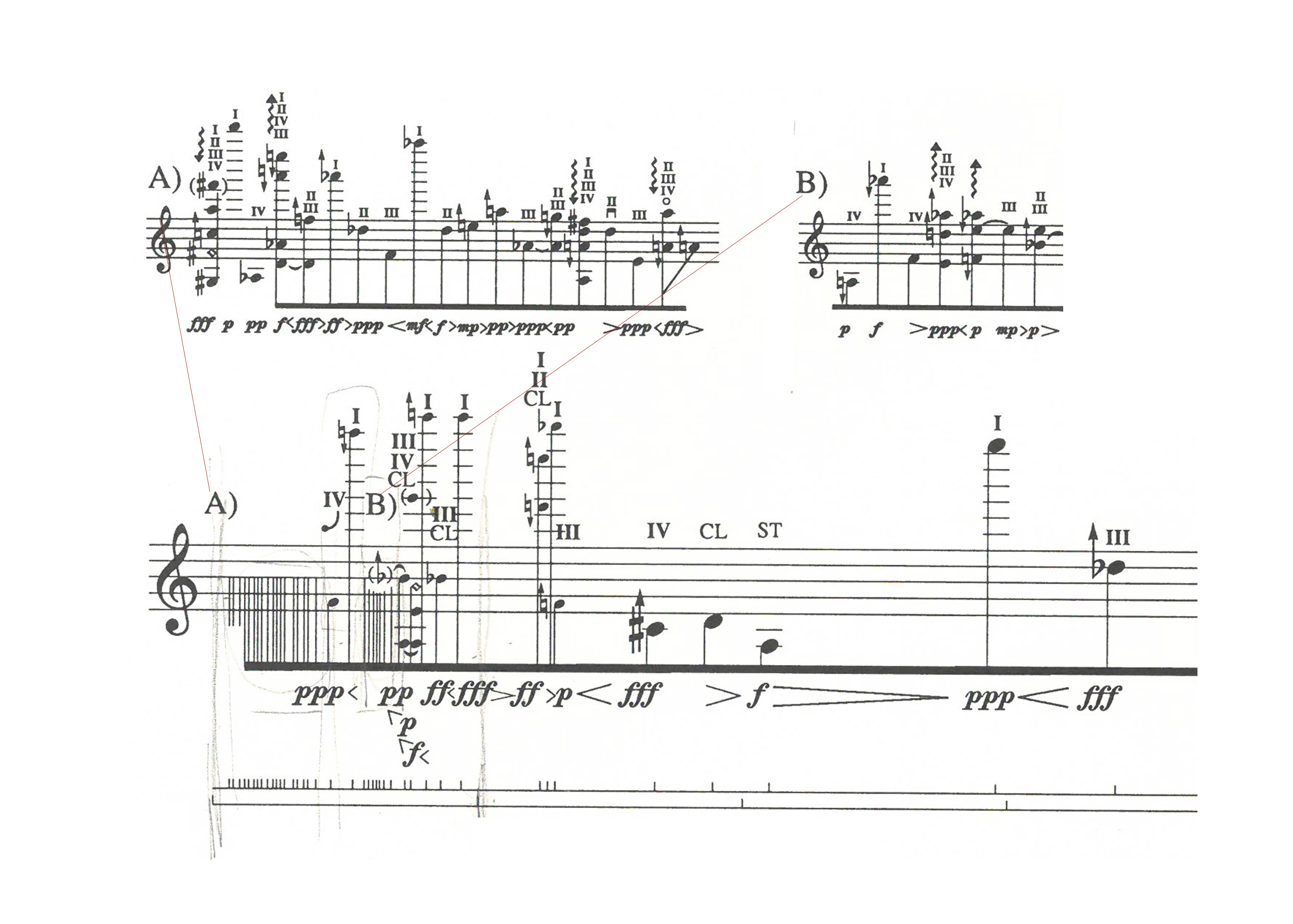

In the score, the blown-up sections do not have any representation of the different distances between ictuses, whose existance can clearly be seen in the main timeline for sound events. This means that the blow-up segments in the score do not include information on durations, as can be seen from example in Figure 1.2.2.5 where blown-up representations do not follow distances between the notes in the way they appear in the main system.

