4.1 Physicality Interpreted as Material in Dmitri Kourliandski’s prePositions

In program note for prePositions, Kourliandski writes that:

- The piece represents an extremely complex, saturated texture. It is impossible to achieve the exact interpretation of the musical text – it turns to be an ideal object which an interpreter has to follow but can never reach… The distance between the musical text and the performer, between the text and its actual interpretation, is the main material of the composition.[1]

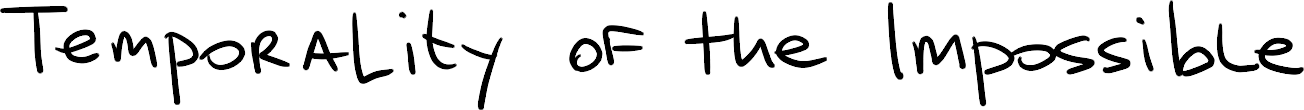

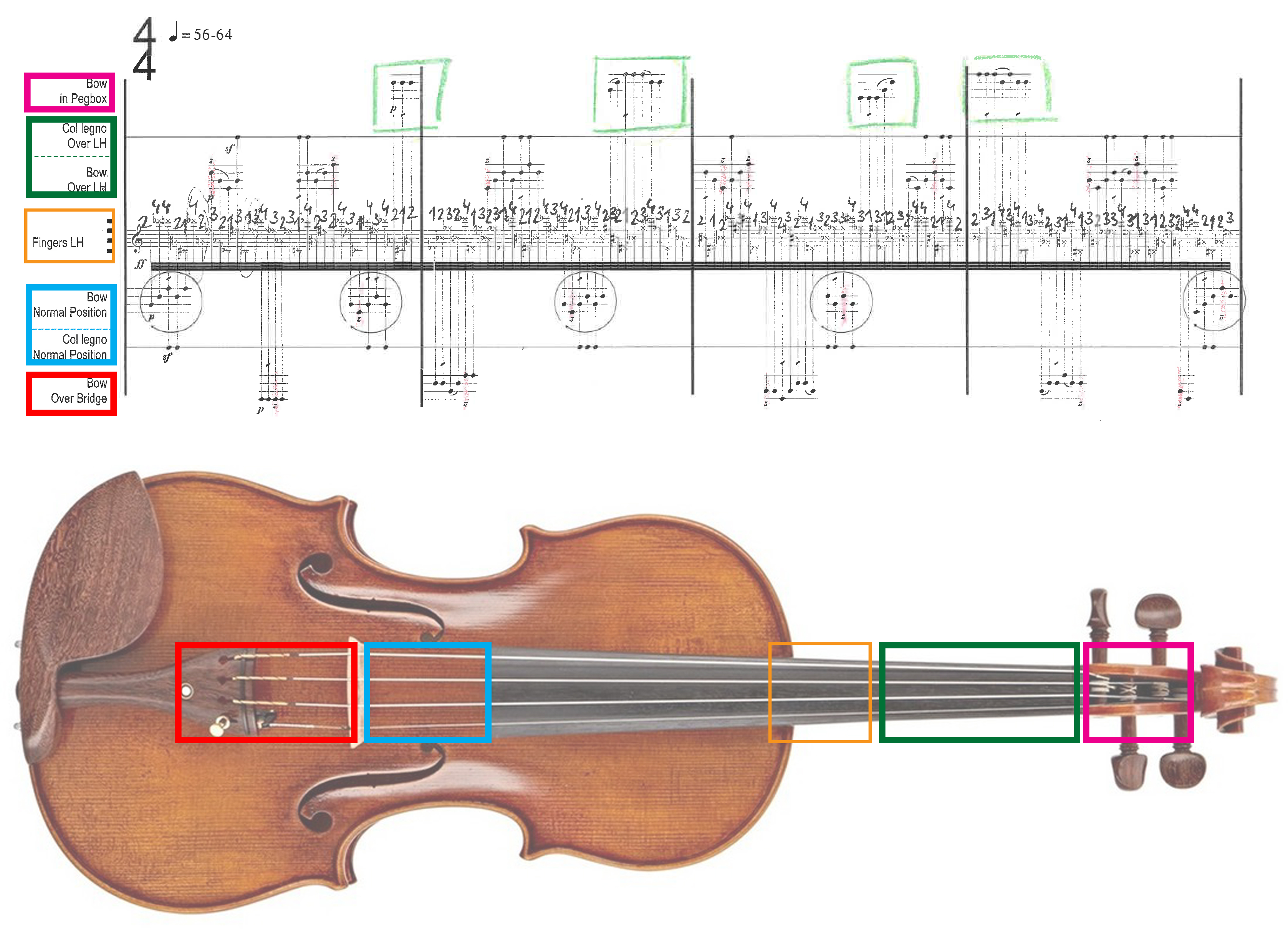

The piece is notated in a seven-staff system. The fourth system is dedicated to the left hand, and the upper three and lower three systems to the actions of the right hand with each line being mapped to the portion of the instrument (figure 4.1.1). With the exception of 12 bars on page five and page seven each, and a section of 32 bars on page six where left- and right-hand actions come together in a more traditional way of writing (annotated as ‘normal playing, legatissimo’ as can be seen in bar six in figure 4.1.2), the remaining 108 bars of the piece maintain independent and separate treatment of actions for the left and the right hand.[2] Kourliandski writes in the performance notes that the ‘performer has to achieve the maximum possible differentiation of sound between each line and each playing technique, as if each line is played by a different, separate musician. The piece is to be treated rather as an ensemble piece than as a solo one.’[3] Observing the behaviour of my body during my first tryouts of the piece, I noticed the extreme gestural virtuosity that is imposed with the way the right-hand playing techniques in combination with the mapping of the instrument were used. The instruction ‘as if each line is played by a different, separate musician’ and with the notion that the musical text cannot be achieved through the more conventional assumptions regarding how music text is translated into sound, amplified the shift in my focus to be on gestures, the separation of gestures of the hands from each other, and from expectation of one fixed acoustic outcome.[4]

Figure 4.1.1: Dmitri Kourliandski’s prePositions (2008); diagram of points of contact with an excerpt from page one

Figure 4.1.2: Dmitri Kourliandski’s prePositions for solo violin, excerpt from page five

While working on the piece, I defined two different approaches to motives. One being the quick and frantic material of the left hand and short, sharp cut, and equally frantic small units of gesture for the right hand, like the material that can be seen in the four bars in figure 4.1.1. The other is glissando in the left hand and the right hand linked to sounding out the glissando in a more common manner, the “normal playing, legatissimo”, as in bars 6 to 8 of figure 4.1.2.

For the left hand Kourliandski writes,

- all episodes with 32nds are rather represent an ‘image of the desirable texture’ than a concrete text to be performed precisely […] the written sequence of pitches in these episodes […] can be performed approximately. It is an “ideal text” which can’t be realised precisely but can be only imitated.[5]

