3.1 Finding a Sonic Identity for Clara Iannotta’s dead wasps in the jam-jar (i)

In dead wasps in the jam-jar (i), Clara Iannotta extends the violin with three preparations – metal paperclips, a metal mute, and a metal thimble – that transform and destabilise the usual relationship between finger, string, and sound. The piece is based on the ‘Courante’ and ‘Double’ from J.S. Bach’s Partita No. 1 in B minor. The piece is divided in two, and as Tim Rutherford-Johnson notes:

- Each half begins and ends the same, with the two endings varied only in the type of sustained noise effect used: the first half ends with slow and heavy bow pressure, resulting in a broken, crackling sound; the second adds a series of tinkling, metallic scrunches produced by tapping a thimble on the strings.[1]

Iannotta found inspiration in Bach’s scalic runs, which here become glissandi and provide the piece’s driving energy. But the technique of the glissando turns from an action into an object, with fingertips and skin becoming a tactile eardrum for the performer, and, for me, somehow turns sound into touch. What seems like a glissando is instead an extremely fast succession of threaded nodes of the string “playing” the skin of my finger.

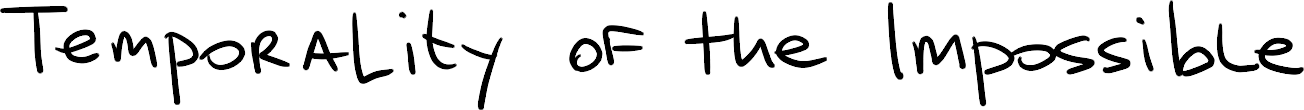

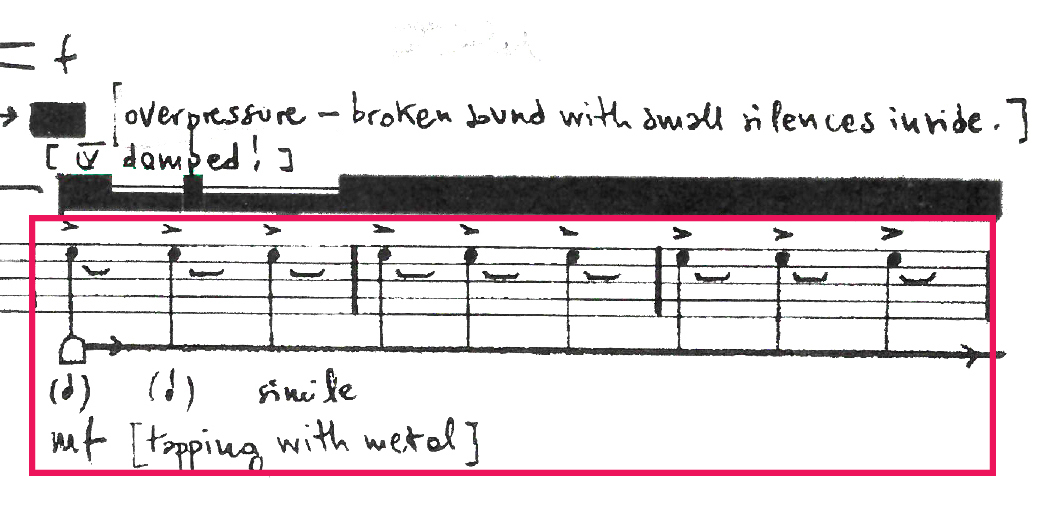

Looking at the score (figure 3.1.1), there is a clear starting and ending pitch connected with the line for glissando. Starting from the pitch for which the left hand has to be placed in a semi-position (located below the first position) and going to the highest possible pitch, this illustrates the longest distance of pitches on a string.[2] The harmonic pressure of the left-hand finger, AST mark for playing with the bow contact point on the far sul tasto side, and light bow pressure all evoke the potential of familiar sounding to come as a response to action. However, everything about this impression is a deception, as the instrument, altered with spiral metal paper clips preparation and use of the metal mute, gives a response nothing can quite prepare the ear for. Furthermore, Iannotta with the placement of the paperclips ‘reduce[s] the length of the strings substantially – from both sides’, drastically shortening the playing/sounding portion of the string and thus completely altering the range of the instrument.[3]

