5.2 Memory

In the perpetual process and situation of everything in between, ‘without any fixity to hold on to, with no common grounds’,[1] in Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16 memory and memorisation also became a challenge. If there is no fixed form and everything is equally important, everything must be memorised without any order, but with the ability to create orders when triggered by the HN system.

The realisation that the form is a potential of becoming, and not one fixed iteration that must be learned, had at first a destabilising effect on my confidence in how to actually perform this work. However, through the processes of dealing with the material I established through working on the piece, I clarified that this in-between state created by non-fixities must be understood in fact as an armature that will hold and carry through all these unexpected aspects of the piece. Furthermore, this understanding brought the realisation that Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16 is like a maze. However, I cannot memorise one path through the maze, because there are multiple paths to take; I have to memorise the maze. Thinking about the piece with this approach brought back the needed confidence for performing the piece.

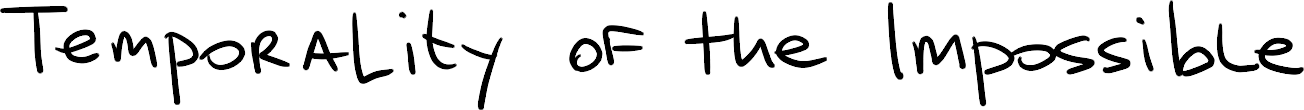

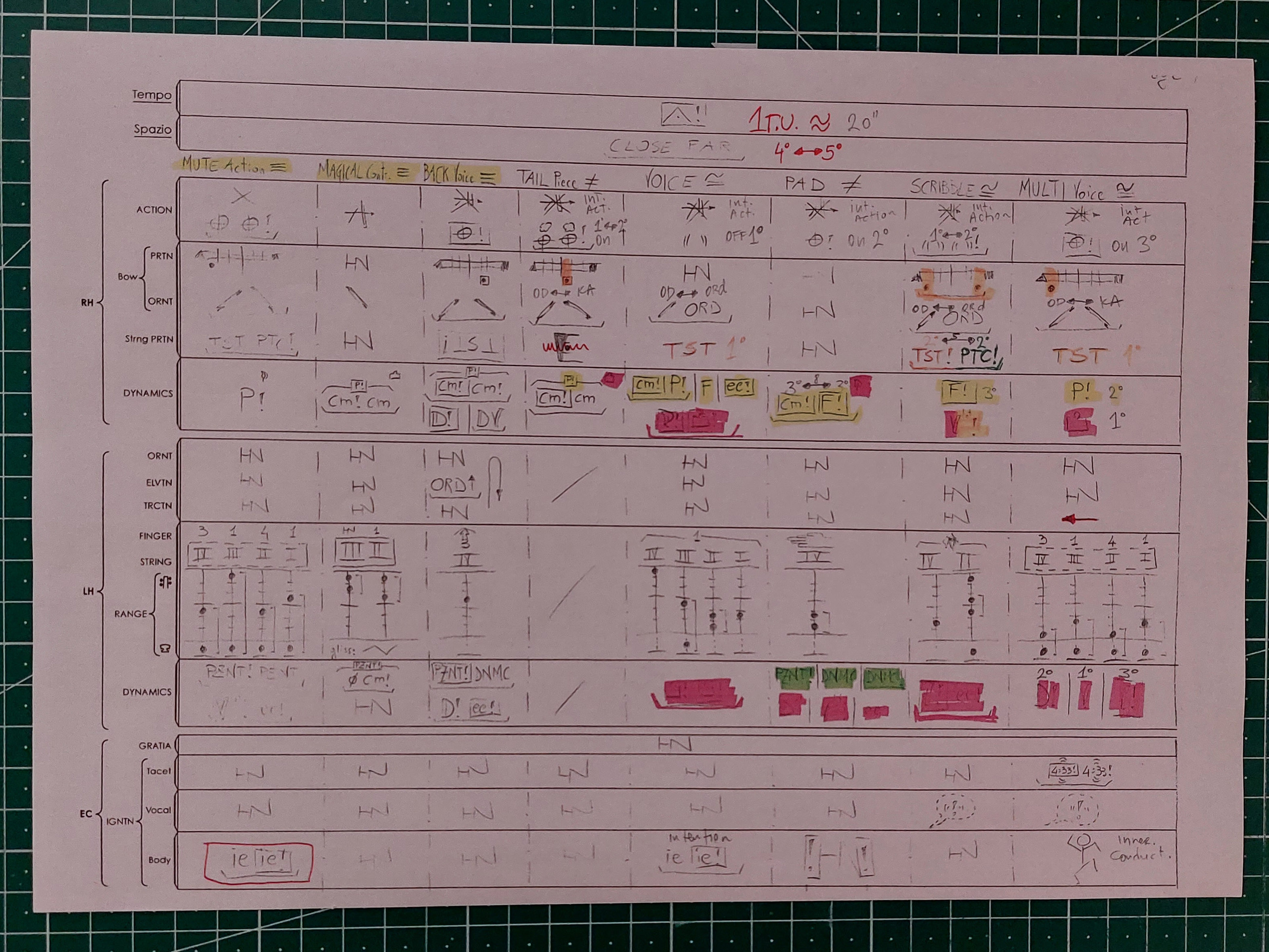

Because of its organic flow, hearing and seeing one performance of the piece does not fully portray the extent of this superabundant web of possibilities nor why “memorisation” is a challenge. The following examples show a fraction of the potentials, by examining combinations that arise from only three identities of one page. The examples in figures 5.2.1. to 5.2.3. work with MAGICAL Contribution, Voice, and Scribble from page 9.

