4.2 Physicality Interpreted as Material in Aaron Cassidy’s The Crutch of Memory

In The Crutch of Memory Aaron Cassidy constructs a piece which brings high levels of minute detail: demands for the left and for the right hand both together and individually. The right-hand actions and techniques all have the potential for clear sonic identity. However, once put in motion, although very precisely and clearly written, the combination of density, pace of flow of events, and the way the left hand is used create a performative situation in which the sounding outcome can vary from one performance to another.

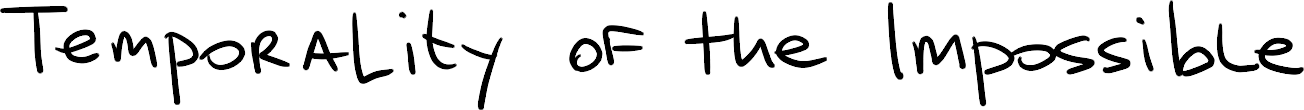

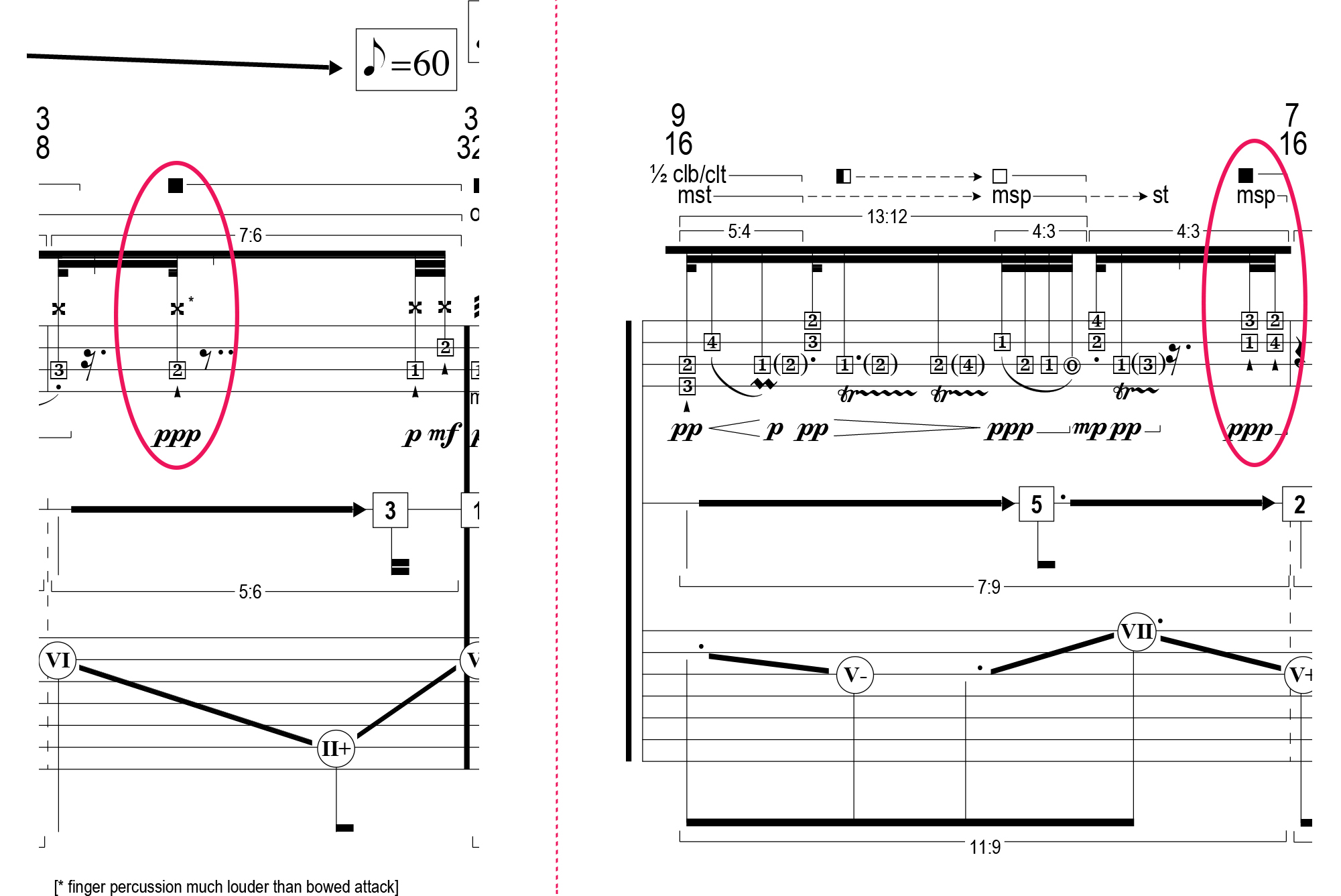

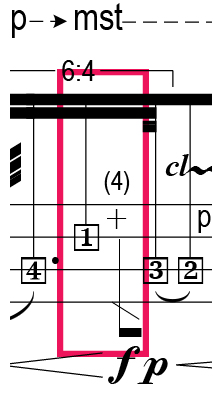

Figure 4.2.1: Excerpt from Aaron Cassidy’s The Crutch of Memory, from page 1, line 2

Cassidy notates the piece using a tablature system, and dividing the material across three staves (figure 4.2.1):

- • the first stave from the top has four lines, each one representing one string (counting the top line of the system as I – E string, II – A string, III – D string, and IV – G string. This section has a double function:

- ◦ fingerings, which denotes which finger should be placed on which string

- ◦ actions of the right hand

- The dynamics are also written under this stave.