Figure 3.1.1: Clara Iannotta’s dead wasps in the jam-jar (i), first four bars of the piece (Interpretations, with reference: AP1, AP2.2, and AP3, can be found at https://temporalityoftheimpossible.com/research/artistic_portfolio.html)

I identified four main elements that contribute to the sound identity of dead wasps in the jam-jar (i):

- ■ Metal: preparation of the strings with spiral, metal paper clips; the bridge is covered with a metal mute; the little finger of the left hand has a metal tumble

- ■ Flesh: left hand in almost constant contact with the strings through continuous horizontal, glissando-like movement

- ■ Wood: bowing of the sides of the body of the instrument

- ■ Weight: different pressure of the bow, from very light to extremely heavy and change of pressure of the left-hand fingers.

The heavy metal mute is placed on the bridge before the beginning of the piece and is present throughout the piece.[4] Although the metal mute has a significant impact on the sound, it is the paper clips that are a crucial element of the piece, allowing Iannotta to construct a unique sonic identity that reflects and represents Iannotta's affinities for a very particular sound world and timbre.

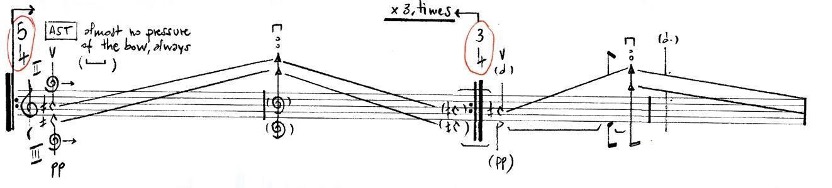

The type of preparation used on the strings are small, spiral, metal paper clips. The performance notes include both a diagram and a picture of the violin (figure 3.1.2) with the preparation.[5] The instruction reads as follows: ‘Put on the strings II – III – IV a small, circular, metal paperclip (see the picture).’[6]

Figure 3.1.2: Preparation of the violin [The preparation setting can also be seen in the video at https://temporalityoftheimpossible.com/research/artistic_portfolio.html, reference AP2.2]

