2.2 Locating Imagination: tactile sensorial conception of the unheard

‘Sound is intrinsically and unignorably relational: it emanates, propagates, communicates, vibrates, and agitates; it leaves a body and enters others; it binds and unhinges, harmonizes and traumatizes; it sends the body moving, the mind dreaming, the air oscillating. It seemingly eludes definition, while having profound effect.’ – Brandon LaBelle [1]

To imagine a score, a performer must conceptualise music from written text preceding its actual sonic-auditory experience. Reading and hearing music is 'never a simple matter,'[2] and in this section I will concentrate on conceptualisations of sound through their possible pre-gestural tactile experiential states. While I introduce the conceptual process of thought behind the topic of imagination and imagining of the sounding of scores mainly using examples from Dario Buccino’s Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, Liza Lim’s The Sun Song Star Map, and Rebecca Saunders’s Hauch, in chapter 4.1 I further elaborate on clarifying sonic identities through and in practice. Works by Saunders and Lim might seem “simple” to imagine in conventional ways but they turn out not to be, and the sounding of Buccino’s piece is unimaginable in common conception. As such, I chose these three pieces as they are three distant but connected points that create a space in which this way of thinking about imagining sound can be presented, and from which one can continue to develop.

The idea of expanding the pool of associations used as a source for imagining arose from the need to find complementary paths to the more habitual temporal, pitch-gesture driven, and multifaceted cues found in the score. Any written musical score carries information that enables the performer to imagine in the interplay between location, gesture and sensation; where “location” signifies the place on the instrument where the specific pitch is obtainable, “gesture” is the actions made by the left and right hands in relation to this location, and the “sensation” is the spectrum of tactile sensations of sound that the body can feel. In western European notation, with precisely given location combined with duration, the initial and relatively truthful imagining of the outcome from the notation itself is possible. In this trajectory, triggers for imagination arise from location-gesture-sensation order. In pieces by Dario Buccino, Aaron Cassidy, Clara Iannotta, and Liza Lim, on the other hand, this base is challenged, and the need for thinking in sensation-gesture-location became, in my experience, a crucial element for playing the pieces. In this pursuit, the question becomes how to feel a sound that has not been heard before (and might not ever be repeated) beyond turning to habitual forward-motional, path-like, and visual-imagery metaphors for guidance.

Deciphering composers’ intentions and describing the desired sound outcome in the process, and subsequently the actions required, utilises metaphors from everyday language. Adlington concludes that ‘metaphor is not simply a feature of verbal description but is actually fundamental to the way in which we experience the world,’[3] closing his argument with a citation from Lakoff that ‘focus of metaphor is not in language at all, but in the way we conceptualise one mental domain in terms of another […] Metaphor is fundamentally conceptual, not linguistic in nature.’[4] Vocabulary used to express qualities of sound often comes through words borrowed from the visual epistemology: colour (bright, dark, light), or, for example, in violin playing the “shaping of the sound,” referring to imagining sound and the actions of the hands. Adlington speaks of metaphors that are often used for describing music that include terms such as ‘brightening, softening, swelling, floating, heating-up, explode,’ and argues that these descriptions provide instantly recognisable change when experiencing music.[5] In performance notes for The Su Song Star Map, Lim describes some of the desired sound distortions as “husky” and “throaty”, following with that ‘all distortions are of emotional type…or a veil of whisky and cigars over the sound,’[6] and Cassidy uses terms such as ‘fragile, splintered; crackling; explosive, wild; frenetic; fragile, fractured.’[7]

The descriptions offered by composers are invaluable guidance in the process of building an interpretation regardless of which area of experience and sensorial epistemology the terminology is drawn from. Thus, a performer can choose to position their departure point for imagining to be ‘the self-defined in terms of hearing rather than sight’ as this self is ‘imagined not as a point, but as a membrane; not as a picture, but as channel through which voices, noises and musics travel.’[8]