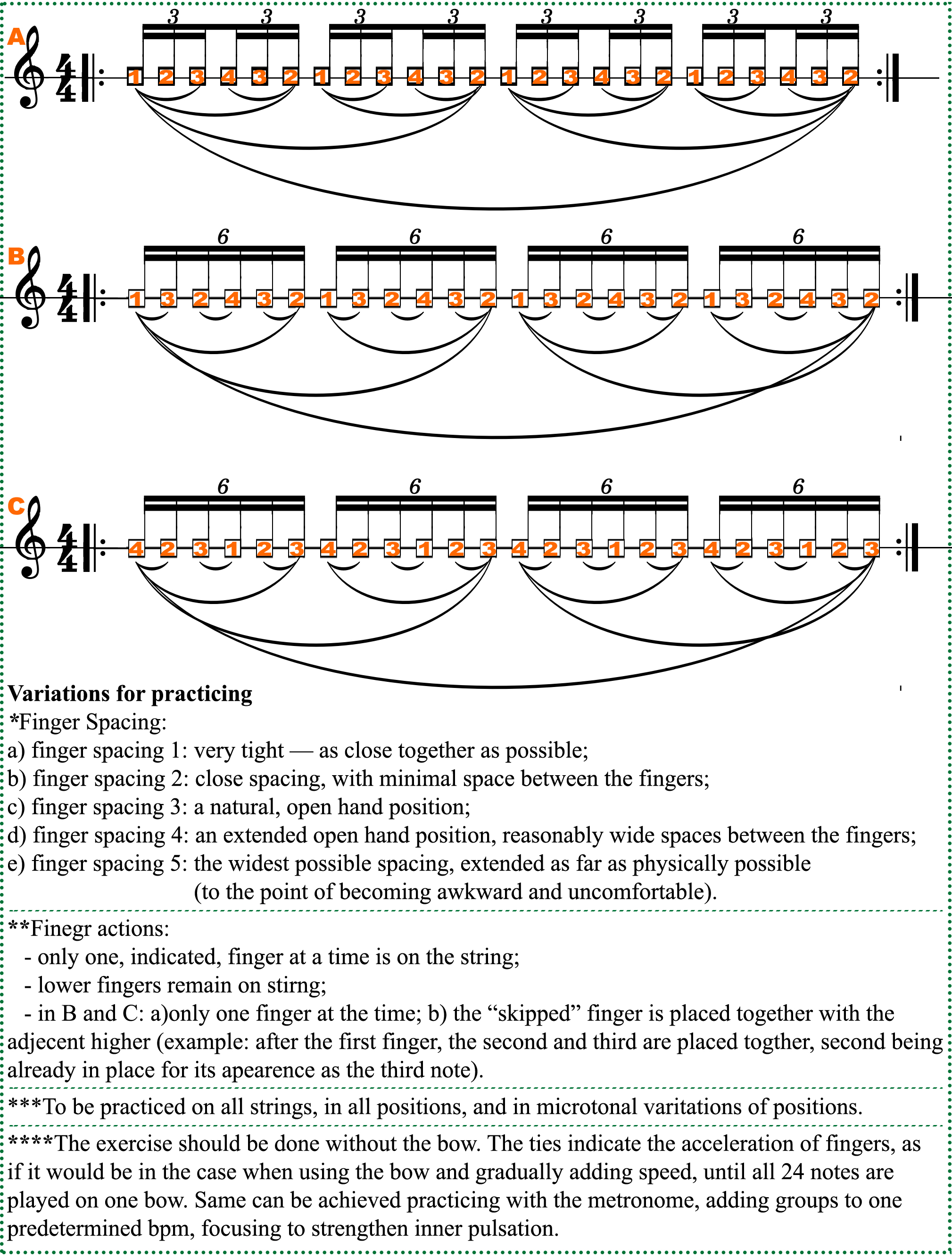

- • the second stave is dedicated to the finger spacing, with a five-degree scale of width:

- ‘1) very tight – as close together as possible

- 2) close spacing, with minimal space between the fingers

- 3) a natural, open hand position

- 4) an extended, open hand position, with reasonably wide spaces between the fingers; and

- 5) the widest possible spacing, extended as far as physically possible (to the point of becoming awkward and uncomfortable). An effort should be made to keep finger spacing widths as consistent and repeatable as possible.’[1]

- • the third stave is a seven-line tablature system, with each line representing one of the seven positions for the left hand, that are to be employed throughout the interpretation. In the performance notes Cassidy writes:

- The lowest staff indicates the movement of the hand up and down the fingerboard. Hand positions are indicated with upper-case Roman numerals and refer to the location of the first finger. The actual locations of the seven positions are at the discretion of the performer, though must remain consistent throughout the work. The most direct options for the locations of these hand positions are a) standard diatonic hand positions, b) positions which are equidistant from one another, or c) an invented scalar system. Position VII should always be at the octave. +/- indications refer to microtonal adjustments above and below the assigned hand position of between a quarter-tone and semitone. Note that arm movement should continue even when strings are not being depressed.[2]

One of the tools I used for disassociating the actions and movements of the hands from one exclusive sounding outcome was to consciously separate and practise each hand’s actions and events individually. The goal was to expand the feeling of confidence in action and gestures themselves and strengthen ability to rely on the body’s knowledge of the acoustic potentials the gesture carries.

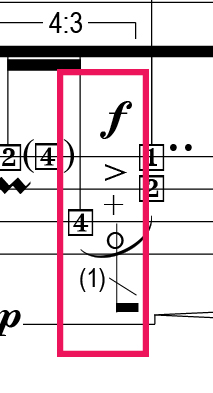

Focusing on just the right-hand actions, with muting the strings with the left hand to eliminate open-string resonating, was the first step needed for detachment from one exact sounding outcome. However, as this kind of string dampening with the left hand also produces a sound of a specific timbre, in order not to link the right-hand action to a specific sounding outcome, I would mute strings in various undetermined holds when exercises were repeated. For each right-hand action-event, I would start by determining which gestures the movement for that specific bowing technique contains and what specific combination of point of contact, pressure, and speed produces the notated articulation and dynamic.[3] I found it especially important to go through the detailed process of examining the gestures within the movement for three specific actions (figure 4.2.2.):

◦ quasi-trillo:  |

|

|---|---|

◦ trillo mordent:  |

|

◦ bow vibrato:  |

and  |

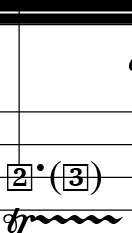

Figure 4.2.2.: Right-hand specialty actions in Aaron Cassidy’s The Crutch of Memory

Both bow-trill actions required finding a right balance and to adjust the bow hold in a way the thumb could rotate the bow between its hair and wood, with the ability to achieve controlling the outcome in a variety of speeds. Bow vibrato required changing back and forth bow pressure or speed during one bow stroke with the goal of creating an audible regular (notated in 32nds note value) or irregular (notated with eighth note value) pulsation in what would otherwise be continuous uninterrupted, “flat” sound. However, this type of work process was not useful only for these more special bowing techniques. In combination with the changes of point of contact during or mid-stroke, detailed dynamic and bow pressure prescriptions, all actions, including detachés, slurs, tremolos, or jetés had to be examined and fine-tuned for each of their event-specific balance of gestures within the movement. Practising in this way allowed me to find the quality of the “tone of the gesture” within the body and maintain each gestural identity not through aural but in-body experience. What I mean by the gestural identity of the sound when it comes to the right-hand actions is a combination of the physical sensation and changes in the body that happen with each specific action which will eventually result in specific sonic shaping of the sound.