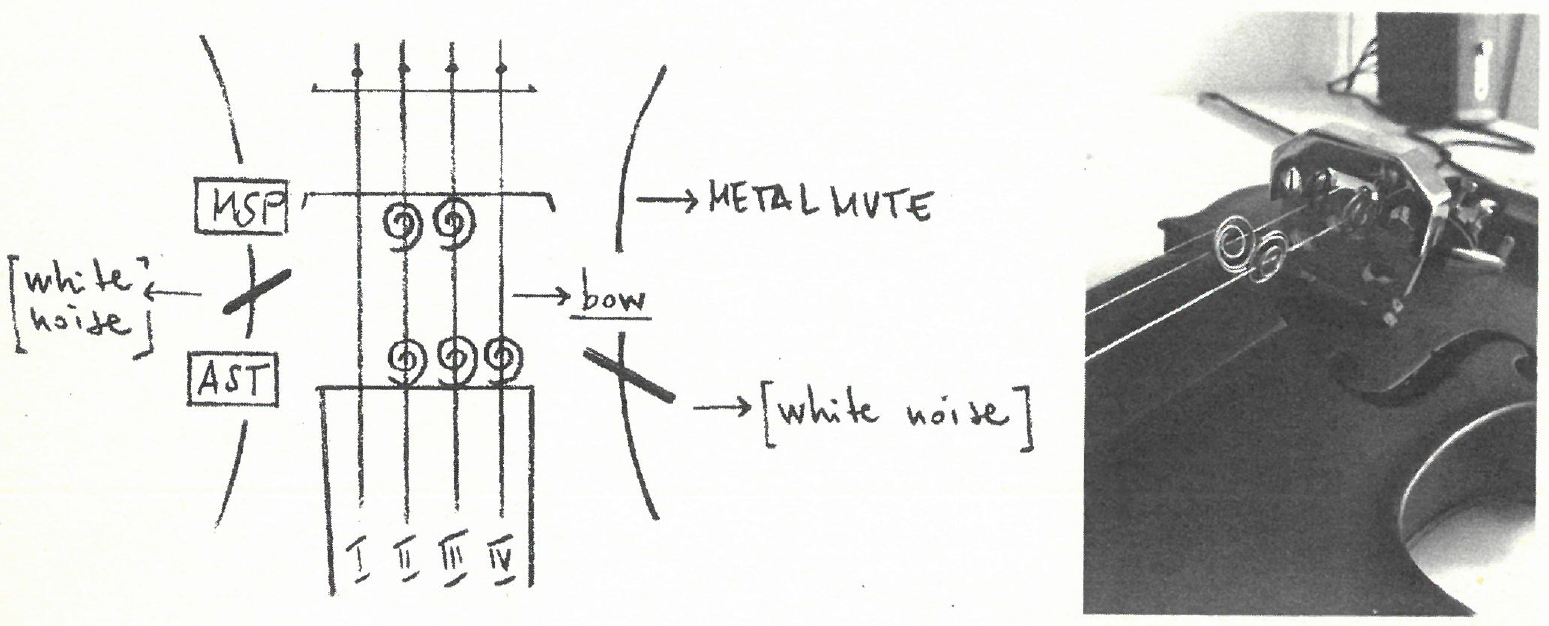

However, there is no mention of the diameter or brand of the paperclip, which proved to be important information. When I first looked for circular paper clips, a variety of diameters and metal finishes became an option. My choice fell on a diameter that was as close an approximation to what a “small” paperclip should be, compared to the photograph in the score. Since the photograph is not in colour, it was further difficult to estimate whether these were golden-, silver-, copper-finish metal paper clips. The initial paperclips I acquired were of 11.8mm diameter, with a set of silver and gold ones. Upon the first work session with Iannotta, the first point we addressed was the sound, the sonic identity of the piece, and specifically everything related to the paperclips.[7] Upon playing the first time with the instrument prepared with self-acquired material, it became clear that this is not the goal sound, and we discovered just how delicate and fragile this sound is. Before changing the paperclips to the ones Iannotta brought with her, we first tried moving the ones already on the violin, to check whether the placement was the issue. This didn’t improve the result much, so we made the switch to the right set of paperclips. Although very subtle, in an already subtle sound, the difference was quite clear. These spiral paper clips were of 13mm diameter and with copper finish.[8] This was not just a personal feeling of the sound, the difference was delicate, yet obvious and important. I took upon exploring the differences between the sets of paperclips. Besides the difference of the diameter and material, the weight of each of these groups of paperclips was different (figure 3.1.3).[9]

Figure 3.1.3: Process of measuring the paperclips on a digital scale

From my observations, these differences combined would pinch the string in a slightly different way, allowing for the vibration and the resulting harmonics to change (figure 3.1.4).

Figure 3.1.4: Differences in measures between the paperclips (sound samples can be found here: 3.1.5, 3.1.6, 3.1.7, 3.1.8)

As seen in the figure 3.1.2, three paperclips are to be placed just next to the edge of the fingerboard. Any object attached to the string (especially paperclips of any shapes/sizes), will, due to the vibration of the string, to some extent move on the string during playing. These specific spiral paper clips have proven through use to be less inclined to change place, and especially less likely to jump off the string, but they are not completely immune to it. The most vulnerable is the preparation of the IV string, which from experience, and experimenting, I found is best to place approximately 3,5mm further from the edge of the fingerboard.

The fact that this string and paperclip in particular are more sensitive is due not solely to the vibration of the string, but also to the combination of the left-hand finger pressure and right-hand bow pressure. From the total length of the piece, 100 bars, most of the piece is to be played by left hand touching the string as though playing natural harmonics. Bar 41 and the last 16 measures are to be played with dampened strings, which leaves only approximately 10 bars that ask for normal, full finger pressure.[10] The first appearance of the full pressure of the left hand is in bar 11. Placing of the paperclip on the fourth (G) string 3.5mm further away from the edge of the fingerboard becomes increasingly important with the fact of this finger pressure so early in the piece. The bar is also the first bar where the bow pressure will change from light, almost no pressure, to normal pressure. As the left-hand finger presses the string to completely block it against the fingerboard and the bow is from the other side also pushing the string in the downward direction, the string comes close to the fingerboard in the area where the paperclip is. If the paperclip is placed too close to the edge of the fingerboard, this proximity to the fingerboard will push it off the string. Two other practical aspects to take care of for more secure setting are that the paper clips close to the bridge should not touch the metal mute and the outer open ends of the paper clip should face away from the bowing area. The first aspect allows the paper clips more freedom in vibrating, the latter is to diminish accidental tearing or entangling of the hair of the bow within the spiral (figure 3.1.9).