Figure 5.2.1. Exploring potentials of Form and Sounding in Dario Buccino's Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, on three identities of page 9 – example 1

Figure 5.2.2. Exploring potentials of Form and Sounding in Dario Buccino's Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, on three identities of page 9 – example 2

Figure 5.2.3. Exploring potentials of Form and Sounding in Dario Buccino's Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, on three identities of page 9 – example 3

As can be seen in the videos, in example 1 (figure 5.2.1) the order of sub-bars/identities is MAGICAL Contribution, Voice, and Scribble, in example 2 (figure 5.2.2) SCRIBBLE, Voice, and MAGICAL Contribution, and in example 3(figure 5.2.3) Voice, SCRIBBLE, and MAGICAL Contribution. Besides the different order of identities, the parameters used in place of HN were also different:

Although these examples truthfully demonstrate the potentials and the challenges at hand, they must also be regarded as misrepresentations. The recordings were made on the first attempt, without prior practising, but the orders of identities and all HN parameters were determined explicitly and in advance. In performance, it is the ‘hic and nunc’, the organic flow of the here and now that guides when and how material follows each other. This “unknowing” multiplies the difficulty of memorisation. It would not be impossible to think that a performer could, during the process of practice, decide and memorise a structure that can be repeated from one performance to another, but this approach would not do justice for the intention of the piece. Buccino often says that the only way to play his music correctly is to play it incorrectly.[2] However, any pre-fixed final structure is in case of HN-composition the highest level of untruthful interpretation, and that is the incorrect way of playing incorrectly. What Buccino means is that the content in the score is the starting point. For it to sound correctly incorrect the performer must go beyond everything that is written by using everything that is there as well as everything that is not there but that is contained in the HN. The angst of unknowing but trusting to find is one of the driving energies which allows the HN system to enter the equation of chance performance.

Buccino does not specifically insist that his HN-based works are performed from memory, however the context of the piece strongly implies it. In fact, it needs it, as I will demonstrate through the experience of the premiere performance in the later part of the text.

In a piece of music in which there is only a conceptual melos, which itself is a forever present-melody ‘in a continuum of apprehension continua’,[3] where there is never nor could there be a retained melody that can act as a ‘re-presented melody’,[4] I had to reexamine what and how I retain the specificities of the score and channel their appearance ‘in a now’ and ‘all at once’ of perceivable ‘temporally extended content–the so-called spacious present’.[5] It was also challenging to retain or rely on any sense of sequenced and consistent gestural memory and mimetic memorisation. It is not only that there is no concrete and absolute return of sounding that is linked to a specific gesture, but there is also no fixed, choreographic trajectory between gestures themselves. The gesture itself is not linked to a fixed pitch; the energy and origins of a gesture can mutate, so it is also difficult to rely on mapping out the instrument (and here I mean both my body and my violin as individual instruments, and my body and violin as one combined whole). Furthermore, in a score with this amount of surplus of information, which is simultaneously fixed and not fixed, even “chunking” – a ‘relationship between continuity and discontinuity in our minds’ – becomes insufficient as a tool for comprehension since, in practice, when performed this piece relies on intentional, continuous, and unplanned discontinuation of material.[6]