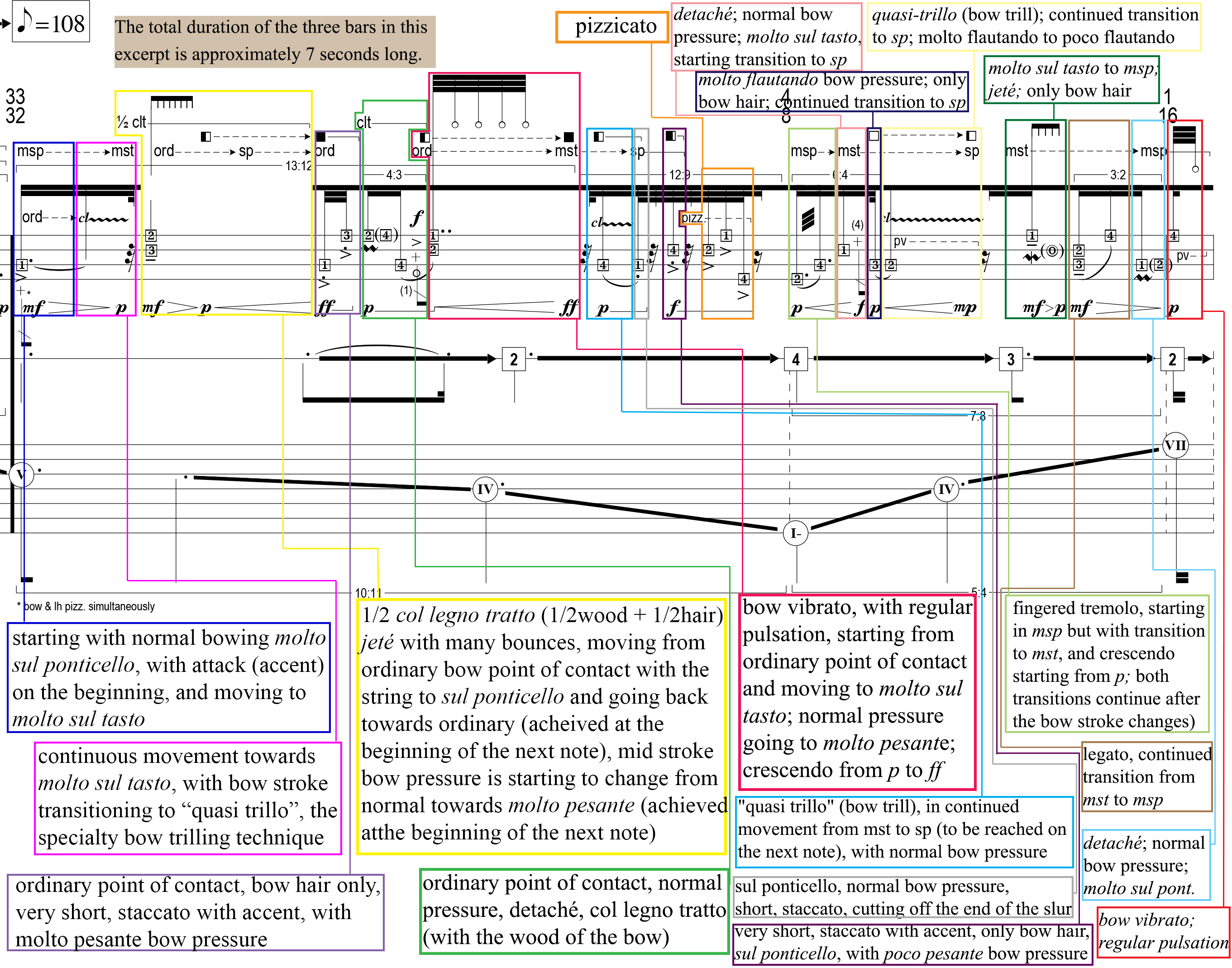

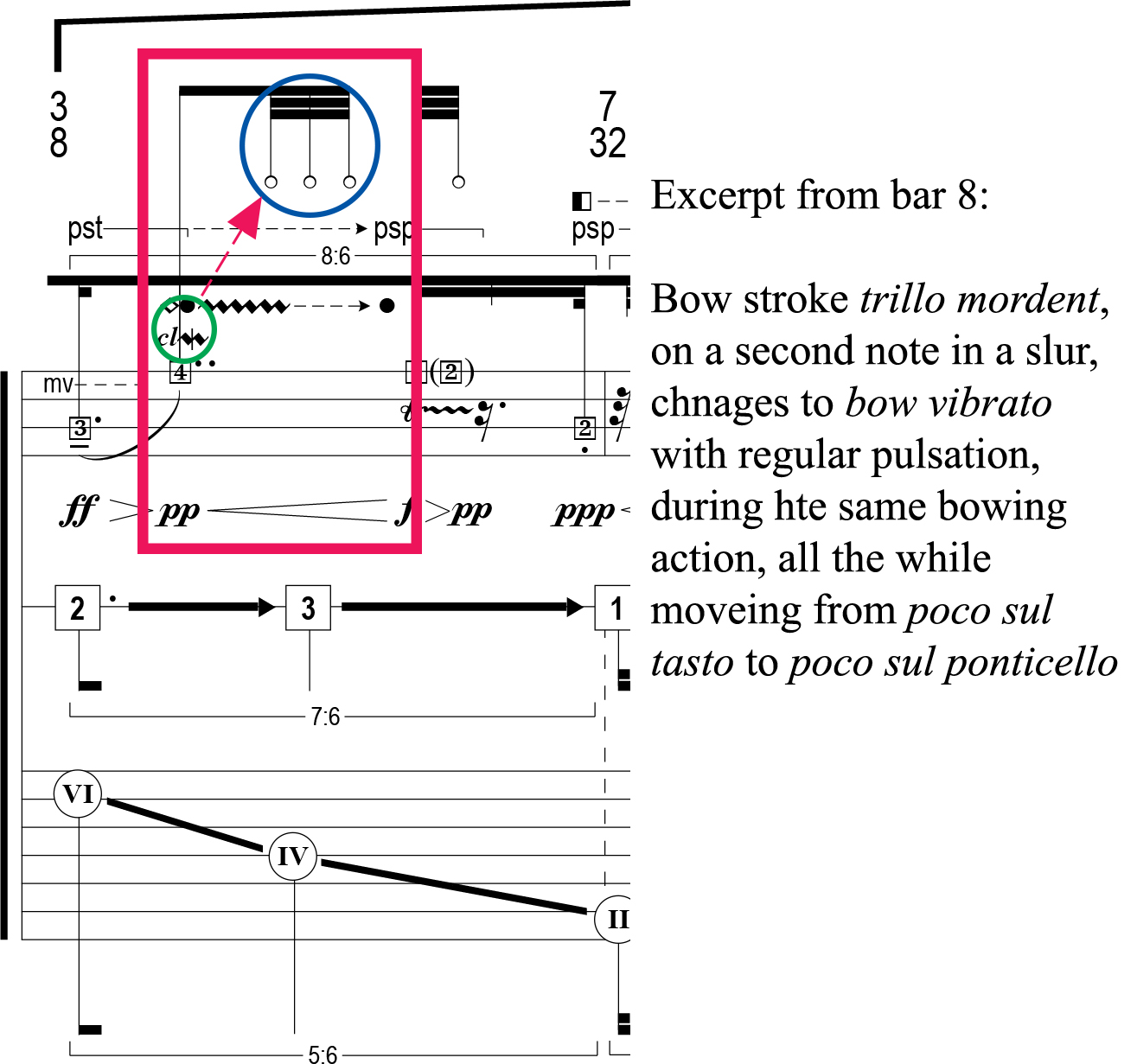

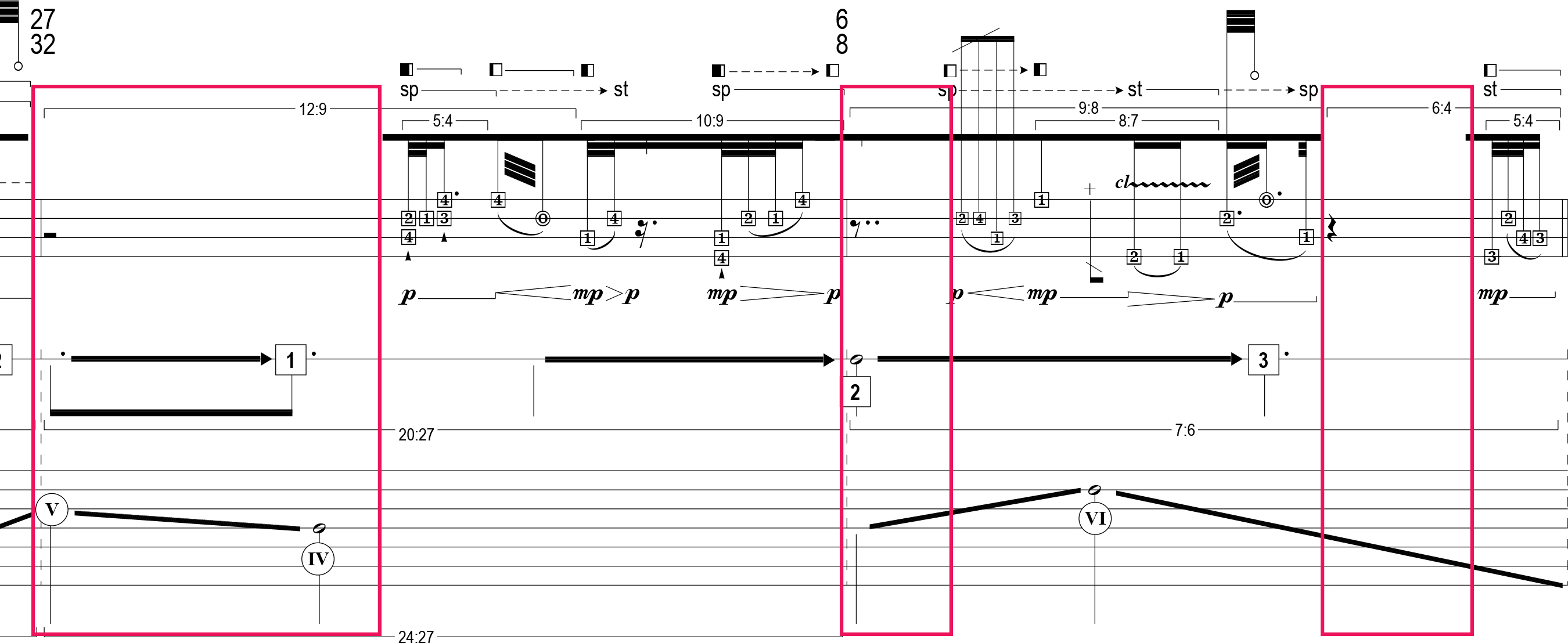

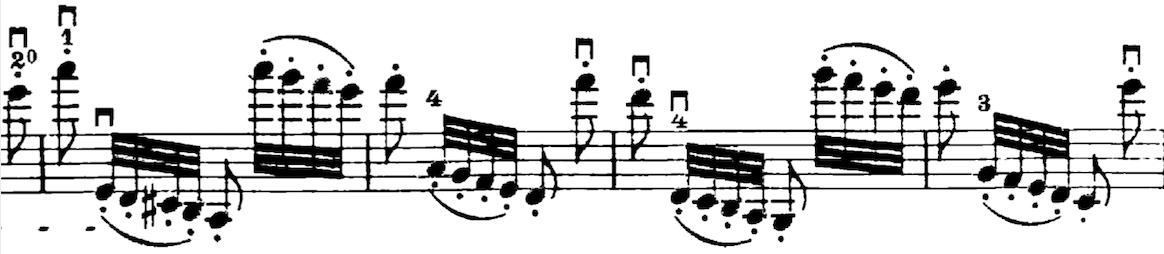

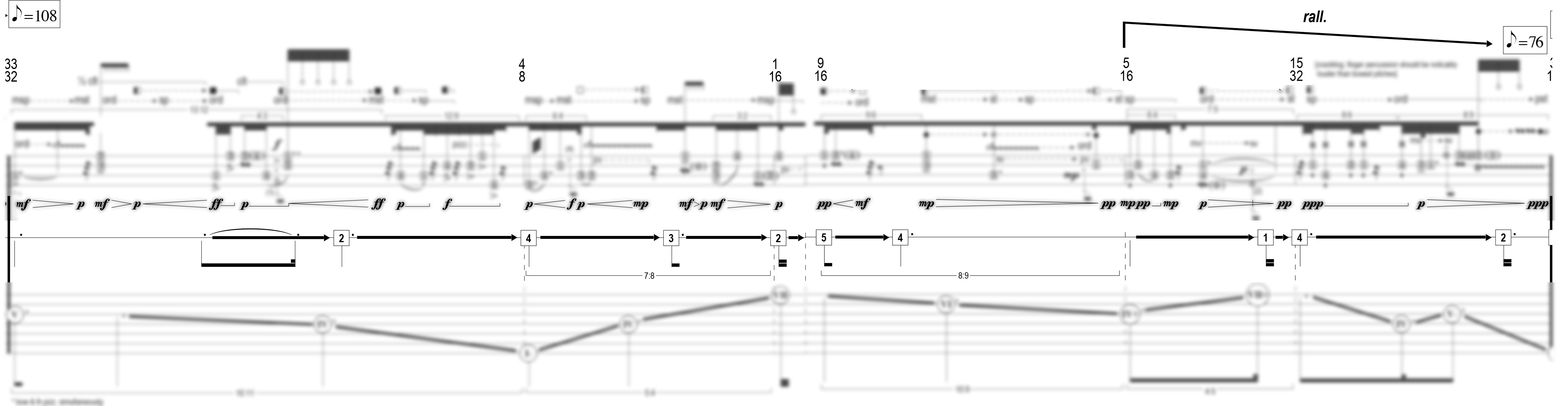

The overall general fast pace of succession and changes of each of right-hand action-events creates a feeling that techniques are often melting into each other (figure 4.2.3). This is not quite the case, as each action must maintain its own clear identity. However, there are instances where different bowing techniques become grouped as one event, as in cases when different bow techniques are being executed on the same held stopped finger and there is no change of bow direction (figure 4.2.4). I found that the approach of practising the actions separately, in all their vitiations, and then slowly building combining each of these events into phrases, to be a useful process that facilitated better overall flow when interpreting the score. Learning this way, through understanding and embodying gestures within the movement in minute detail, also allows for better execution of seemingly contradictory combinations of dynamics and bow pressure, such as for example combining molto pesante (an increased pressure, nearing scratch tone) with ppp dynamics (figure 4.2.5).

Figure 4.2.3: Aaron Cassidy’s The Crutch of Memory – bars 11, 12, and 13; excerpt showing succession and changes of each of the right-hand action-events within a timespan of approximately 7 seconds

Figure 4.2.4: Aaron Cassidy’s The Crutch of Memory – excerpt from bar 8: different bowing techniques merging in one event