Figure 3.1.9: Practicalities for setting up the preparation in Clara Iannotta’s dead wasps in the jam-jar(i)

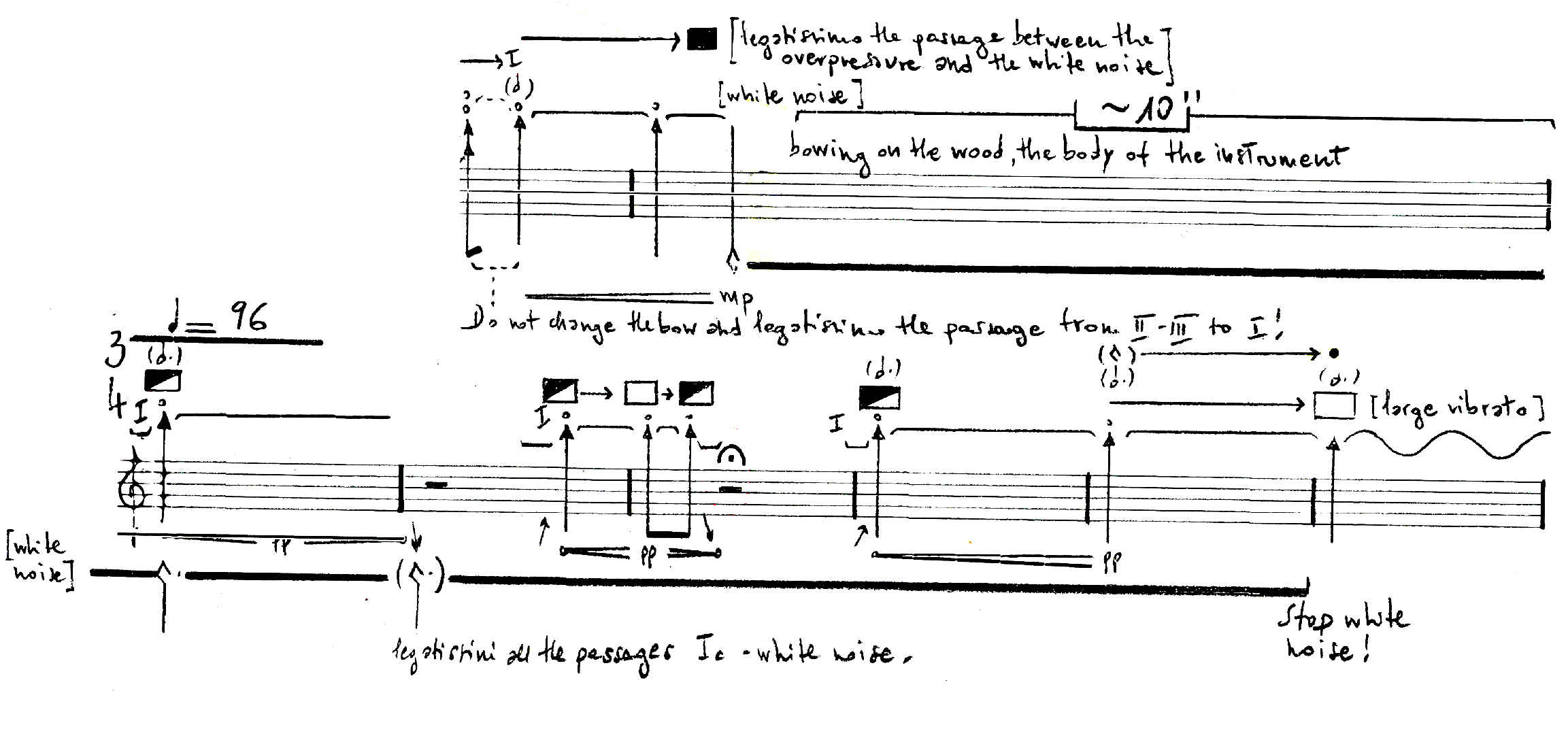

Even in the event that this moment in the piece does not push the preparation completely off the string, any amount of moving it up also can destabilise the balance. There are two aspects where balance must be carefully considered here. One is linked to the placement of the paperclips for achieving a specific delicate sound and the other is the balance of physical interaction between the string and the paperclip. Displacement of the paperclip will make for more likely further twisting and eventually falling off of the paperclip from the string. With this event being so early in the piece, this can have undesirable consequences for contrasts that are to come. Most notable is the fifth appearance of this motive in bar 37. This moment comes little over a third into the piece, after overall pp and p dynamics, with only short instances of more than normal pressure (but still in p dynamic) to mp dynamic. With full left-hand finger pressure, greater than normal bow pressure and a crescendo at the end of bar 40 leading to f, this is not just a musically turbulent moment, but can also be a minor physical shock for the altered instrument, and its delicate preparation. The next bar, bar 41 (figure 3.1.10), brings the most severe overpressure, with a very granular texture. This effect is achieved with “plucking” of the string with the bow, with extreme vertical pressure controlled by the index finger, while continuing the horizontal movement (figure 3.1.10). Each grain of noise in this moment is a kind of shock to the paperclip, and it is very likely it will move more drastically. In addition to precaution with placement in relation to the fingerboard, here the left hand can be of help: while keeping the string muted, the finger should “push” the string to counter the pulling force of the bowing, thus neutralising to some extent the shock, and making the paperclip more likely to stay in place (figure 3.1.10). On the practical side, it is also important to keep in mind that paperclips lose their strength and grip, and should be regularly replaced with new ones.

Figure 3.1.10: Listening and responding to the altered physicality of the instrument in Clara Iannottaa’s dead wasps in the jam-jar(i), excerpt: bars 35 to 41

