3.2 Establishing Potentials of Sonic Identity in Pieces with Alternative Tunings

Finding a sonic identity in case of alternative tuning is a specific task for each scordatura and piece. Each alteration of the tuning, in combination with all the other musical materials in the piece and their interactions, influences the sonic outcome. Before embarking on tackling the details from the piece and creating an interpretation, I found that it is important to discover and create an initial feeling of the timbral world a specific scordatura opens up and of the potentials of this sonic environment (figure 3.2.1). The process is based on careful listening through the heard (listening with the ears) and the felt (listening with the body).

Figure 3.2.1: Listening: potentials and sonic environment of three scordaturas (in examples of Johnson and Cassidy)

In my practice, this is a two-stage process. In the first stage, exercises are done working only with open strings, followed by the second stage in which different levels of left-hand finger pressure are tested. Knowledge about the potentials of the sound, its production and its sound, to great extent, comes from the sensitivity and sensibility of the left hand, and of the fingers of the left hand in particular. I have named this the vertical gesture. Focusing on this relationship between the finger and the string allows for another type of location to emerge.[1] The changeable depth of space that exists between the finger and the string reveals much about the potentials of the sonic identity from the outset; in Einarsson’s words, a ‘point opens up, receives degrees, becomes bi-directional, and becomes equally important as the fingerboard space’.[2]

The two-stage work process is as follows:

- ■ Listening to bowed open strings

- ◦ Playing one string at a time

- ◦ Playing two strings: IV+III, III+II, II+I

- ◦ Considering that all the pieces from my focus repertoire make use of both sul tasto and sul ponticello contact points, the open string process of playing individual strings and then two strings simultaneously should be repeated playing: sul ponticello, molto sul ponticello, sul tasto, and molto sul tasto.

- ◦ It is useful, for each of the steps, to go through a range of dynamics from pp to ff. More specific explorations of both extremely soft and extremely loud in combination with bow pressures are part of working with the exact material form the piece, but if time allows it is also advisable to explore different effects of different bow pressures.

- ■ Exploring potential effects in combination with different left-hand finger pressure[3]

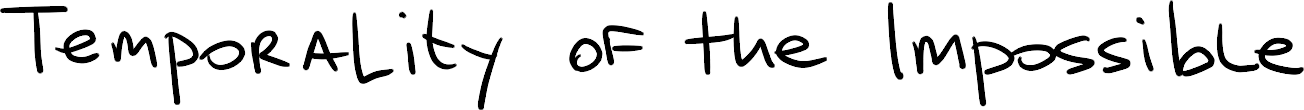

- ◦ Exercise 1: Playing long bowed notes, alternating between open string and natural harmonic. Exercise is repeated with only one harmonic at a time. Lifting of the finger to the open string should be done very slowly, so that the point of release of the string can be felt in the finger. Choice of finger is free, and it is desired to be alternated, so that each finger participates in the sensory exploration (figure 3.2.2)

Figure 3.2.2: Exercise 1 - ◦ Exercise 2: Playing a long bowed note, fingered on:

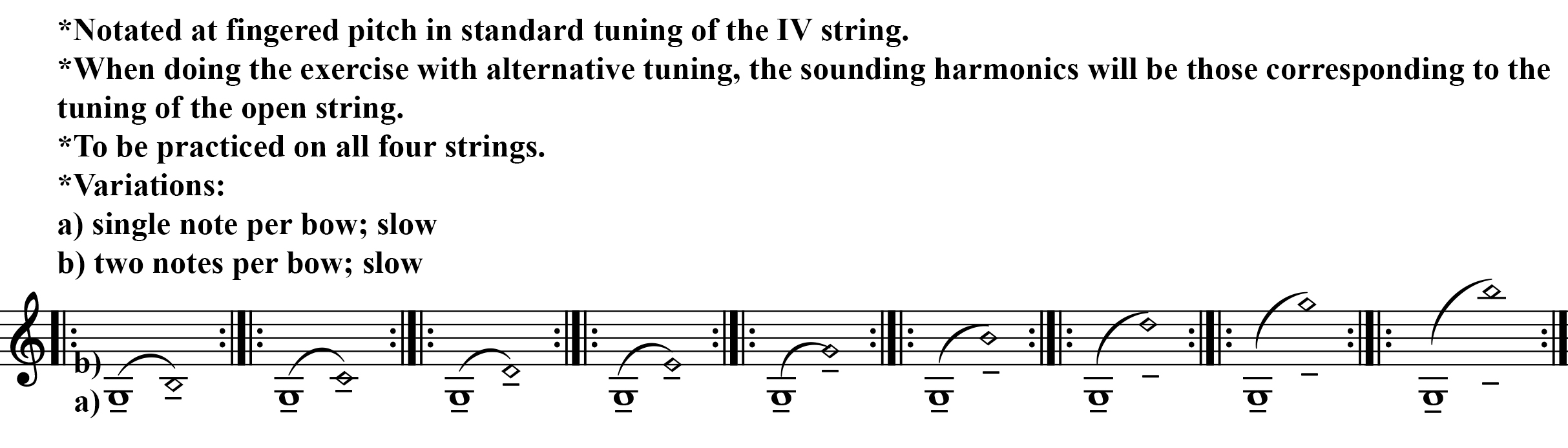

- • Exercise 2A: the interval of an octave, starting with fully depressed finger, and then altering the finger pressure during the playing all the way to minimal lifting off the string (with briefest sounding of the open string), and going back. Choice of finger is free, and it is desired to be alternated, so that each finger participates in the sensory exploration (figure 3.2.3)

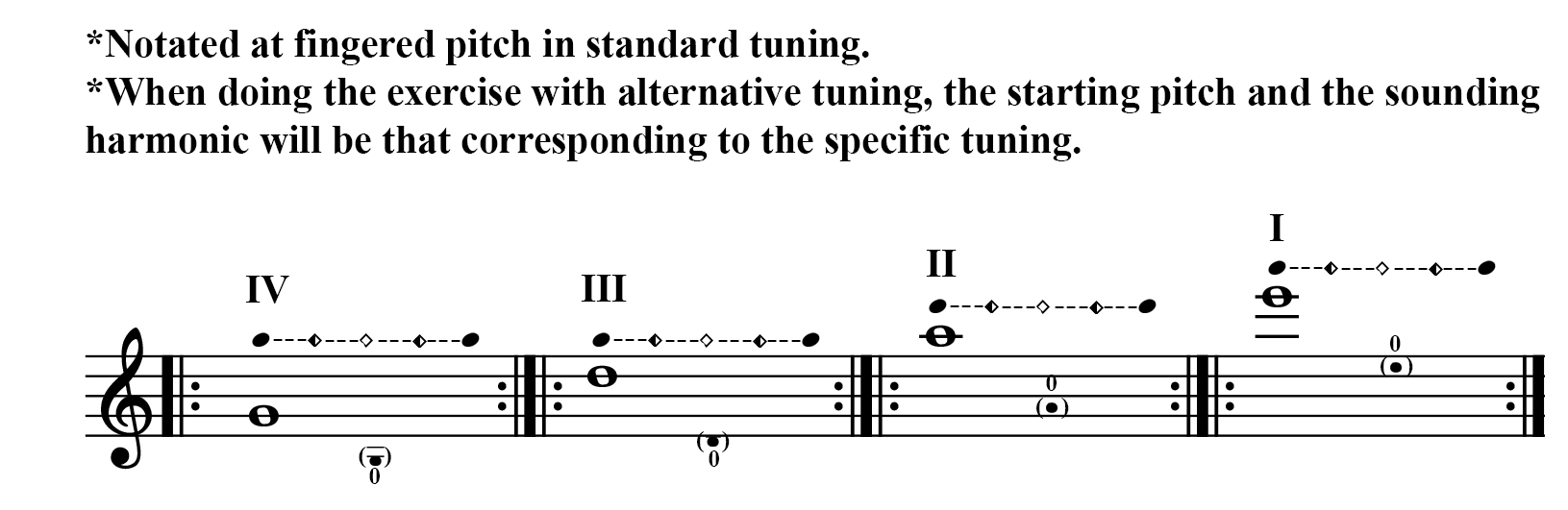

Figure 3.2.3: Exercise 2A - • Exercise 2B: the interval of a fifth, starting with a fully depressed finger, and then altering the finger pressure during the playing. Choice of finger is free, and it is desired to be alternated, so that each finger participates in the sensory exploration (figure 3.2.4)

Figure 3.2.4: Exercise 2B

- In later phases on working on the piece, depending on the demands and necessities of the piece, these exercises can be applied to explore any finger-stopping-location on the fingerboard

- • Exercise 2A: the interval of an octave, starting with fully depressed finger, and then altering the finger pressure during the playing all the way to minimal lifting off the string (with briefest sounding of the open string), and going back. Choice of finger is free, and it is desired to be alternated, so that each finger participates in the sensory exploration (figure 3.2.3)

- ◦ Playing a long-bowed unison double stop between: IV+III, III+II, and II+I string, where:

- • The lower string has a fully depressed finger, fingered on the pitch of the higher open string

- • The lower string is played as open string and the stopped finger is fingering an octave, or multiple octave-distance, on the higher string

- During the exercise, there should be attention to sympathetic resonance and vibration of the open string. The exercises also have a practical benefit in getting a better grasp of possibly altered relationship of levels and tensions of the strings, and possible alterations to angles the bow will have to account for when playing.