Figure 4.2.5: Aaron Cassidy’s The Crutch of Memory – bar 42 (left) and bar 95 (right), examples of seemingly contradictory combinations of bow pressure and dynamics

All the right-hand actions, bowing strokes and techniques, provide a general frame to the sound each time in the same way but, as mentioned, because of how the left hand is used and with the instrument using scordatura tuning, the overall outcome is not guaranteed to sound in one expected same way in each interpretation. In The Crutch of Memory, the left hand is not being linked to a specific pitch. It is in constant gliding movement, applying two separate horizontal parameters of motion:

- ◦ the hand and arm are sliding up or down the fingerboard through seven positions (figure 4.2.1)

- ◦ the continuous change of openness or closeness of the hand: five degrees from very tight to widest possible spacing, as previously described.

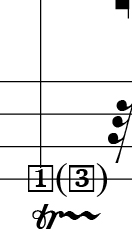

The left-hand movement is to be uninterrupted and continuous even in moments when the right hand is not activated (figure 4.2.6).

Figure 4.2.6: Aaron Cassidy’s The Crutch of Memory – bars 28 and 29, example of continuous movement of the left hand during the pause in the right hand

Another parameter that must be taken in consideration is the vertical motion, the different pressures the fingers have when in contact with the string. There are three degrees for the finger pressure and two specialty left-hand finger action-events (figure 4.2.7) linked to pressure:

| pressure | action-events |

|---|---|

◦  |

◦  |

◦  |

◦  |

◦  |

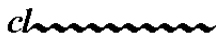

From other left-hand finger-specific actions (figure 4.2.7), Cassidy also makes use of:

- ◦ : triller, with adjacent finger

- ◦ : triller with non-adjacent finger

- ◦ : left-hand pizzicato

- ◦ : left-hand pizzicato behind (under) the stopped finger.

Figure 4.2.7: Left-hand finger-actions

Because the left hand is quintessentially linked to pitch in violin playing, I initially found the left-hand parameter disorienting. It demanded the expansion of tools for how the hand is used and guided, where “precision” is not really related to a specific pitch location and guided by the inner ear to reach it, and also where constant “gliding” is not just random glissandos and hand moving up and down the fingerboard. In a more standard piece, one of the elements that determine the precision of movement of the left hand is aiming for accuracy of the pitch, which is achieved through exact mapping of the fingerboard – learning this very precise relationship between the trajectory of the left hand and the place where the finger must block the string in order to achieve the exact pitch. Whether I am learning fast-paced scale-like motives (figure 4.2.8) or jumping to a distant interval note (figure 4.2.9), all horizontal and vertical gestures of the left hand are part of one collective movement that has as its absolute goal a trajectory from clear point A to a clear point B in relation to the pitch mapping of the fingerboard.

