5.4 Coda: Memory and Score as a Prompter

Dario Buccino’s Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16 demanded rethinking the process of work and especially rethinking how and what to memorise. This is not an isolated case in respect of challenges to process and memory. Works by John Cage, Evan Johnson, and Miika Hyytiäinen also provoked reflection on the matter of process, memory, and memorisation.

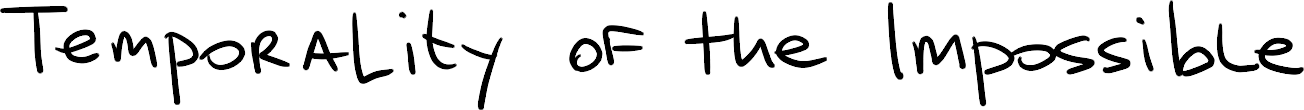

Much like Buccino’s piece, Miika Hyytiäinen’s Impossibilities for Violin cannot be practised in advance in its final form. The score for this piece is a two-channel video, which is generated right before the performance and projected for the performer in the moment of the performance, with the audience already present. For the material in the piece, Hyytiäinen uses excerpts from difficult pieces from violin repertoire dating from Biber to present time. In addition to excerpts from music pieces, there are various non-musical materials: text, images, gifs, and mems, and changes of clothing. The performer does not know the final selection of materials that will appear in the moment, nor the order or contextualisation they might have been assigned. The performer discovers the score for the first time, in real-time, together with the audience. The piece unfolds by the performer being besieged by two projection screens each with its own material (figure 5.4.C.1). The material rapidly and independently changes on each screen and the performer must react immediately, without any prior knowledge or practice of the exact sequence of events. While I have played through years almost all of the pieces from the already existing violin repertoire from which excerpts are quoted and used in the piece, some recently but some of them have not been actively on my repertoire for even six or seven years, there would also appear material that was not previously mentioned and represent a complete surprise. What I found particularly valuable and elucidating playing Impossibilities for Violin was the realisation of “movement memory”, a layer of memory within the body that functions almost like reflex when prompted by seeing a specific score excerpt. In rehearsals and try-outs carried out with Hyytiäinen, I realised that in any run of material we did, even with a split second of thinking about which piece the excerpt belongs to, the reaction would be too late. However, leaving the body to react to all the visual aspects of a score (characteristics of Bach’s score, of Cage’s score, and so on), it would not only react in time, but it would also execute the actions taking in consideration the original context of the piece. This piece has opened an extended understanding of the corpus of accumulated embodied knowledge and the corporeal archive each performer builds through their performance practice and career.

Figure 5.4.C.1: Miika Hyytiäinen’s Impossibilities for Violin; stills from the video, available at: https://temporalityoftheimpossible.com/research/Figures_And_Excerpts/coda_C1.html*

While presence of the score in performing Buccino’s Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16 was a distraction, in performing both John Cage’s Freeman Etudes and Evan Johnson’s Wolke über Bäumen the score can be seen as a prompter.[1]

In Cage’s Freeman Etudes, the relationships between text, thought, and execution are part of material present.[2] As elaborated earlier the unpredictability of the outcome here comes due to the fast succession of sound events with quite distant sets of properties. However, in Freeman Etudes, unlike in Buccino’s piece, even when things do not sound out quite as expected (by how possibly it could sound in much slower tempo) the intention of the performer shines through. It is the presence of this intention, combined with as accurate an execution as possible, that is the attainable attitude that has to be learned and adopted during the process. However, it is a straining and mind-challenging process to completely memorise the piece because there is no direct link between its sounding events. The score will be in the moment of the performance in memory, but it is the presence of the score as an object that will trigger the actions.