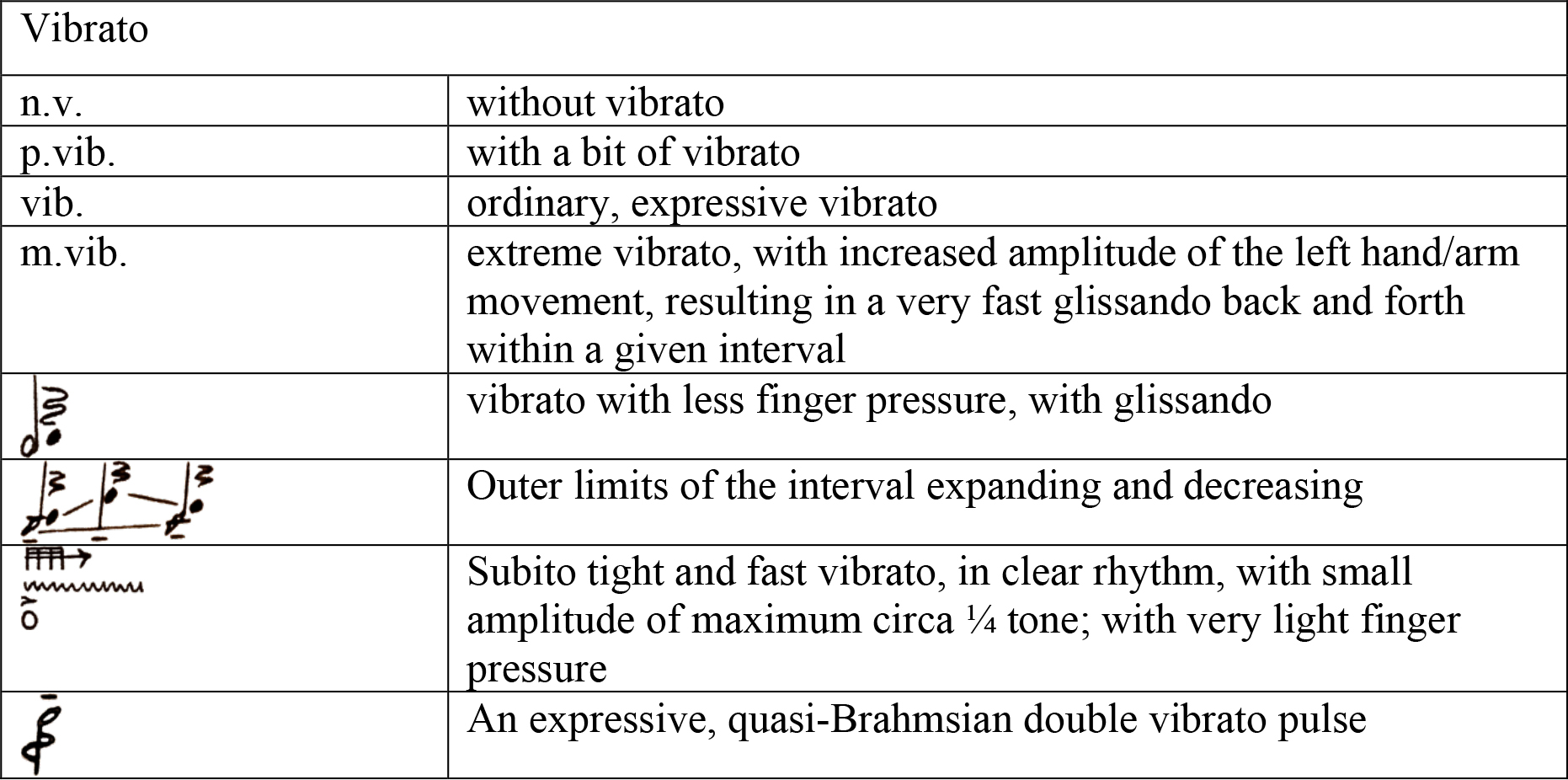

Within all its complexity, our hearing starts from a physical sensation of vibration of a membrane within our body, so this is a tactile sensation. Evelyn Glennie, a profoundly deaf percussionist, talks about hearing in terms of touch, and hearing through feeling the acoustic vibrations in body parts that go beyond just the ear.[9] Taking a cue from this model, I more consciously started to approach imagining the unheard sound through tactile-felt thinking, intercepting and giving a second plane to the otherwise dominant visual-imagery or relating to pre-heard concepts.[10] When it comes to the experience of knowing through the modes of five external senses, Cox describes knowledge gathered from the sense of touch as ‘understanding is grasping’, as knowledge that comes from ‘physical investigation of objects, and this involves the power of the hand’[11] or tongue.[12] What I became interested in through my repertoire is perceiving the body of the performer as “the object” and sound as “the hands” that are touching. By inverting the starting point of who is the observer and what is the observed in sensing and understanding the vibration of the sound, the knowledge gathered is shifted to the very action of vibration of the sound, and, subsequently, its materiality and physicality, even when movement of the body is microscopic.