Figure 1.2.2.5: Segments C and D from Etude XVIII

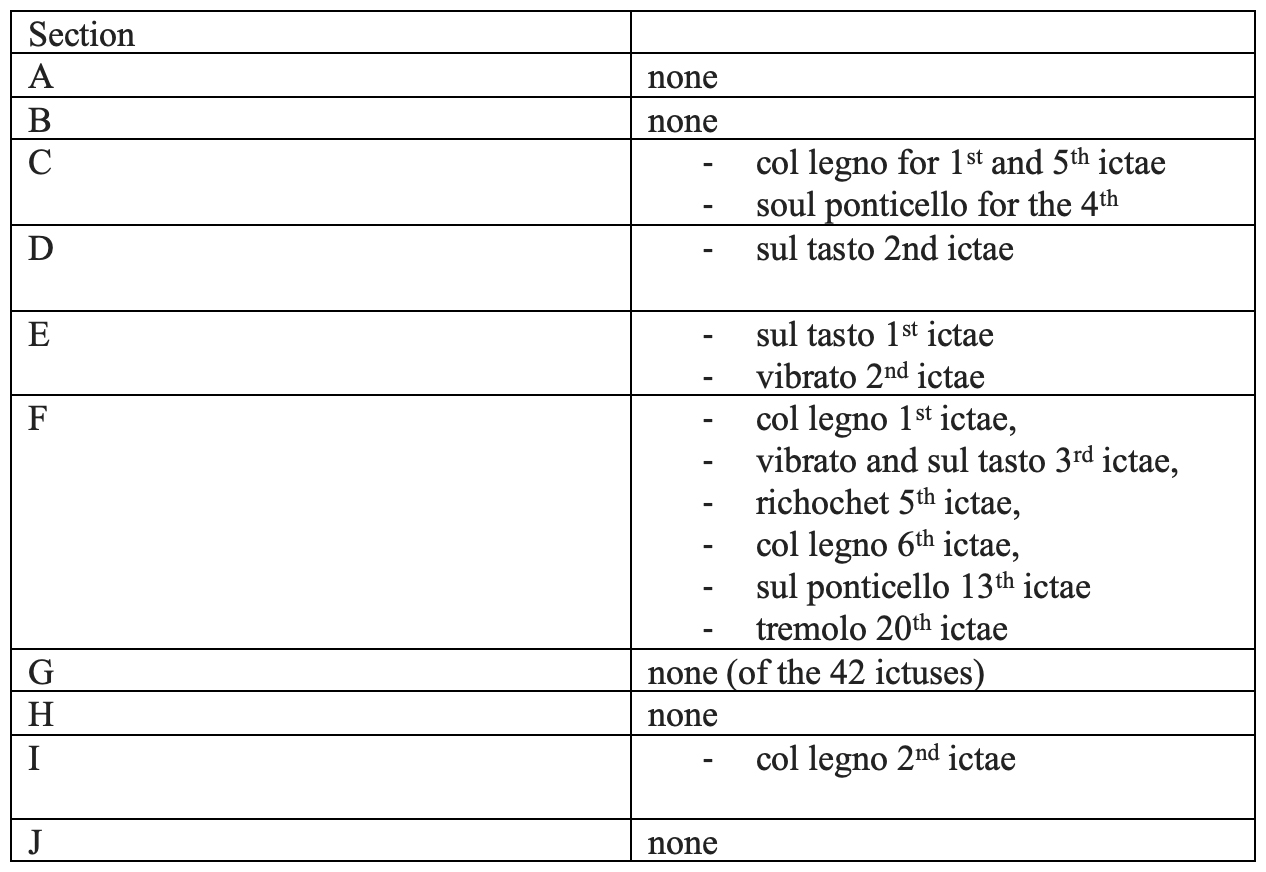

It is inevitable to have these blown-up segments. But a greater degree of proportionality in the augmentation for segments A–J would be better maintain the original score’s principle of space-time division and its musical intentions, and would enable the performer to more easily imagine the relationship of the ten segments within the overall form. My approach, to re-notate segments A-J having in mind time-space proportion and durations (example can be seen in Figure 1.2.2.6 on segment G), does not infringe on the authenticity of the score or the compositional process since, as previously mentioned, Cage himself did not write them in the way they appear in the published score.