The final element of preparation used in this piece is a metal thimble, which is to be placed on the little finger of the left hand (figure 3.1.12 and 3.1.13). The performance notes indicate the thimble to be placed on the fifth finger. Although technically correct as the thimble is to be placed on the little finger, in violin markings this finger is usually referred to as the fourth finger.[11] Since the piece has no pause, the thimble is to be on the finger throughout the piece, making this finger exclusively usable only for the actions requiring the thimble: bars 58 to 62 in combination with white noise produced with bowing on the wood body of the instrument, and 85 to 100 in combination with the overpressure motive (figure 3.1.11).

Figure 3.1.11: Bars 85 to 87; thimble and overpressure

Having the thimble on the finger throughout does not create any particular inconvenience, as the first, second, and third finger are sufficient for playing everything else in the score. With small adjustment to fingering of the artificial harmonic, first appearing in bar 34, pressed first finger should be combined with the third finger with harmonic pressure, instead of a more common fourth finger. Slight extension of the finger, thus providing more flesh, further aids the desired ‘very bright’ colour.

Figure 3.1.12: Close-up of the metal thimble on the finger holding the instrument prior playing; still from video available in https://temporalityoftheimpossible.com/research/artistic_portfolio.html, reference AP2.2

Figure 3.1.13: Finger with the metal thimble in action (bar 58 to 62); still from video available in https://temporalityoftheimpossible.com/research/artistic_portfolio.html, reference AP2.2

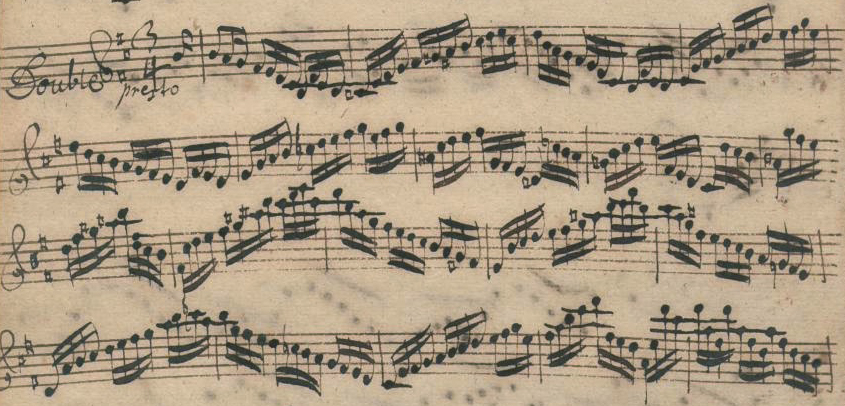

When speaking about the inspiration for the piece during our working session, Iannotta explained that, once she started thinking about the ‘Courante’ and ‘Double’ from Bach’s Partita No.1 in B minor, she started imagining what would happen if these scalar passages (figure 3.1.14) going up and down would be played at first normally and then faster, and faster, and faster. And thus, the left-hand material arose from the speed of moving up and down, represented as glissandos in Iannotta’s notation.