When it comes to the music I have focused on in this project, there is a rupture between how something is written and how it will sound. To imagine the sounding of this music-conveying text is to conceive a physical sensation of vibration before that vibration has ever taken place in the physical world. Unlike with more conventional scores where it is common to use the instrument already in the first reading, the first reading of these pieces requires a more focused and abstract process of imagining isolated from instrument and playing.[13] For a substantial portion of the violin repertoire, there is a basic reliance on the pitch and duration properties of the music, the “note”, that can be delineated from the score. There is also a considerable reliance on the memory of the sounds previously heard or made. With this in respect, even if not heard before, there is a plausible starting point from which an unheard score can still be conceived in the mind of the performer. In pieces with the surplus of layers and information, this initial processing becomes especially beneficial to understanding and creating a departing point and context.[14] With this kind of approach, there is an opening for metacognition to enter the next step that involves multilayered processing of cognitive and physical actions. As one endeavours to have meaning ‘created through senses beyond the traditionally privileged one, vision,’[15] a more critical approach is needed for imagining sound, as the intermediate structure between the score and the performance. How might one start to imagine phenomena that are physical but not necessarily recognisable by the eye in the notation?[16]

When working on these pieces, situating when and where one starts this process of imagining was of crucial importance. Jerrold Levinson’s definition of musical work as a ‘compound or conjunction’ that consists of two structures: a sound structure and a performing-means structure,[17] offered a frame within which I embedded the third structure, the imagining. In becoming of the musical work, bringing the music from the ‘first space’[18] into the physical space, imagining stands as a transitional structure: conception of the sounding result as a complex system of thought and physical actions and interactions between a performer and their instrument. It is a transitional structure because the process of “imaging” is one of the elements towards the performing-means, yet its trajectory is not unilateral. The performing-means structure can return information to the conception and imagining, and in doing so further expand the understanding of the sound structure, creating a necessary feedback loop. The imagining of sounding belongs to both abstract and tangible worlds. It is abstract to anyone outside of the body of the performer, but it is a tangible world within the performer and body as the tactile sensory field. The more conventional, pitch-led gesture embodied knowledge deals with touch and weight as an addendum, providing timbral nuance to a note. The way of pressing and depressing the finger on the string, using the weight of the fingers or hand, right hand and bow pressure and contact, are all the elements the violinist evaluates and includes in repetition and practice.

Philip Thomas speaks about the tactile aspects of playing and sound, but again as something that comes after the initial conception, in the quest for building upon a specific pitch with all its desired timbral nuances. The effect of such care for the touch is audibly noticeable especially in Thomas’ interpretations of Morton Feldman’s piano music.[19] Thomas writes, ‘when I see a note within the context of Feldman’s music, I have a sense of action, or movement, and of touch. This is less a form of synaesthesia than the inevitable product of a prolonged and regular engagement with the music.’[20] Pianists’ “tactile conception” of sound is not only about the gesture that they have to make, but also the response of the instrument that will turn this touch into the sounding result; no matter how much control the pianist has, there is a high probability for different sound, simply because it will literally be produced by a different instrument.

Although a violinist will repeat actions in the same manner and on the same instrument, the unpredictable nature of the pieces under discussion here will also have a threshold of unpredictable return of sound. Approaching the conception of tactile sensation as something that precedes the experience of the sound and the movement that produces it allows for “reversed” direction, in which the feeling of the sound goes to become sonorous (through technique of playing).[21] But just like the pitch-duration driven conception of sound and movement, this touch-imagination can be adjusted and refined upon the experience of the result through practice. In a conversation, Thomas, responds to this thinking with ‘yes, when I play on a different piano, there is the imagination of how do I touch the key, but the outcome due to different instrument might/will not be the same…,’[22] but the importance of touch and tactile nevertheless remains a crucial and important aspect. In his approach to playing Feldman, Thomas also draws attention to the materiality of sound as,