Figure 4.2.8: Niccolo Paganini’s Caprice Op.1 no.5 (excerpt from the introduction)

Figure 4.2.9: Niccolo Paganini’s Caprice Op.1 no.9 (bars 60 to 64)

For The Crutch of Memory, I found that I had to think of the left hand in a somewhat different way. The “gliding” movement of the whole arm and the hand up and down the fingerboard, a movement closely resembling a glissando, is not just a means to reach a distant place on the fingerboard. I reached this notion because of the subset of movements, the widening and tightening of hand’s scope, that are independent from the general position of the arm in relation to the fingerboard. What I found is that, for my understanding of the piece, this subset of movements created a notion that the sound is not in the instrument, but in the hand. Rather than the hand having a task of searching for the melody that is in the instrument and “located” on the fingerboard (and will be released by reaching a specific pitch), the sound of what is played is trapped inside of the hand. As the hand is moving, widening and tightening, these physical actions control and release the physical melody into sound. For the fingers, as seen in figure 4.2.1, the fingerings have a fixed string they have to be on, but there is no exact determined pitch. The length of the fingerboard is mapped by the seven positions for the hand, but the widening and tightening of the fingers and continuous motion of the hand create a larger margin of indeterminacy regarding “precision”. Or, it demanded rethinking of how to achieve this specific kind of precision. In my work on the piece, I found that I must think of the stopped finger not directly and solely related to the location of the pitch-mapping of the instrument but its relative position within the frame of the moving hand. Meaning that the finger and palm are not leading the hand and arm, as in more standard, portamento-like position shifting when the goal is exact pitch but is just following the global hand position while being perceptible to the adjustments of specific widths.

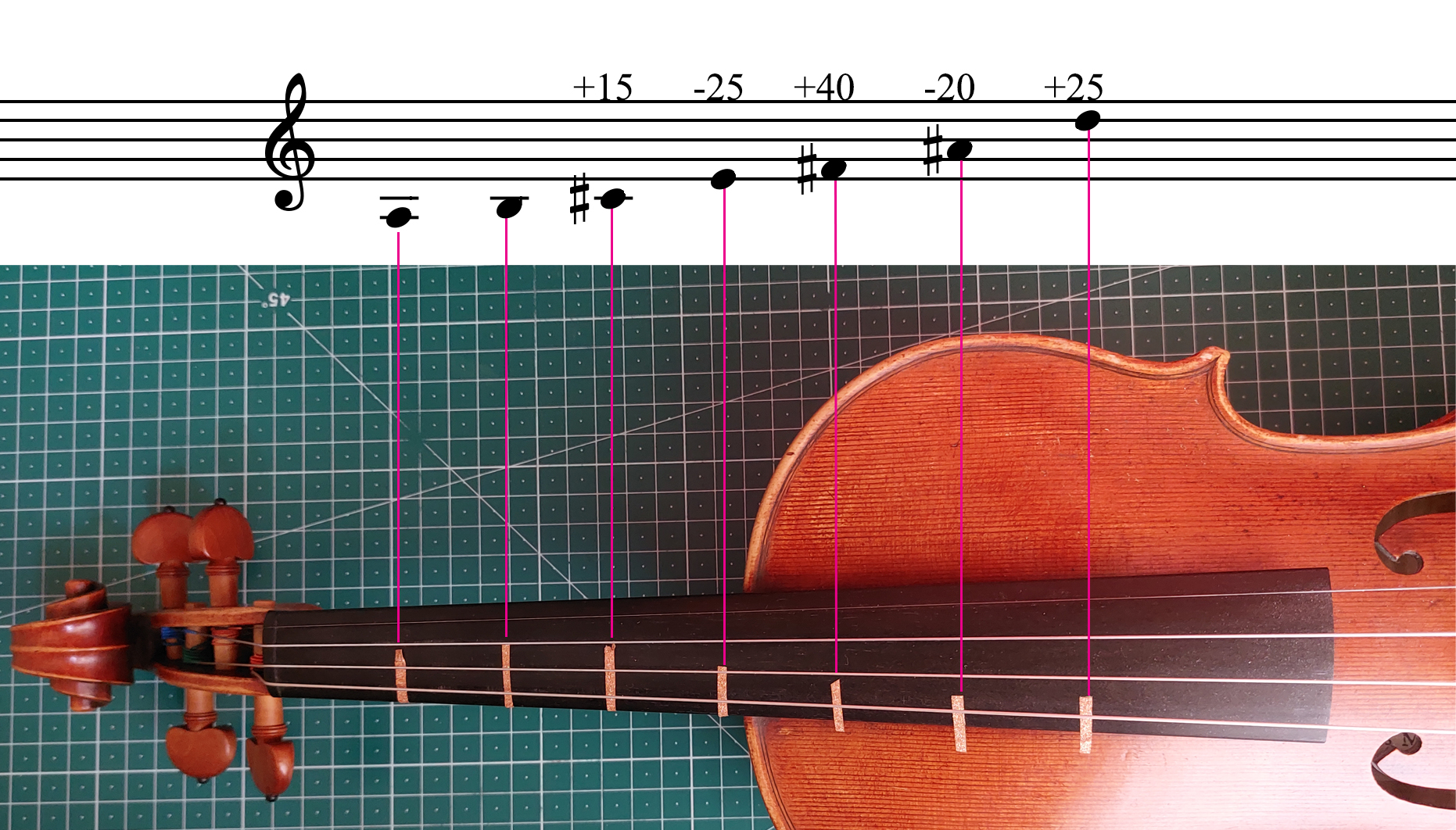

The beginning phase of work was dedicated to training the hand for the seven-position fingerboard mapping. At first, getting to know the work, I worked on the piece using the standard diatonic seven position division, which also does not sound as standard when scordatura is taken in consideration. The immediate next phase of work was to devise and practise seven equidistant positions.[5] To do this, I would practise moving up and down on the fingerboard on one string at a time, starting from keeping the physical spacing between the first and the second finger at a distance of one whole tone (which would be equivalent to distance of the first and the second position). In standard notation and starting from the standard first position with first finger placed on A3 (220 Hz) note on the IV string, the mapping of the fingerboard would look approximately as seen in figure 4.2.10. The distance between each position is approximately 3 cm.[6]