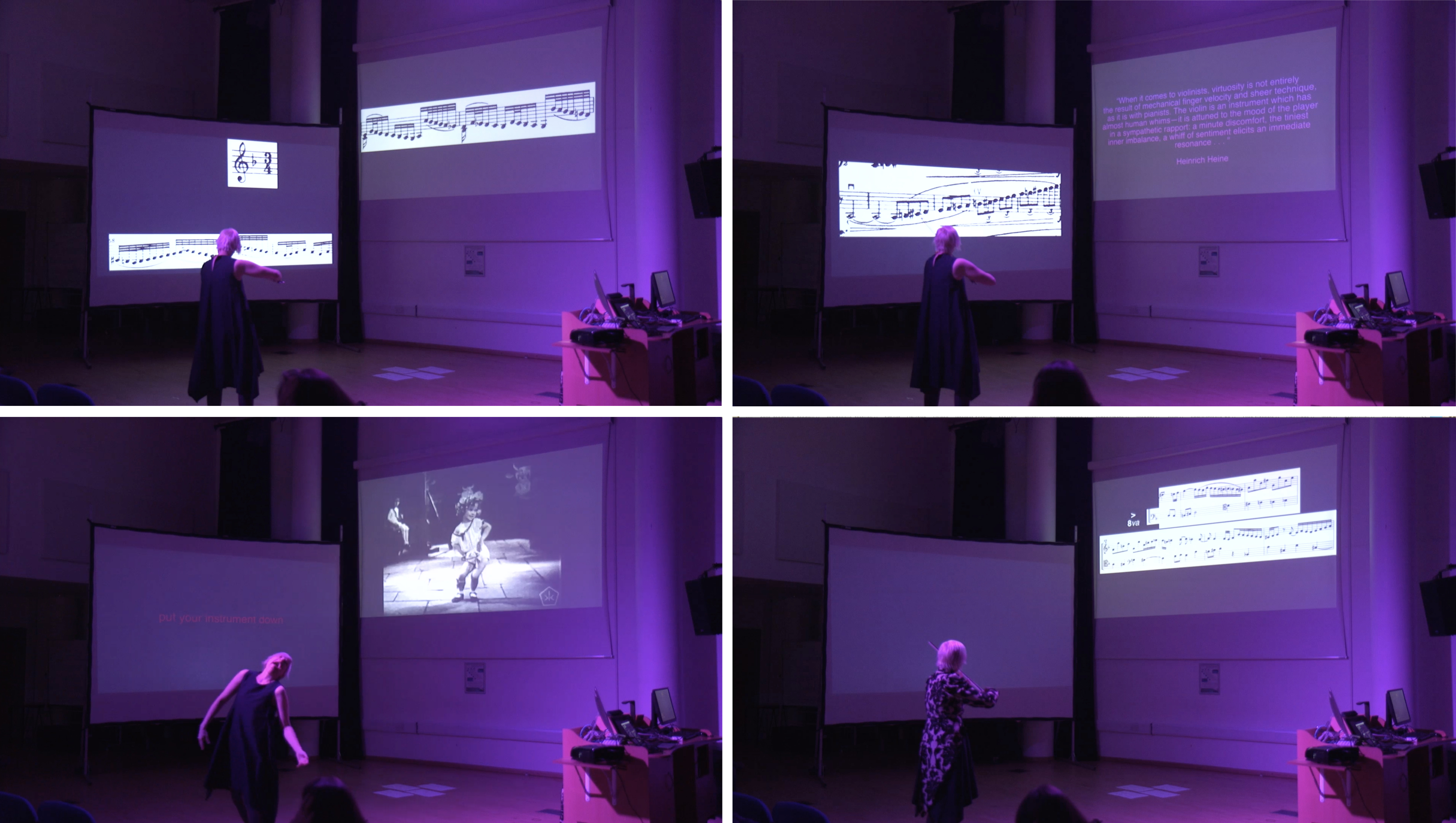

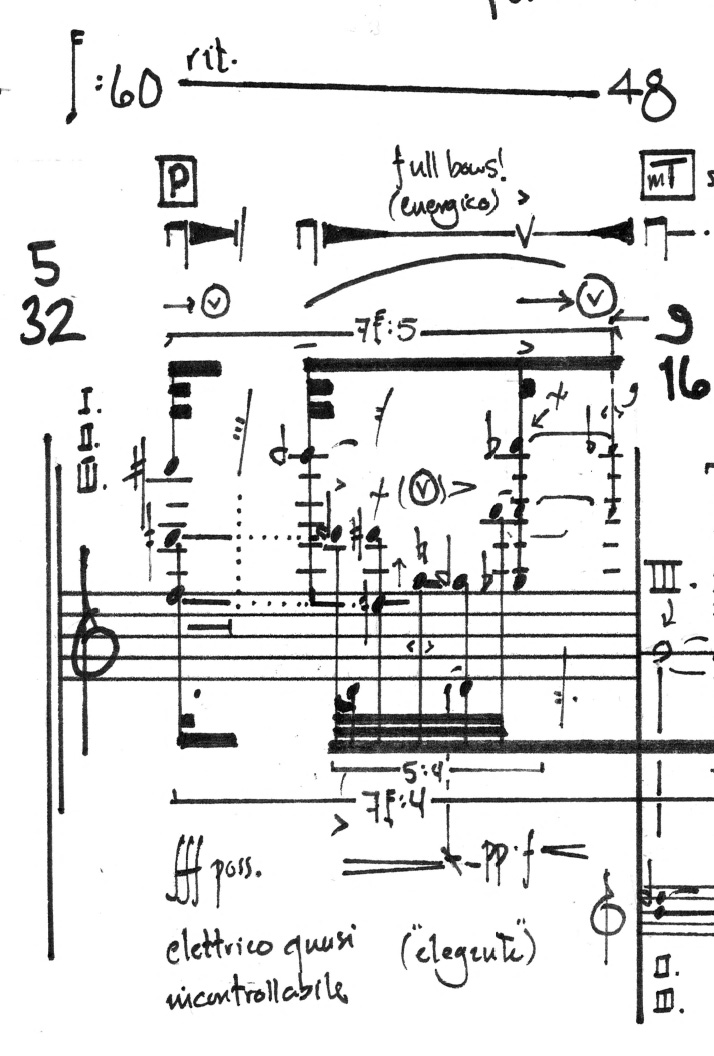

In Wolke über Bäumen, Johnson works with minute detail, sometimes superposing almost opposing articulations and musical character. There is a linearity and even two quite discernible lines, one of frantic character (figure 5.4.C.2) and one of calm character (figure 5.4.C.3). The challenge for processing and memorising this work mostly comes from one crucial aspect used as musical material: tuning the violin during the piece. Turning the peg in small increments is an action that has an element of surprise: the peg can move more or less than expected. When moving the pegs to adjust the tuning of gut strings while playing at the same time, there is a high probability that these actions will always produce a different outcome in pitch and timbre. This has a destabilising effect on how the piece is retained, as it has a high probability to sound different in each peformance. The tuning and complexity of rhythm and techniques all amount to a high potential of disorientation.

Figure 5.4.C.2: Excerpt from Evan Johnson’s Wolke über Bäumen, from page 1

Figure 5.4.C.3: Excerpt from Evan Johnson’s Wolke über Bäumen, from page 1 and 2

In the working process, I found it helpful to separate thinking about sound qualities that come as a result of the right-hand actions and the sound characteristics (pitch) related to the left-hand actions. The piece is notated at fingered pitch, but with the tuning at the beginning and change of tuning during the piece, it will never sound as written.[3] My approach was to firstly work in a way that would help in blurring the expectations of pitch that come as a result from the placement of the finger on the fingerboard, while still keeping the mapping relationship between the fingerboard and the hand.

The first phase of the process was to isolate the more densely written material (as example in figure 5.4.C.2) into motive-like units. Each figure was then practised for its rhythmical structure in regular tuning, to establish the initial mapping of the instrument. In order to train my mind and ear to not anticipate music based on the sounding pitch that comes from the place the finger is placed on the fingerboard, but still to retain the mapping of the violin, I would practise:

- a) with earplugs, thus enhancing the focus on hand movements and touch, and their relationship with the fingerboard