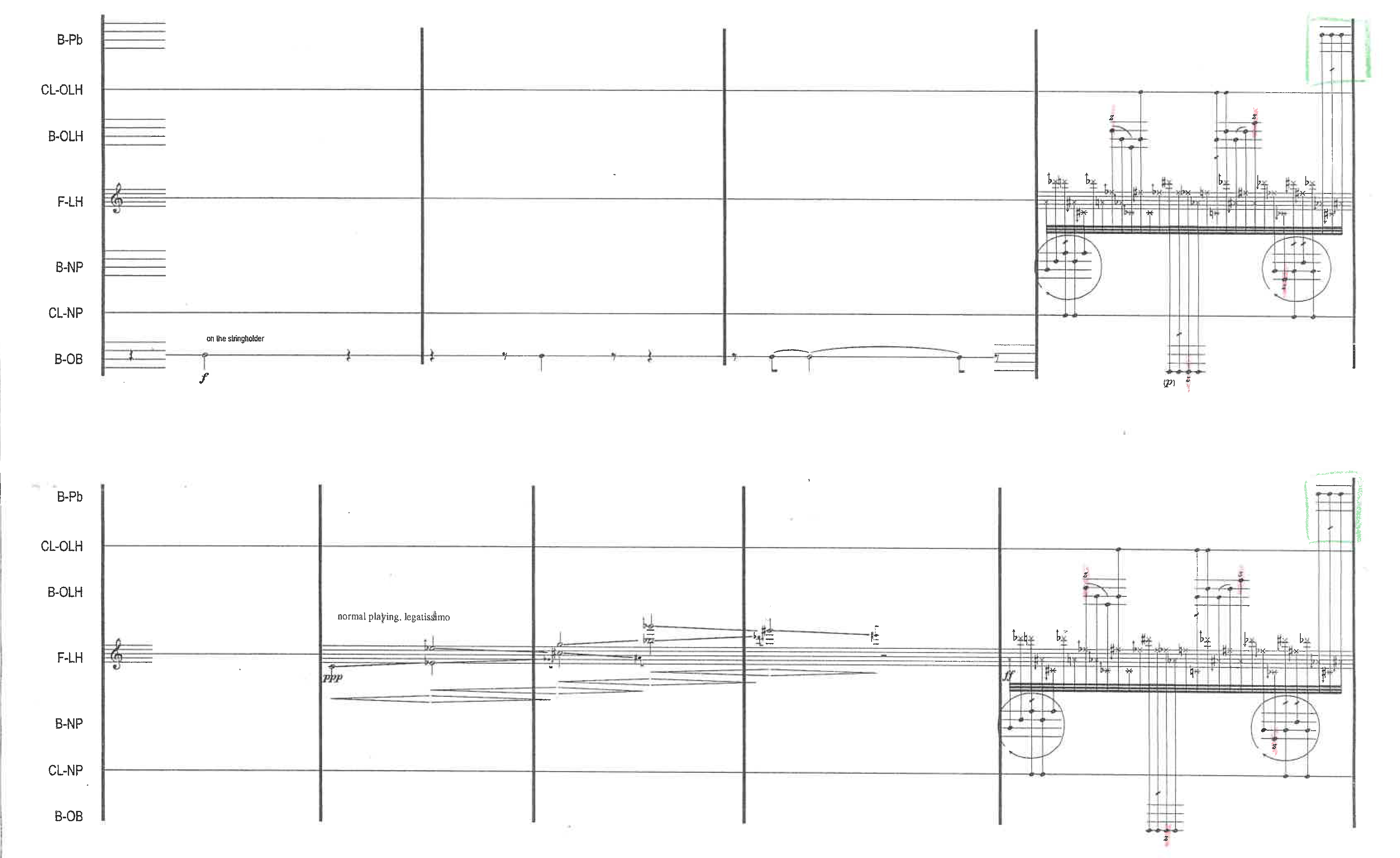

All the pitches in these sequences are happening around c3–a4–f5–d6, on IV (G)–III (D)–II (A)–I (E) strings respectively. The left hand thus is placed and remains throughout these sequences in the standard third position (area of the fingerboard marked in orange in figure 4.1.1). To achieve the desired dense texture with strong tapping of the fingers I practised these sequences devising a finger pattern mechanism training, partially inspired by the exercise number I.A. for left hand without bow from Carl Flesch’s Urstudien für Violine.[6] Considering that there are no returning pitch-patterns in the sequence that can facilitate creating chunks of patterns to be memorised, my approach was to start by working one bar at a time and then connecting bars, thus expanding until the entire sequence. The exercises were done without bow, with strong finger tap followed by immediate pressure release, but without lifting the finger off the string. I would start the exercise in slow tempo and work towards fastest possible, working through five rhythm patterns (figure 4.1.3).

Figure 4.1.3: Five starting patterns for the left-hand fingers

The eighth, dotted eighth, and the sixteenth values are here as demonstration of “long” and “short” note proportions. While the starting point with the dotted rhythm exercises is to play the exact proportion of the rhythm, as speed is built the long note in the exercise becomes longer and the short note shorter, in both first and the second exercise pattern. Furthermore, the short note becomes as short as possible, cut from the previous note, and as linked as possible to the following note. Alternating practising with dotted rhythms is a great ally in developing speed in the finger action. The focus in these exercises is always on the sensation in the hand and fingers. While the attention should be predominantly on physical sensation, there should also be some care to listen to the tapping sound and pitch