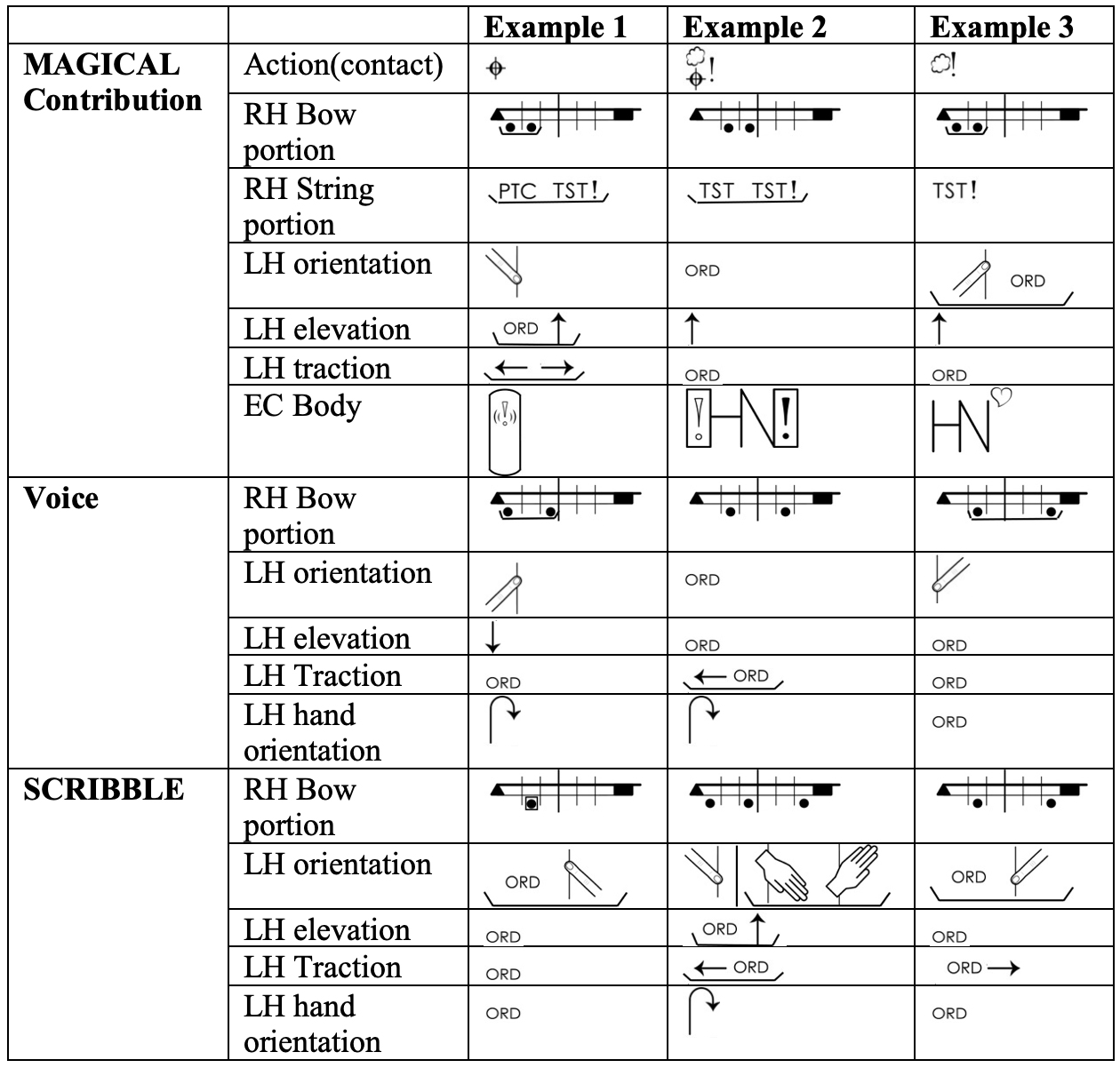

As described in chapter 2.1.1, one page is considered equal to one bar. The bar is subdivided in eight sub-bars, each being an idiosyncratic identity. The order of sub-bars/identities on the page is always the same: MUTE Action, MAGICAL Contribution, BACK Voice, TAIL, Voice, PAD, Scribble, and MULTI Voice. Further to this, the four sub-bars/identities of the left side of the page/bar belong to the introvert aesthetics and the four sub-bars on the right side to the extrovert (figure 5.2.4). Buccino’s instructions state that the execution of identities does not and should not be performed in reading left to right (or right to left), but this order should be governed by the hic et nunc. The consistency in representation on the page that Buccino has proven to be beneficial in memorisation of the piece.

Figure 5.2.4: Overview of Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16 on the example of the first page

The solution I found, after the process of learning the language and symbols, was to employ photographic memory as a method to retain the score. The process of training photographic memorisation consisted of three main stages:

- ■ Memorisation of each identity per page and the page as a whole

- ■ Working with a page as a whole and memorisation of pages in order

- ■ Refreshers.