- b) in random tuning so as to strengthen the location of the finger separated from the pitch. I used the random tuning as a way to anticipate unpredictable string tuning that could occur during the performance as a result of possible non-responsiveness or unplanned unwinding of the peg.

Throughout all these exercises, a goal was to consciously focus and expand the inner feeling of the hands trajectory and distances travelled. Additionally, I would consciously focus on creating better visual mapping from the player’s point of view. I would also use a mirror for external control, as well as consulting video recordings of myself without sound. I applied the same processes of work to the material with the extended slow-moving character, shown in figure 5.4.C.3. In this slow-changing character, the glissando has horizontal and vertical gestures. Horizontal gestures are the trajectory the left hand must make from point A to point B and the vertical moment is the change of finger-pressure. The vertical movement has been discussed in more detail in chapter 4.1, as I found this aspect of the movement to be more related to the sonification and timbre of the sound. However, I worked on the horizontal movement in the above-mentioned principles not only for retaining the mapping of the fingerboard separated from pitch, but also focusing on tactile reactions between the string and the fingertips and then listening to minute changes in sound.

Exercises that were intended to strengthen the disconnection of left-hand actions from pitch expectation were firstly practised with regular bow pressures. I would dedicate the next phase of work to pursuit of appropriate sonic identities and interpretation, through combining the layers and details of right- and left-hand actions. I found that, for my performance practice, through these processes of work each of these elements of the piece becomes embodied and will be in memory, but in the moment of performance the presence of the score acts as a prompter and enables details and intentions to come out in more detail and nuance.

- [1]This could be said also for many other pieces of complex character, and especially from the so called new-complexity genre.

- [2]For more detailed discussion on the relation between text, thought and execution in Cage see Chapter 1.2 [Please see full Thesis, available via University of Huddersfield's repository.]

- [3]Johnson, Wolke über Bäumen, Performance Notes, p. ii.