it produces. As the texture takes priority over pitch, listening to the pitch along the tapping is only a means of control to aid, assess, and train the firmness and pressure of the finger – a too gentle fall of the finger will produce a hollower tapping sound. Combined attention to the physical sensation in the hand and aural listening in the early phases of practising, strengthens the understanding of dynamic, control, and release of the gesture that helps avoid harmful tension while maintaining the necessary strength. As exercises reach faster tempo and fingers become faster in executing the sequences, the attention remains on the sensation in the hand, fingers, and fingertips.

Figure 4.1.4: Excerpt from Dmitri Kourliandski’s prePositions

As it can be observed in the video in figure 4.1.4, achieving the desired texture means that, although the left hand remains relatively static in its position, the extreme dexterity and tapping of the fingers adds to the overall gestural virtuosity of these sequences. It is however the actions of the right hand that particularly highlight the gestural aspect of the work. The travelling position of the point of contact (see figure 4.1.1) demands from the right hand a fast, at times frantic, succession of changes. These actions are happening completely independent and detached from anything that is happening in the left hand. All sonic outcomes that are produced are not linked to a specific pitch but arise as by-product of an immediate moment of bow touching the string and the specific textures of the sound are determined by the gesture itself (such as circular bowing, flip of the bow to col legno, pressure changes). The right-hand movement essentially amounts to the gliding of the arm along the length of the instrument, and in my interpretation, which I discussed with Kourliandski, it becomes a right-hand glissando (figure 4.1.5), and through this understanding connects to the second material area: that of the left-hand glissando.