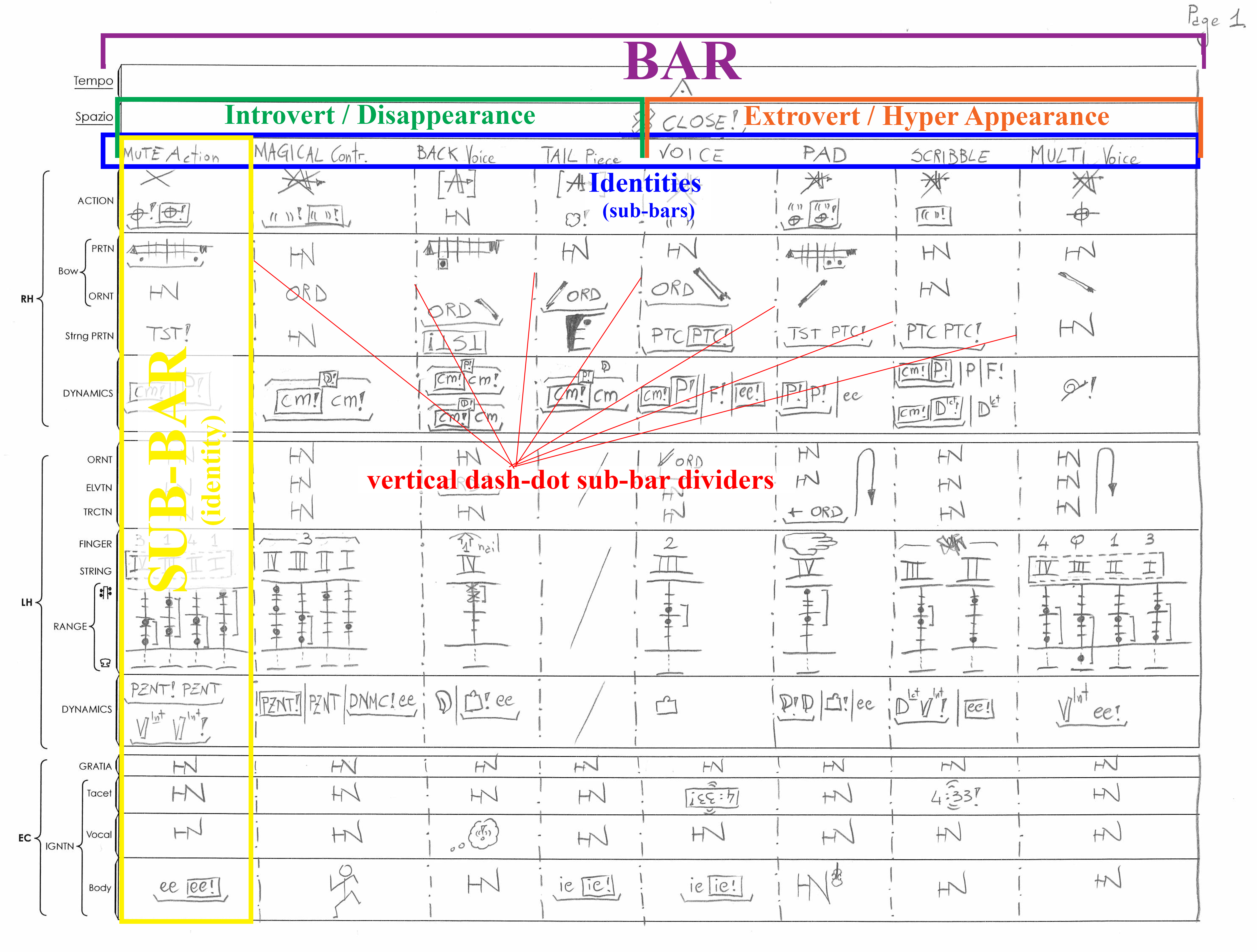

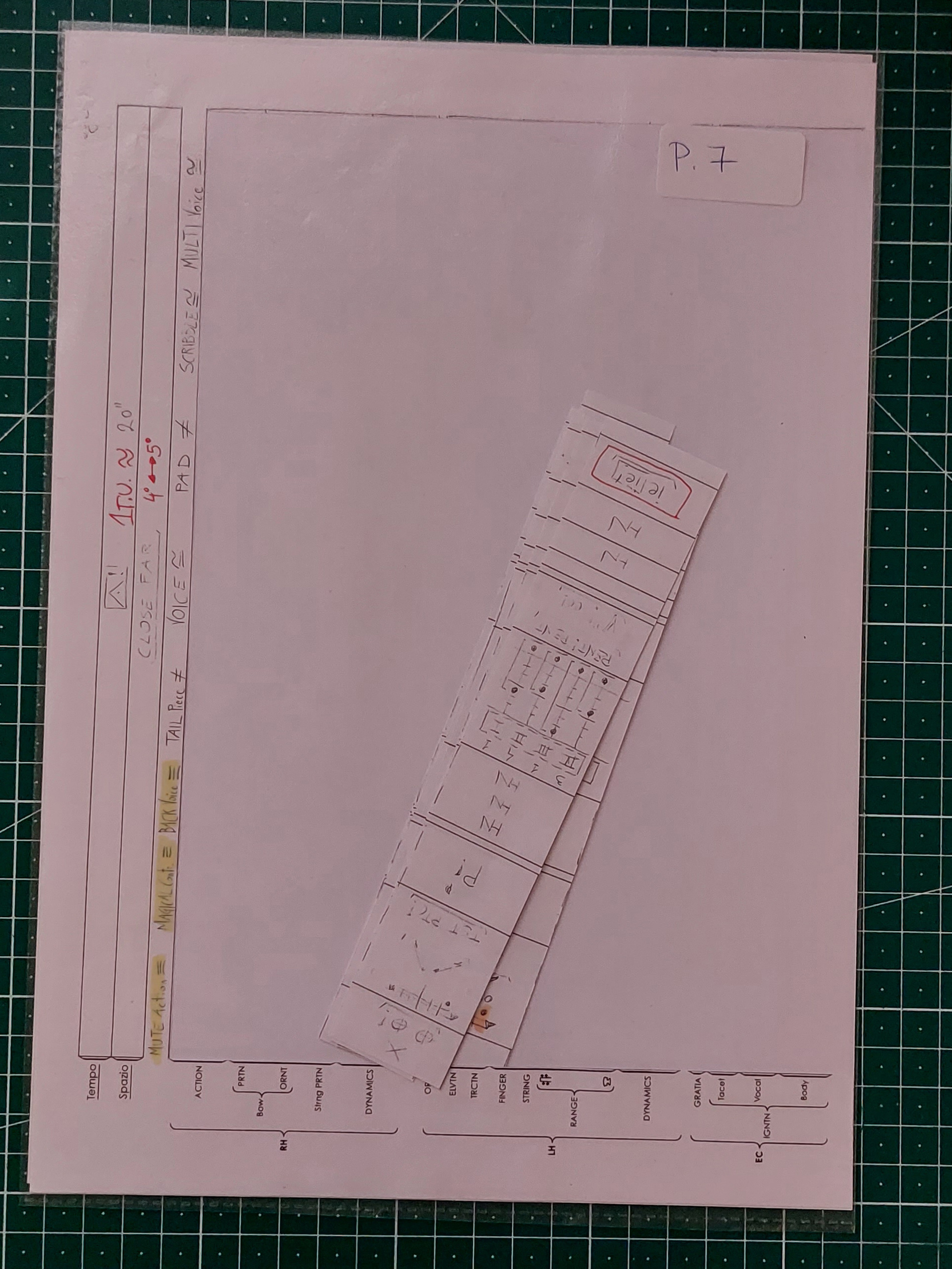

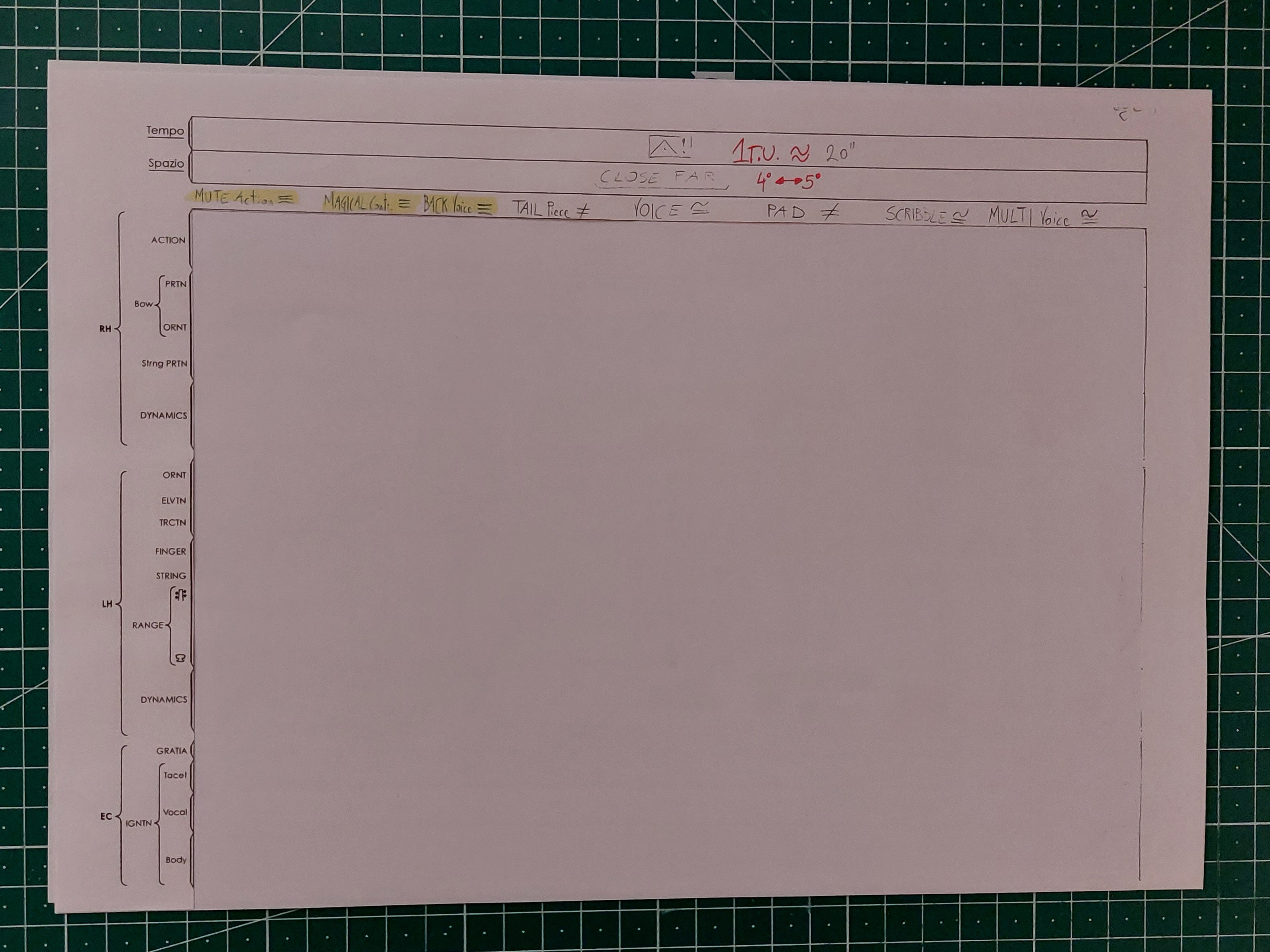

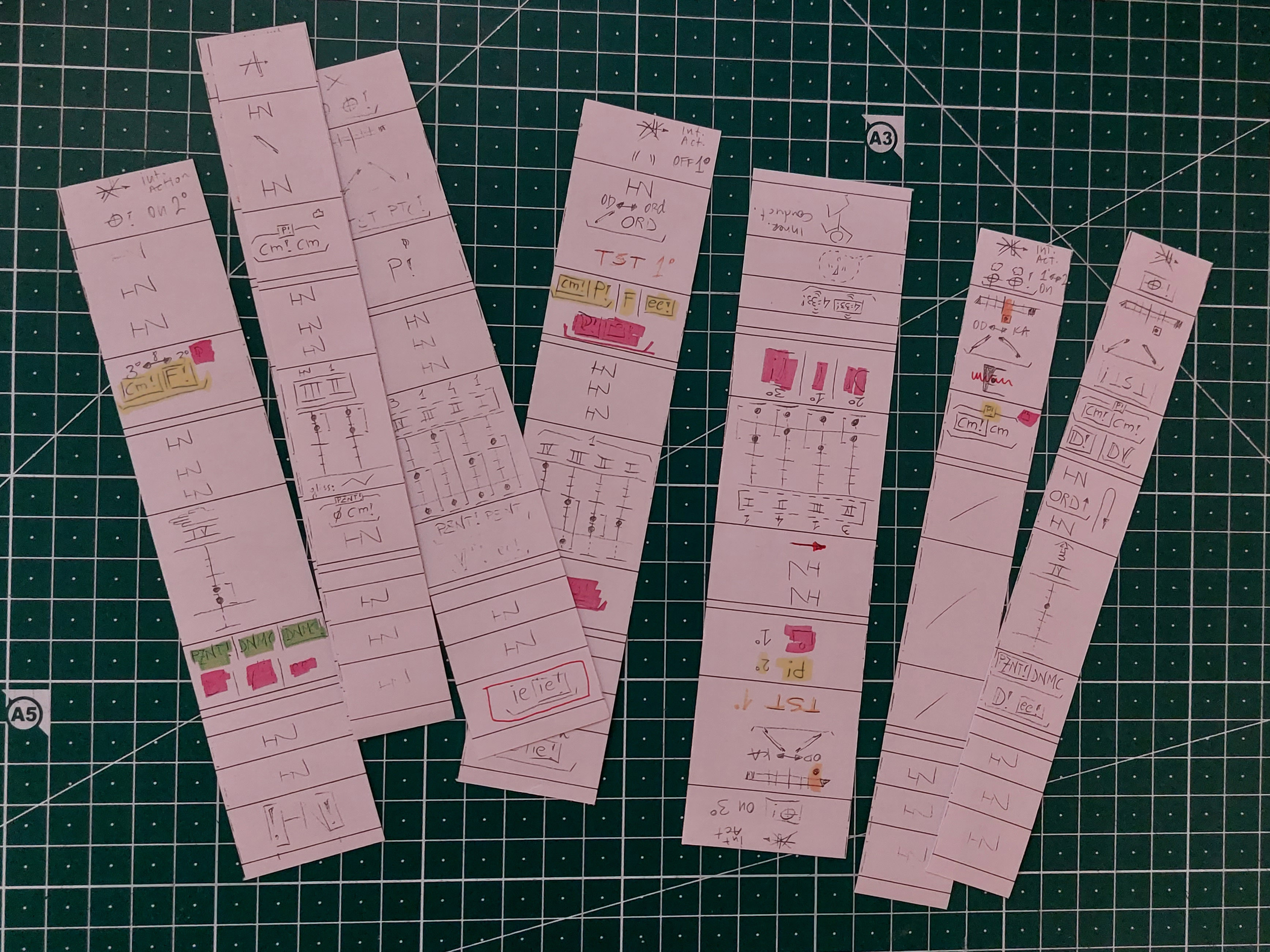

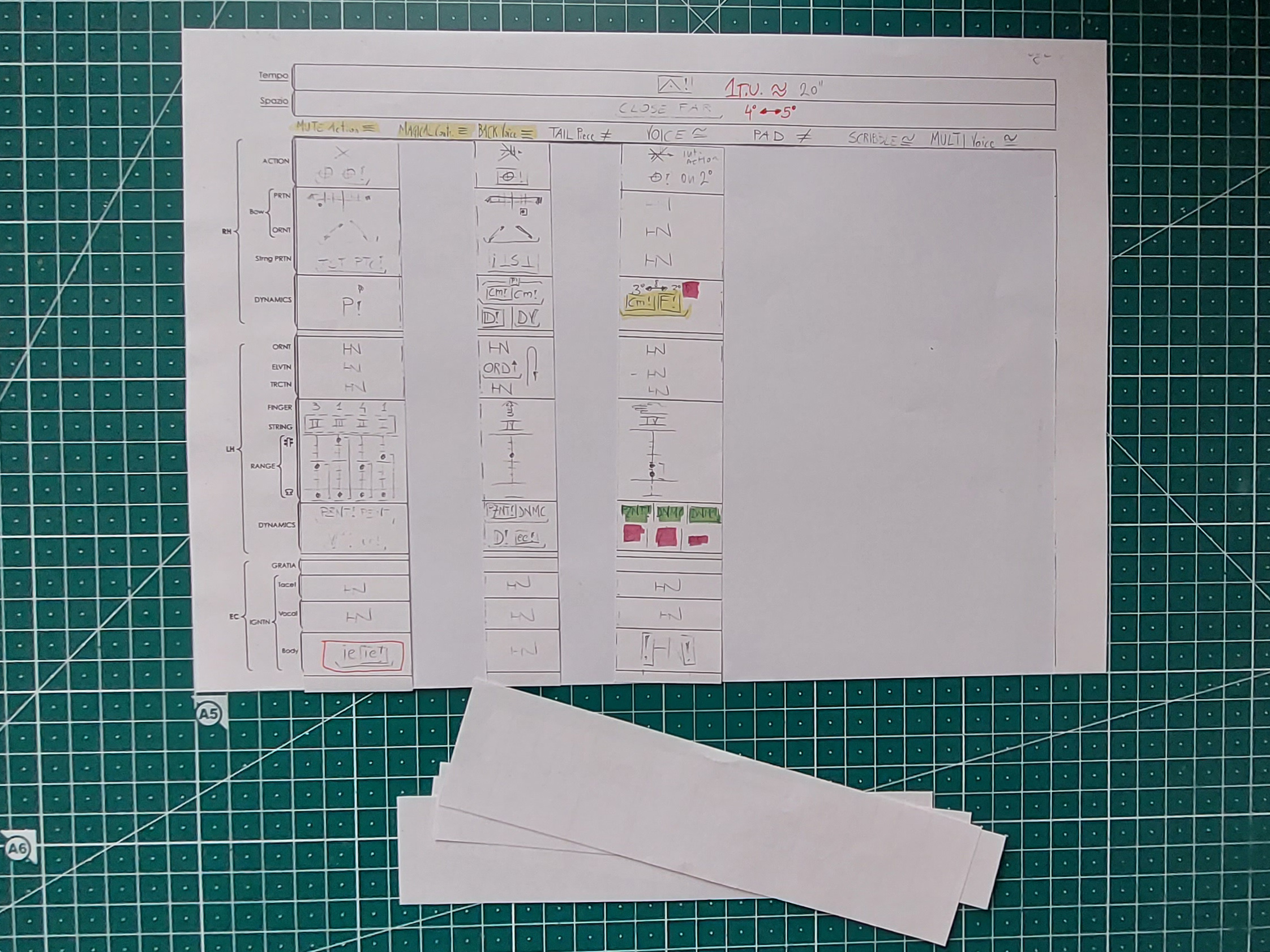

The first two segments were carried out by creation of a memory game, each with its own set of cards. First, each identity is memorised on a page. The memory card set for this segment of work consists of one control card, which is the actual page, the placing-map, and the training cards. The training cards are the cut-outs of each sub-bar/identity column, but the name of the column is left out. The section of the page which contained the frame with identity names became the placing-map. Initially, I thought that I would need two sets of sub-bar/identity cards for a mini-matching game to help memorise each sub-bar. However, isolating each sub-bar brought further clarity on how clear and individual each identity is. The final set (figure 5.2.5) for this first phase thus included the control card (figure 5.2.6), a placing-map (figure 5.2.7), and only one set of cut-outs (figure 5.2.8). The control card would be facing down or be out of sight. I would set the placing-map in front of me and mix and place facing down the sub-bar/identity cards. Drawing one at a time, the goal was to achieve as fast a recognition as possible upon flipping the card and then placing it on the map, in its correct slot (figure 5.2.9). Only after all identities were placed, the control card would be turned for verification.