Figure 3.1.14: excerpt from J.S. Bach’s Double from Partita no.1 in B minor[12]

Thinking and trying out Bach’s ‘Double’ (BWV 1002) – going from normal, then fast, then faster, then even faster … playing as fast as possible … playing so fast that it must become legato … then even faster – I arrived at Iannotta: a glissando which is not a glissando but a condensed time-space, a continuous line composed of thousands of “grain-notes”, that the mechanism of human fingers cannot quite achieve yet they exist. Iannotta confirms the validity of this approach, stressing on multiple occasions that this movement ‘is not a glissando’.[13]

Figure 3.1.15: Close-up of a violin string

I conceived the idea of inverting the roles of string and finger. Violin strings have a final coating as a thin winded layer, where each of the connections in the winding process becomes like a little node point (figure 3.1.15). If the fingers cannot play that many notes in that fast speed, and the hand must move in a gliding way up and down manner, this movement of the hand touching the string along the way becomes the “string” and each of these node points on the string is a fingered note playing the path of the finger. This approach, for me, unequivocally influences the affection with which finger touches the string as well as the movement as a whole. Once my mindset was placed in this state, it was easier to really start working on the piece, explore the potentials and aim for this timbre of flickering texture that is simultaneously a continuous sound.

Finally, characteristics of the metallic, trembling sparkling continuous sound and the heavy pressure grains are complemented with wind, breath-like vacuum, a white noise sound that is achieved by bowing on the wood of the body of the instrument (figure 3.1.16).

Figure 3.1.16: Bars 23-28, first appearance of bowing on the body of the instrument

- [1]Tim Rutherford-Johnson, program notes: dead wasps in the jam-jar (i) (2014-2015) (2018) http://claraiannotta.com/works/solo-works/dead-wasps-in-the-jam-jar-i-2014-2015/ [accessed 24 May 2023].

- [2]Triangle noteheads of the note in the second bar of the figure 3.1.1 indicates the highest possible pitch on the violin.

- [3]Clara Iannotta, Composer Talk: Clara Iannotta (online event organised at https://www.lineuponlinepercussion.org/, 25 September 2020).

- [4]Heavy metal chrome-plated mute, also known as “hotel mute”, of kind such as offered in GEWA or TONEWOLF catalogues.

- [5]Including an image, or multiple images, of preparation is not isolated to Iannotta’s practice. Robert Wannamaker includes as part of the score package images for each movement, as well as any in-movement possible crucial point. The inclusion of images can be seen not only as an aid to explaining the preparation of the instrument, the augmented technology of the instrument, but also a preparation for the imagining of the sound while looking at the score. John King, for his piece Four Études for Prepared Violin from 1982, does not provide a score. The piece consists of the photograph of an extensive preparation, accompanied with a recording of King playing a version of the piece. The performer is to decipher four areas which they themselves are then to explore and build into a performance length piece.

- [6]Clara Iannotta, dead wasps in the jam jar (i), for solo violin. Edition Peters. EP14268 (Berlin: Edition Peters, 2014-2015).

- [7]The session took place on 6 December 2017 in Huddersfield.

- [8]The exact paper clips used are by Creative Impressions, they come in a packet of 25 paper clips, and the brand’s reference is “Antique & Copper Mini Spiral Clips (25) ITEM 84999”

- [9]The weight was measured using the digital type of scale.

- [10]The finger pressure is indicated with an empty diamond symbol for harmonic pressure and a completely colored small circle, a bullet dot, for use of full pressure.

- [11]Thumb is rarely counted as a “playing” finger, thus the counting starts from the index finger. If thumb is to be employed, it is mostly found in notation with reference to ‘thumb’. Or as in the case of Buccino, with a specifically assigned symbol.

- [12]Bach, Johann Sebastian, Partita no.1 in B minor (‘Courante’ and ‘Double’), in Six Violin Sonatas and Partitas, BWV 1001-1006. Manuscript, n.d. Copyist: Anna Magdalena Bach, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (D-B): Mus.ms. Bach P 268 (ca.1725-34)

- [13]This was shared by Iannotta in our first work session on 6 December 2017, but also on three later occasions, one of which was on 25 November 2018 in Huddersfield.