Another possible aid to understanding the spatial and temporal relationship between these segments and the piece as a whole would be to augment the entire etude to the scale of the blow-up letter segments. An example of proportionally applied augmentation to the sixth line of the etude – which contains the longest segment, segment G (itself shown in figure 1.2.2.6) – would measure approximately 78cm in length (figure 1.2.2.7 and 1.2.2.8).

Figure 1.2.2.6: Segment G from Etude XVIII – my handwritten augmentation

Figure 1.2.2.7: Photograph of the augmented sixth line of Etude XVIII

Figure 1.2.2.8: Superposition of tracing paper with legible section G and the original

With this complete augmented excerpt from the score I in no way intend to propose a rewriting of the original score for creating a more “convenient” performance score. Such a score on its own, as a performance copy, would be problematic and impractical for several reasons. If such a score were to be printed, it would be necessary either to break lines, for standard-size printing, or to print in a much larger format (Books 3 and 4 are already a non-standard format size). Either one of these options would again go against the first ‘given’ of the piece – the meticulous organisation of space (12 [6+6] lines per etude, which again is not respected in Edition Peters’ published score). More importantly, this kind of enlarged score would work counter to the performative energy that the original score imposes on a performer, and thus even if more “accurate” in some way, would in fact work against another important aspect of the work’s musical intention. The only reason for attempting this augmentation throughout the etude was for me to gain a better grasp of the space-time layout of the work and to create coherent relationships. The process of ‘blowing up’ and augmentation also helped in combing through other particularly dense sections and deciphering precisely which characteristics belonged to which pitch, since as Figure 1.2.2.9 demonstrate, the indications cab be hard to disentangle at original size.

Figure 1.2.2.9: Augmentation of the first bar from Etude XVIII

In this way, the mind has the same space-time orientation as in the original score, with the benefit of clarity for practising in this augmented reality, like slow motion. I used enlarged scores as complementary to the original score during the preparation phases. I would always performance from the original score. While I transitioned to using only the original score closer to the first time I performed the piece, to help strengthen the visual familiarity and comfort, I would on occasions still go back to the enlarged version for practicing a specific detail.

It remains challenging to execute all the events even after all these processes of practising have helped gain a more coherent, even a ‘rhythmical’ understanding of the piece. But the dedication to understanding the proportional relationships between the changes, and their spatial and temporal placement, certainly benefits the accustoming of the body and mind to execution, almost creating a choreography of gestures for the performance.

While making this detailed analysis of the enlarged segments, another possible inconsistency came to my attention. In these segments the main element is the depiction of the pitch, and the additional specifications are meticulous only for the dynamics, and occasional ‘arpeggio’ of the chords (figure 1.2.2.10).

Figure 1.2.2.10: Specifications for arpeggio per ictus in condensed sections of Etude XVIII

Besides this breaking of the chord, additional elements that have been attributed to each note are (figure 1.2.2.11):

Figure 1.2.2.11: Elements and characteristics per ictus in condensed sections of Etude XVIII

From this, it becomes apparent that these condensed segments (A-J) seem to contain far fewer parameters per sound event/note, than the rest of the Etudes. The most detailed from these segments, segment F, has seven agents. Considering that this consists of 21 ictuses, this makes only the third of it has assigned details beyond pitch and dynamics. With the dense determination of each aspect of each note throughout the work, these sections become sparsely detailed in comparison.

This raises the question of whether all the compositional steps were followed in these segments, and it just happens that chance process didn’t assign further determinates, or is it rather that in the face of an overwhelming number of notes, some of the ‘rounds’ of chance were evaded.

- [1]Pritchett, ‘The Completion of John Cage’s Freeman Etudes’.

- [2]James Pritchett, John Cage: Freeman Etudes Books One and Two (Irvine Arditti, violin), CD liner notes (Mode Records, mode 32, 1993).

- [3]Email, James Pritchett to the present author, 3 November 2018.

- [4]In this respect, one could think of Emis Theodorakis’s performances of Xenakis’s Evryali.

- [5]Cage, Freeman Etudes, p.1.