Figure 4.2.10: Example of mapping of the fingerboard in seven equidistant positions, on IV string, starting from first note being fingered at pitch equivalent to A3 (220 Hz) in standard tuning

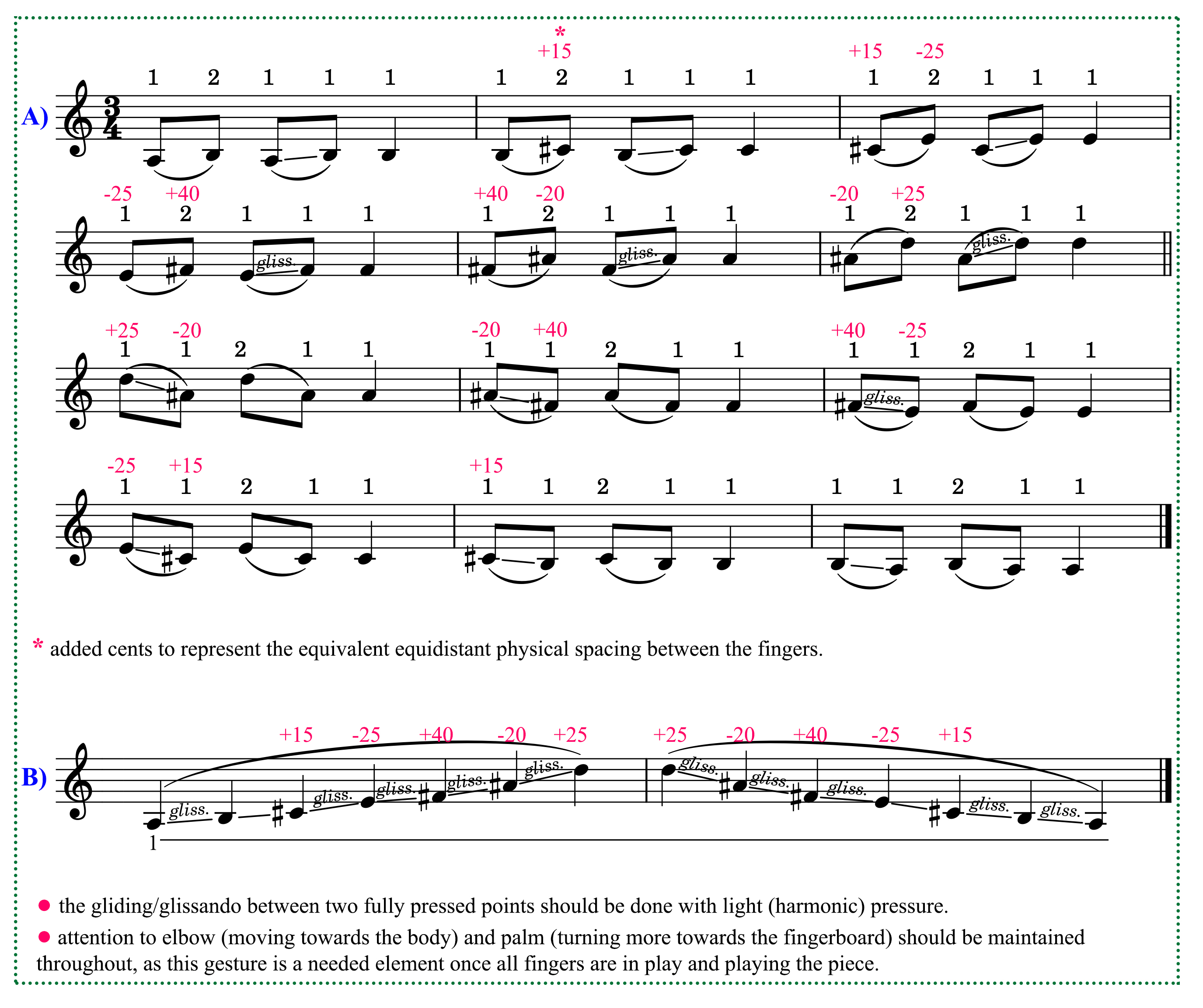

An example of the exercises for getting the hand accustomed to feel and embody this kind of division of the fingerboard can be translated to standard notation as follows (figure 4.2.11):

Figure 4.2.11: Example of exercises for training equidistant seven-position mapping of the fingerboard, example on IV string, starting from first note being fingered at pitch equivalent to A3 (220 Hz) in standard tuning

I would repeat these exercises on all strings. The focus and attention were always on the feeling in the hand, arm, and the elbow. The exercises would then be repeated starting from selecting one pitch between what is in standard tuning G eight-tone-sharp and A three-quarter-sharp (and notes on parallel positions to these on the other strings) as the beginning note. I would choose different physical interval distance between fingers, creating a different mapping outcomes. Although the performance notes do not explicitly say that the first position must remain in the lowest register, I always approached devising the positions from this point as it allows for a greater overall range in the piece. Disassociating positions from the standard diatonic mapping of the fingerboard opened a wider range of freedom and independence for the hand, thus allowing for inventing my own seven-position mapping to occur in a later phase of work. The exercises facilitated a possibility to have different variations that are maintained in the hand as “work in progress” and then, once a performance date approaches, I would decide on one specific seven-position approach to work with focus. Illustration of different approaches can be seen in figure 4.2.12.

Figure 4.2.12: Illustration of different approaches to left-hand position and tuning in Aaron Cassidy's The Crutch of Memory

Although the piece does not employ fast scale-like passages in the style of those seen in figure 4.2.8, there is a need for fast, agile reaction of fingers and dexterity of actions. To extend all the mechanical parameters of the fingers, I devised separate finger exercises (figure 4.2.13) which I found helpful in developing comfort and confidence in each of the five hand-frames. Their goal was to extend the embodied feeling of finger distances between fingers from the diatonic and microtonal interval pitch-related spacing and strengthen the feeling that simply relies on the physical distances felt in the hand. Besides the four fingers that are in movement, during practising of these exercises a special attention is to be given to the thumb movement and hand’s natural turning towards the fingerboard as the finger spacing becomes wider. This is an element that, in combination to elbow, create a more relaxed state for the hand and allow for wider stretching without creating too much stress or injury, which is particularly important in the fifth finger spacing.