Figure 5.2.5: Memorisation package: a plastic folder (with page number written on it) containing the control card (under), the placing-map, sub-bar identity column cut-outs; on example of page 7

Figure 5.2.6: Example of page 7, control card

Figure 5.2.7: Example of page 7, placing-map

Figure 5.2.8: Example of page 7, sub-bar/identity cut-outs

Figure 5.2.9: Example of page 7, placing sub-bar/identities columns on the placing-map

After working with this process for each of the 12 pages, I moved on to working with whole-page cards and memorisation of pages in order. The working set for this stage included 24 cards, each page with a double, with dimensions approximately 15x11cm. Page numbers were removed from the top right corner of each set of cards; they were kept in envelopes, featuring a “control” page with the number (figure 5.2.10).

Figure 5.2.10: Memorisation card set

I would start this segment of memorisation by working with only two randomly selected pages at a time. Then the number of pages per turn grew until all 12 pages would be in play. In the first part of this process, in working with two and up to ten pages, the order of pages was random. I would first place the selected cards facing up (figure 5.2.11.a) and observe them, and then proceed to flip them to face down (figure 5.2.11.b). The playing set of cards would be mixed and then cards would be drawn and placed on top of its match (figure 5.2.12).

Figure 5.2.11: Memorisation setup: left (a): 4-page round, observation; right (b): 4-page round

In the final stage, using all pages, all control cards were facing down from the start, and they were placed in correct order. From a mixed stack of playing cards, one card at a time was drawn and placed on its match. The goal was to recognise the page in the shortest possible time and place the cards correctly in order. Control is done by flipping the control cards after all the playing cards have been arranged.

Figure 5.2.12: Matching

The last segment of memorisation, “refresher”, is a recurring segment. “Refreshers of memory” entail going through the last memory-game cycle leading to the day of the performance, followed by a final page by page run-through (reading from my original score) before the performance begins. When possible, I would also place the score in a circle, as it appeared to set the mood of spheric dispersion of the time-space setting that is used in the performance (figure 5.2.13).

Figure 5.2.13: Pre-performance review of the score

Left: at Unerhörte Musik, 24 May 2022 (Berlin, Germany), photograph by Dario Buccino Right: at Prima Vera Contemporanea, 2 April 2022 (Palermo, Italy), photograph by author

At this point it is unclear what effect time will have on the memory: whether a pause in engagement with the piece would cause significant loss of information and material,[7] or whether the distance would have a more strengthening effect because of the specificity of the work and long, continuous, and intense working period spent with it. It is, however, certain that this memorisation process has opened a different way of learning and navigating densely written musical material. I cannot recite or sing the identity of a page in the way that I would be able with a difficult piece of a more common notation, learned through a more common process, but once the image of a page is in my head, I know that I know the piece.

Buccino remarked in our various conversations and in his public talks about the fact that there is often a two- or three-year period of preparation before performances of his pieces occur. In the case of Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, I had two months and a week to internalise and then “forget” about the score; to surpass it and perform the piece in the way Buccino intendeds HN pieces to come in the moment of the performance. Although the premiere of the piece went well as a whole, the shortness of time between receiving the piece and the performance can certainly be observed in post-premiere performance analysis. Two main elements that I identify as contributors to this observation are the fear of letting go of the score and the fear of “unknowing” the beginning.

The fear of not knowing how the piece is even going to start became apparent the more the day of the premier was closing in. Out of a desire to portray and present this piece with the justice and gravity I knew it deserves, I have naively fallen to a thought that it could be good to plan out at least some sort of back-up structure on how to begin once I am on stage. This back-up, which was there in case nothing came on its own, disabled me to let go to the moment and start with whatever material of the first page felt right; I was not truly in the here and now. The mind subconsciously went to one of the back-up ideas.