Figure 4.1.5: Perceiving right-hand motion as glissando

To arrive at as dense and as precise an execution as possible of all right-hand actions in a sequence, I approached the work by working one bar at a time and exclusively on the right hand. I would first decipher the gestural details each action occurrence demands. Each action occurrence would then be practised with four-time repetition. After the fourth repetition, the exercise continued by immediately passing to the next occurrence, which was then also repeated four times. I would continue like this until the end of the bar. The reason for the immediate repeating of the same action is to strengthen each action on its own, and not making pauses between the occurrences helps to keep the tension on the end of each occurrence (gesture), by having the direction towards the next action, thus creating a more accurate situation to the performance. After multiple repetition of a bar with four-repeat process, I would do the same but with only three repetitions of the action occurrence, then only two, until arriving at the execution as written. After each bar has been completed, this pattern of exercises is then applied in connecting two, and then three, and so on bars, until a full sequence. During the process of practising the right-hand actions, I would mute the strings, as the absence of sound allowed me greater focus on gesture and feeling in the body, further securing its embodiment from the physical sensation.

Once both hands had gone through their practising regimes for building their own separate and individual material, I started working on setting them in motion at the same time, as written in the score. I would then apply the same repetition model of practising from one bar to full sequence. The multiple repetitions also helped build up the physical stamina, focus, and concretion necessary for the performance. The longest uninterrupted sequence of this kind of extreme actions (left and right hand independently) in the piece is eight bars long.[7]

The left-hand glissando sequences start to appear on page five of the piece (figure 4.1.2), with four 3-bar sections interspersed with one bar of the frantic material between each appearance. On page six, the glissando material becomes dominant, with eight 4-bar sections (with silent bar before each), after which it retreats during page seven through the same formation as when introduced. These sequences are a type of material that could be said to fall in the common left-right hand coarticulated gesture with a specific sound goal as the starting and ending point. While at first moment these passages might appear to have the expected sonic character for glissando, Kourliandski achieves an exciting poly-sonic outcome by use of individual, opposing direction for each of the notes in double-stop (only the first and the last note of each section is a single note). In this bi-directional glissando, with the separation of fingers from each other, there is a separation of gesture within the global movement of the hand. In addition, each note in the double stop has its own dynamic – one crescendo and the other decrescendo – requiring the right hand to create two different gestures within one movement. This bi-directionality and poly-sonic glissando outcome amplify the feeling of having different musicians playing at the same time. Practising these sequences entailed:

- ◦ dividing each section in its five (3-bar sequence) or eight (4-bar sequence) notes and firstly practising each glissando separately

- ◦ adjustment of angle and pressure of the right hand to achieve double dynamic (crescendo and decrescendo) with a single bow stroke

- ◦ connecting ending of one double stop with beginning of the next with appropriate dynamic shading

- ◦ connecting each of these elements into a full sequence.

Even though there is a “normal” and “traditional” aspect to both writing and the sounding of the material in glissando sequences, the separation of fingers and dynamics within one movement conveyed gestural energy, density, and virtuosity, bringing two seemingly very different materials, this glissando with coarticulated actions of the left and the right hand and the sequences with separated left and right hand, as one whole. Working on the piece using the approach of focusing on embodying movements and gestures through their physical characteristics detached from their final sounding helped in navigating through the material with more confidence and conviction.

- [1]Dmitri Kourliandski, prePositions, Program Note (2008) https://www.henry-lemoine.com/en/catalogue/fiche/JJ2072 [accessed 25 May 2023].

- [2]Dmitri Kourliandski, prePositions, Editions Jobert No. JJ2072 (Paris: Editions Jobert, 2008), p.6.

- [3]Dmitri Kourliandski, prePositions, in Performance Notes.

- [4]Kourliandski, in Performance Notes.

- [5]Dmitri Kourliandski, in Performance Notes.

- [6]Carl Flesch, Urstudien für Violine, Edition Ries & Erler (Berlin: Ries & Erler, 1955), p.11.

- [7]Last two bars of the third page and following six on page number four.