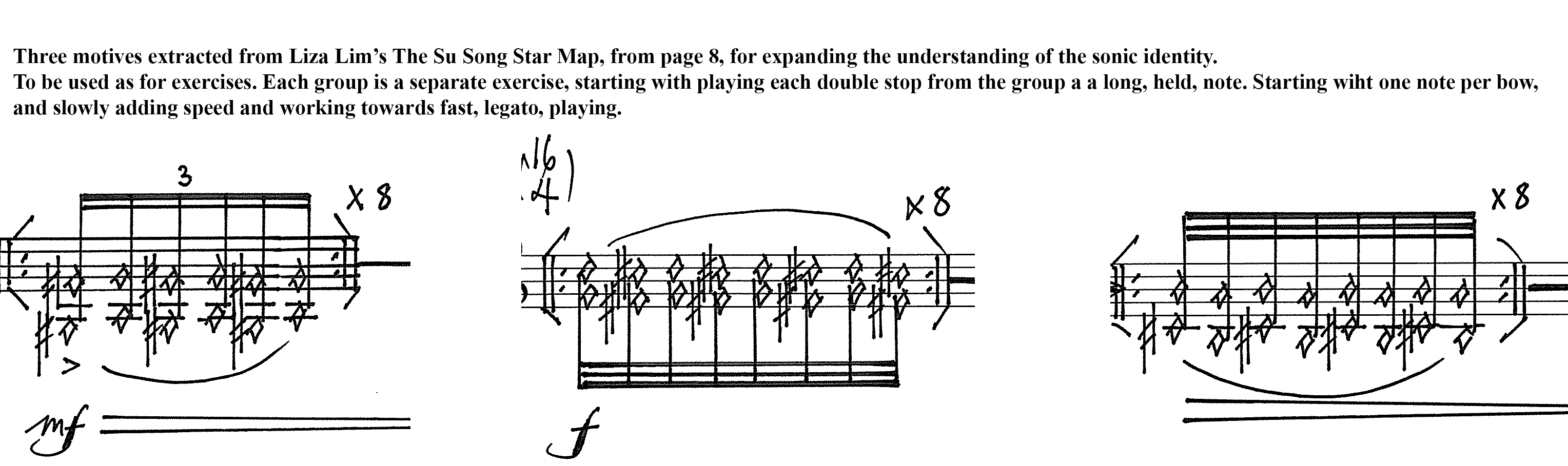

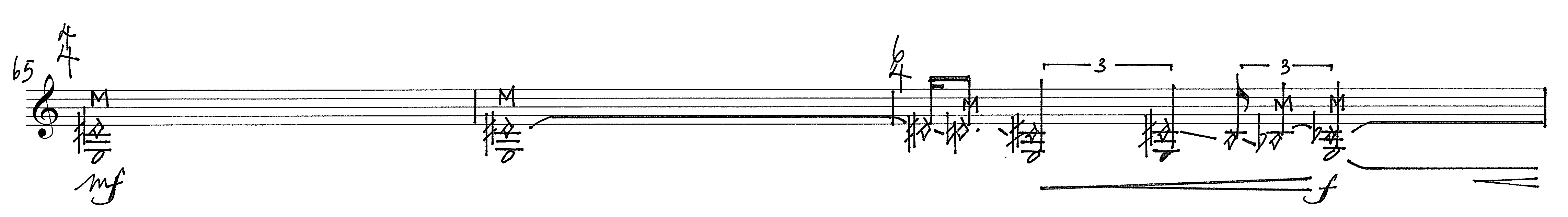

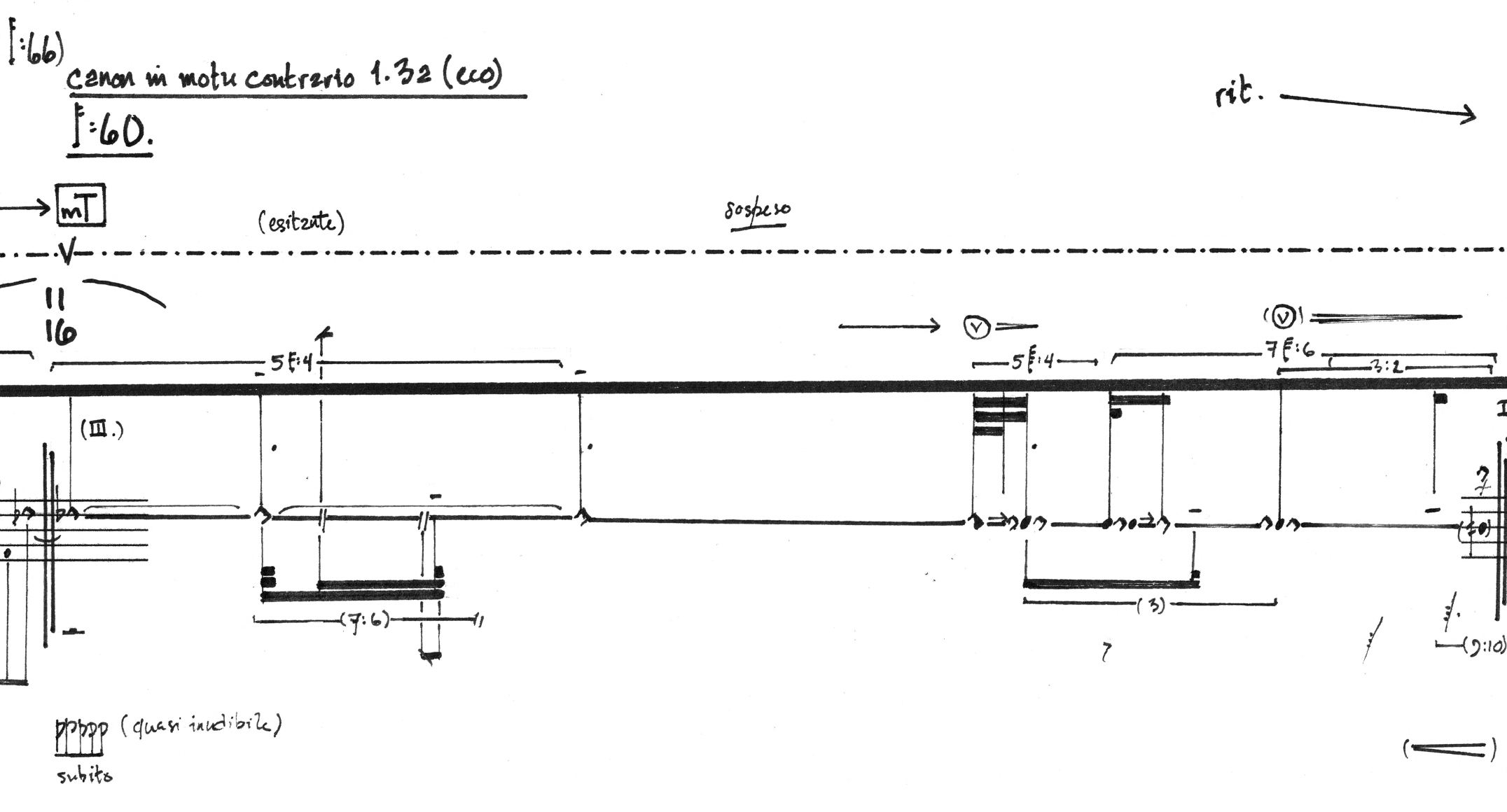

- ◦ When possible, working with a selected motive or sets of motives from the piece (figure 3.2.5, 3.2.6, and 3.2.7)

Figure 3.2.5: Motives from page 8 of The Su Song Star Map to be used as exercise

Figure 3.2.6: Motive from page 11 of The Su Song Star Map to be used as exercise

Figure 3.2.7: Motive from page 3 of Wolke über Bäumen to be used as exercise

There are four important points that must be kept in mind throughout all exercises of both stages of work. They are as follows:

- ■ Take time. In more drastic alterations of tuning, take even more time for both single string and double stops, and even more for testing finger pressures. Do not rush the process.

- ■ Maintain attentive and careful listening with the ears.