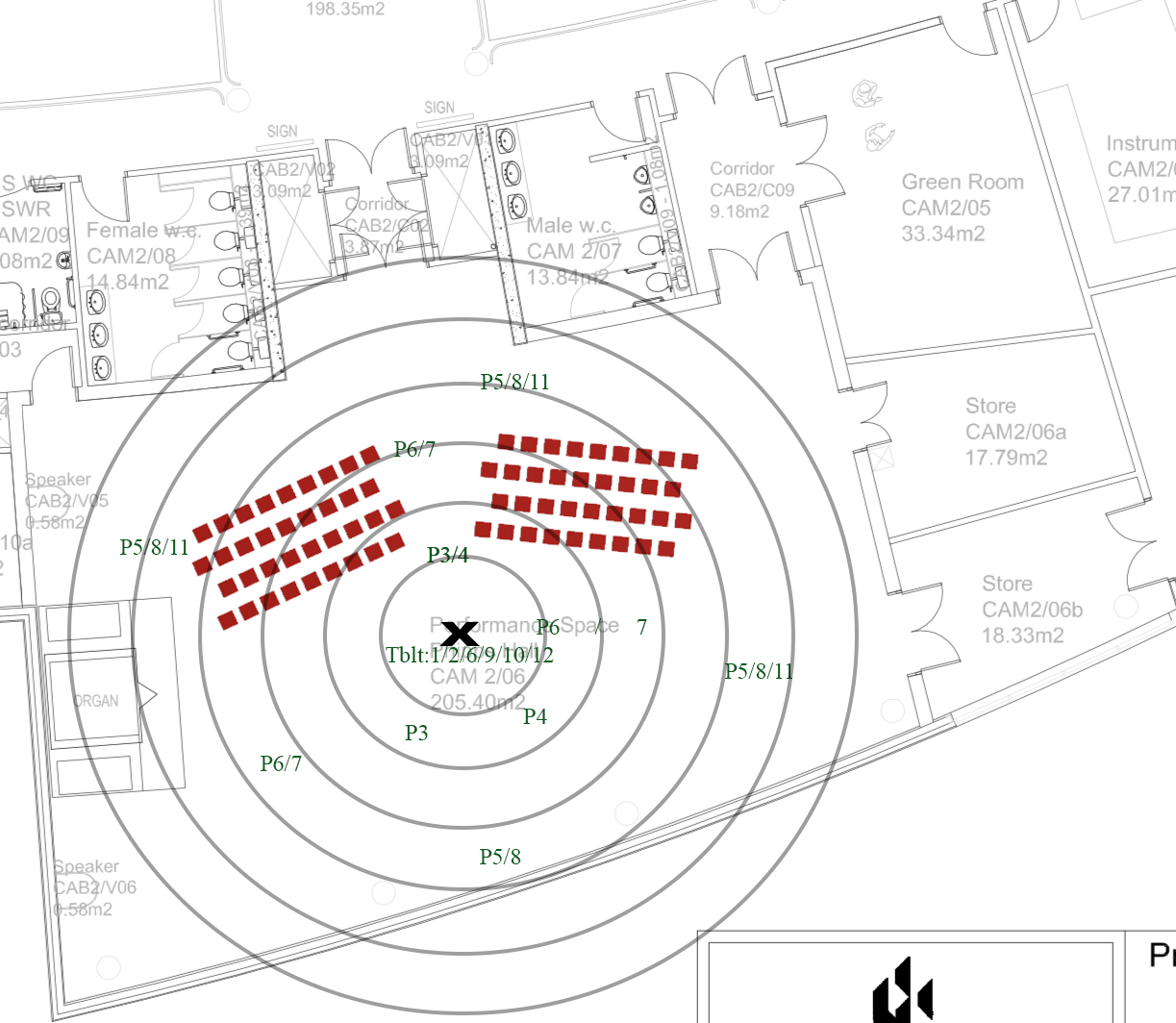

The fear of letting go of the score comes from the abundance of information it holds and the fact that all information must be always held at an equal state of alertness. In conversations leading up to the premiere, Buccino re-confirmed that the piece does not have to be played from memory and that the score can be present, as it almost always is in performances of his music. My main concern was that although dispersing sheets of the score around the space can be seen as an element of scenography added to the performance, it has a counter effect on the organic movement in the space guided by the HN. To lessen this boundary, my solution was to spread multiple copies of the same page in various directions of the space, and in accordance with the Spazio indications (figure 5.2.14).

Figure 5.2.14: Diagram of the space and score placement

The idea was that this would allow me to “stumble” upon the right page in whichever direction I would move during the performance. However, even with this, once the performance started, I felt stuck and unable to be in the here and now. With the physical presence of the score, even if there only as a backup, it became apparent that the mind was automatically trying to find it, cling to it, and focus on the determinate, non-HN, elements present in it – therefore suddenly enacting hierarchy. There was no natural and organic flow. This internal struggle, which was not the conversation and engagement with HN but a real personal struggle that practically isolated me from my own performance, lasted for some minutes into the performance. Feeling that things were not going well, with strength innate through all the work invested, I finally let go and plunged to see what will happen. Buccino was not able to be present at the premiere but watching the recording he recognised this moment as a clear, real, beginning of the piece.[8] The “back-up” beginning and having the score present were false safety nets, and they created a reality that was far from genuine, and was extremely disorienting. Letting go of them allowed me to truly step into the piece. The performer in Buccino’s HN compositions in any case does not have the full power of their own decision; it is the conscious decision of letting go before entering the performance space that changes the dynamics, a moment which allows for the hic et nunc to happen. Every subsequent performance I did was done without a score present in the space and without any “back-up” beginning plan.

- [1]Einarsson, ‘Desiring-Machines’, p. 15.

- [2]Dario Buccino has repeated this in every conversation we had, as well as in public talks.

- [3]Edmund Husserl, ‘On The Phenomenology of the Consciousness of Internal Time’, in Collected Works Volume 4, trans. by John Bamett Brough (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1991), p.38.

- [4]Edmund Husserl, p.38.

- [5]Husserl, Edmund, The Phenomenology of Internal Time-Consciousness, ed. by Martin Heidegger, trans. by James S. Churchill, 2nd print edn (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), p.29.

- [6]Rolf Inge Godøy, ‘Coarticulated Gestural-Sonic Objects in Music’, in New Perspectives on Music and Gesture, ed. by Anthony Gritten and Elaine King (New York: Routledge, 2011), p. 68.

- [7]From the first encounter with the piece and during the research period, I have kept the piece actively in the repertoire and performance circulation. Even with the pause in performances during the pandemic period, the work on the piece did not stop.

- [8]The recording of the premier can be seen in Artistic Portfolio, reference: AP3.1.