Figure 4.2.13: Exercises for the mechanical parameters of finger spacing

In the first round of practising, I would play the exercise with a bow, where greater concentration is placed in feeling the gesture inside the body and using the sound only as supplementary control. Then the exercise would be repeated without the bow and in as many repetitions as needed until the feeling settles in. After the sensation of the first width would start to feel comfortable, I would repeat the same exercise for the second degree of width, and so on until I would go through all five degrees of finger spacing. Once finishing the cycle, I would move to the next position and then next string, as each position and string need a slightly different angle of the hand. After practising for a while in order starting from first to fifth width, I would make small patterns, still within one position but with random changes of width. After the hand has gotten accustomed to all five hand-widths, I would practise hand-width changes in their respective rhythm taking one phrase at a time from the piece (figure 4.2.14), and building until rounding up the whole piece.

Figure 4.2.14: Example of a phrase from Aaron Cassidy’s The Crutch of Memory, bars 11 to 16 (The image has blurred material, to emphasise what was the focus for practising)

Just like with exercises for finger spacing changes, I would apply the same approach of working only on the material from the first and the third stave one at a time, with its rhythm and as appearing in the piece. After practising exercises that allowed for fine tuning of my left hand’s sensitivity and sensibility in relation to the fingerboard mapping, hand position, and finger spacings, I would work on first two (finger spacing/width and hand position) and then all three (fingering, finger spacing/width, and hand position) aspects of the left-hand movements together. This was the stage in which I would only work with the material from the piece, taking smaller segments and phrases, and practising without the bow. The added element of difficulty is that each of the left-hand actions has its own rhythm, hence creating a nested polyrhythmic gesture within a movement. In my approach I interpreted this through thinking of rhythm as local and global speed, where local speed is the speed of changing the finger spacing from the second stave and vertical finger-actions coming from the top stave, and the global speed is the gesture of hand changing positions.

The dynamics in the piece are notated and intended in a conventional way, as Cassidy emphasises in the score and in the work sessions, but the structure of the piece inspired me to look for another way of thinking about the application of dynamics and volume. When all the parameters come together, within each hand individually and between the left and the right hand, they can have seemingly opposing and even impossible meanings and outcomes. In my reading of the piece, and as means of facilitating bridging the difficulties of so many individual parameters in play, I explored understanding the dynamics not only as volume of the loudness of the sound, but also the volume of the imagined sound vibration that is contained in the hand and manifests itself as the intensity of the gesture. Thinking of the volume also as the indication of the intensity of action, for me had a soothing mental effect that reinforced all the gestural sensations embodied through practising and, without putting to the second plane the aim to interpret the dynamics in their traditional meaning, allowing the volume of sounding, the loudness and softness, to become natural byproduct of the treatment of gesture, and the interaction between the technology of the body and the instrument.

In addition to all the mentioned technique and gesture related aspects of the piece that I must take into consideration when playing, there is another technical parameter related to the instrument and the timbre – the tuning. I have approached the suggestions for tuning in some performances literally following the suggested tuning, but bearing in mind Cassidy’s indication that ‘other tunings are possible’ if specific guidelines are followed, I have also explored alternative ways to broaden the range and timbre of my instrument.[7] To do this I have used D’Addario’s octave (low) violin strings and explored stringing the instrument only with one set of strings at a time or mixing normal and octave-low strings.[8] Using different types of strings created different string tensions and resulted in different responses of the string when playing. Embodying the material through physical sensations of gestures within the body and linking them with their sonic outcome, as well as thinking of volume of intensity of gesture, all created greater control, sensitivity, and ability to react and adjust to situations and circumstances that are related to the technology of the instrument prompted by the scordatura.

- [1]Aaron Cassidy, The Crutch of Memory, for indeterminate string instrument (any bowed, non-fretted instrument with at least four adjacent strings), Self-published, SKU:200402 (2004), p.I.

- [2]Aaron Cassidy, The Crutch of Memory, p.I.

- [3]Besides the ordinary point of contact (area in and around the middle between the bridge and the fingerboard), Cassidy in this piece uses six more positions: molto sul tasto (abbreviation mst; widely exaggerated and well onto the fingerboard), sul tasto (abbreviation st; over the fingerboard), poco sul tasto (abbreviation pst; a very slight timbral modification in direction over the fingerboard), molto sul ponticello (abbreviation msp; on the bridge and nearly toneless bowing), sul ponticello (abbreviation sp; very close to the bridge but not on the bridge), and poco sul ponticello (abbreviation psp; a very slight timbral modification in the direction of the bridge). There are five bow pressures: (1) molto flautando (light, delicate, wispy); (2) poco flautando; (3) normal bow pressure; (4) poco pesante; and (5) molto pesante (a heightened degree of bow noise, particularly at the initial attack; nearing scratch tone).

- [4]Aaron Cassidy, The Crutch of Memory, p.II

- [5]This was a personal choice, as it seemed a more interesting, challenging, and musically enriching approach.

- [6]Considering lengths in cm when mapping the fingerboard comes from the experience and playing the piece “violin” by Robert Wannamaker, where, for the purpose of his piece, in the third movement he referred to the left-hand position along the length of the strings in cm measurements. Although not absolutely necessary to think in cm division of the fingerboard, having in mind also this way of mapping and retaining the distances inside the hand through thinking in cm, in my case has proven to be a useful additional tool. The piece is part of my performance repertoire and my research supplementary repertoire list.

- [7]Cassidy, p.I

- [8]Combining different types of strings, and then applying retuning, included: octave low G in place of standard G string, octave low A in place of standard D, standard A and E; octave low D in place of standard G, standard G in place of standard D, standard A and E; octave low G in place of standard G, octave low A in place of standard D, octave low E in place of A, and standard E.