- ■ Maintain attentive and careful listening with own body:

- ◦ Listen through the left hand’s fingertips. Let the sound vibration enter the body, and mind, through the skin of the fingertips

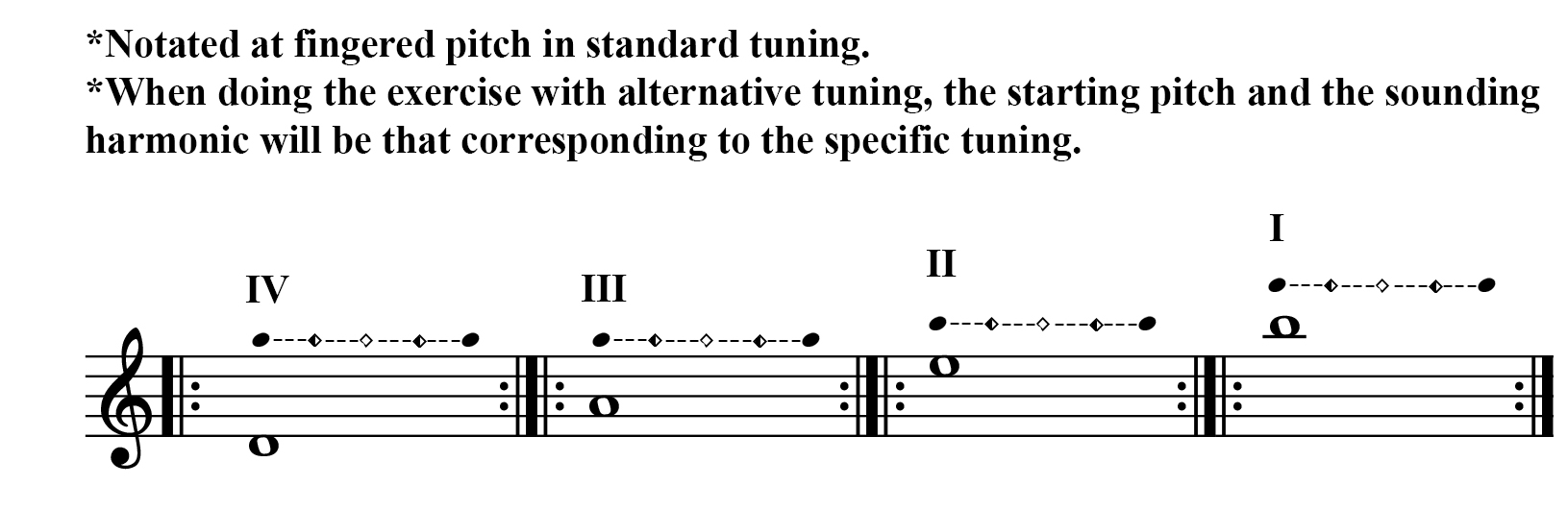

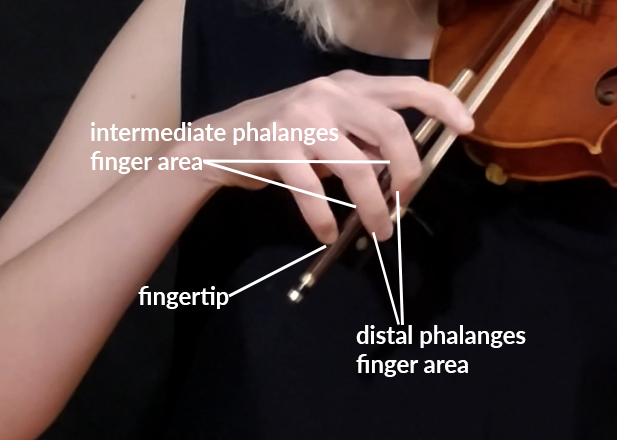

- ◦ Listen through the tips of the right-hand thumb and little finger, and the distal and intermediate phalange areas of the index, middle, and ring fingers (figure 3.2.8)

- ◦ Listen with the neck: through the point where the body of the instrument is in contact with one’s own body

Figure 3.2.8: Areas of finger’s contact points with the bow, in the bow-hold adjusted for playing on the tailpiece.[4]

- ■ Listening to the physical responses of the instrument’s body

- ◦ Scordatura changes the tension of the string and the balance of tensions between the strings. For this reason, there is a higher probability of changed reaction and responsivity of setting the string in motion. Time should be spent listening and assessing the strings response and responses between the strings with both bowing and pizzicato interaction.

- [1]This is further elaborated in chapter 4.2 [Please see full Thesis, available via University of Huddersfield's repository.]

- [2]Einar Torfi Einarssohn, Negative Dynamics I(a/b): Exegesis (2011) http://einartorfieinarsson.com/text2.html [accessed 24 May 2023].

- [3]It is important to note that individual violins, types of strings, string tensions, bridge heights all play a role in issues addressing vertical distance, and all these parameters must be taken in consideration accordingly when working on a specific instrument.

- [4]Points of contact can vary depending of individual ways of holding the bow (whether adjusted for specific techniques needed in a piece, but also in a wider context depending on the training of the player.