- having a basis in some deep and sensuous contact between flesh and instrument. At the same time, for me it also has to do with the action prior to contact – how I lift my hand, my wrist, the sensation in my arm, the degree of tension felt, the balance of control and suppleness in my fingers, the angle of my finger as it approaches the key, the combination of finger-tip and finger-pad, the degree of finger lift before the contact, the velocity of the attack. ALL of these things are part of my conceptualization of the sound in response to the notation. This complex set of configurations, each speaking to each other in mysterious ways, point to what I feel is the complex nature of the sound-world, none of which has anything to do with dynamics, other than that they would have very different meaning were they within the context of dynamics other than ppp.[23]

In music whose essence is not primarily based in the note but rather in mixtures of timbre and gesture, the tactile pre-conception of sound is necessary research for intentionality that starts from the inverted departing focus. The sensation and thinking in the form of sensed vibration allows for further developing intricate systems of imagination through how the sound feels rather than how it sounds. On the violin, the finger and the string are in direct contact without any intermediary object, allowing for direct contact and reaction to be captured and internalised. Just like “regular” hearing of a ‘score in print and playing it are of course worlds apart,’[24] this hypothetical tactile sound palette does not exist without practice and exploration. It is in this respect the same as its mirror action that seeks to obtain a pitch. This is where the feedback loop practice enters, and through experiences gathered through trial, self-analysis, and repetition the pool of tactile-sensed sound references is expanded and becomes available to be called upon as “information” that aids future conceptions (imagining). This process was for me specifically valuable as a path to bridge the gap in dealing with the unexpected and uncontrollable that arises from directions composers are taking.

In Rebecca Saunders’ >Hauch I found a balance between that “regular” (with its demands from the left hand) and the undefined exploratory world (though abstractions it demands for the right hand). The piece has a strong note (pitch- and duration-)base, which provides for much information that then grounds left hand-related sensations (and actions) to be guided with clear directionality. The name of the piece itself sets a particular environment: hauch is a German word without an exact English translation, for which Saunders lists a selection of possible meanings: ‘a trace, touch, hint, tinge, soupçon, tang, wisp, or a breath of something.’[25] She further explains that the word ‘implies a suggestion or intimation of the thing: a shadow, an aura, a glimmer hidden beneath the surface.’[26]

The piece follows a two-part melody line whose fragments appear and disappear in silence through eight clearly marked segments. There is no time signature, but the proportions and duration are firmly embedded within the staff line's graphic spatial organisation. Looking at first at the notation of this piece, it is possible to roughly conceive a departure from the notation itself (primarily relating to the pitch and duration), but the exceptionally nuanced and fragile sound and timbre demands extensive exploration for the performer.[27]

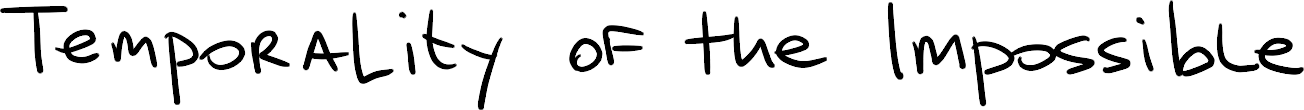

Figure 2.2.1: Example from Rebecca Saunders’ Hauch (2018) for solo violin

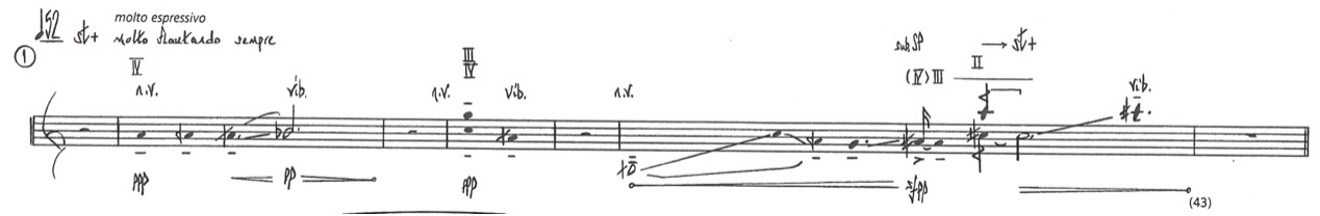

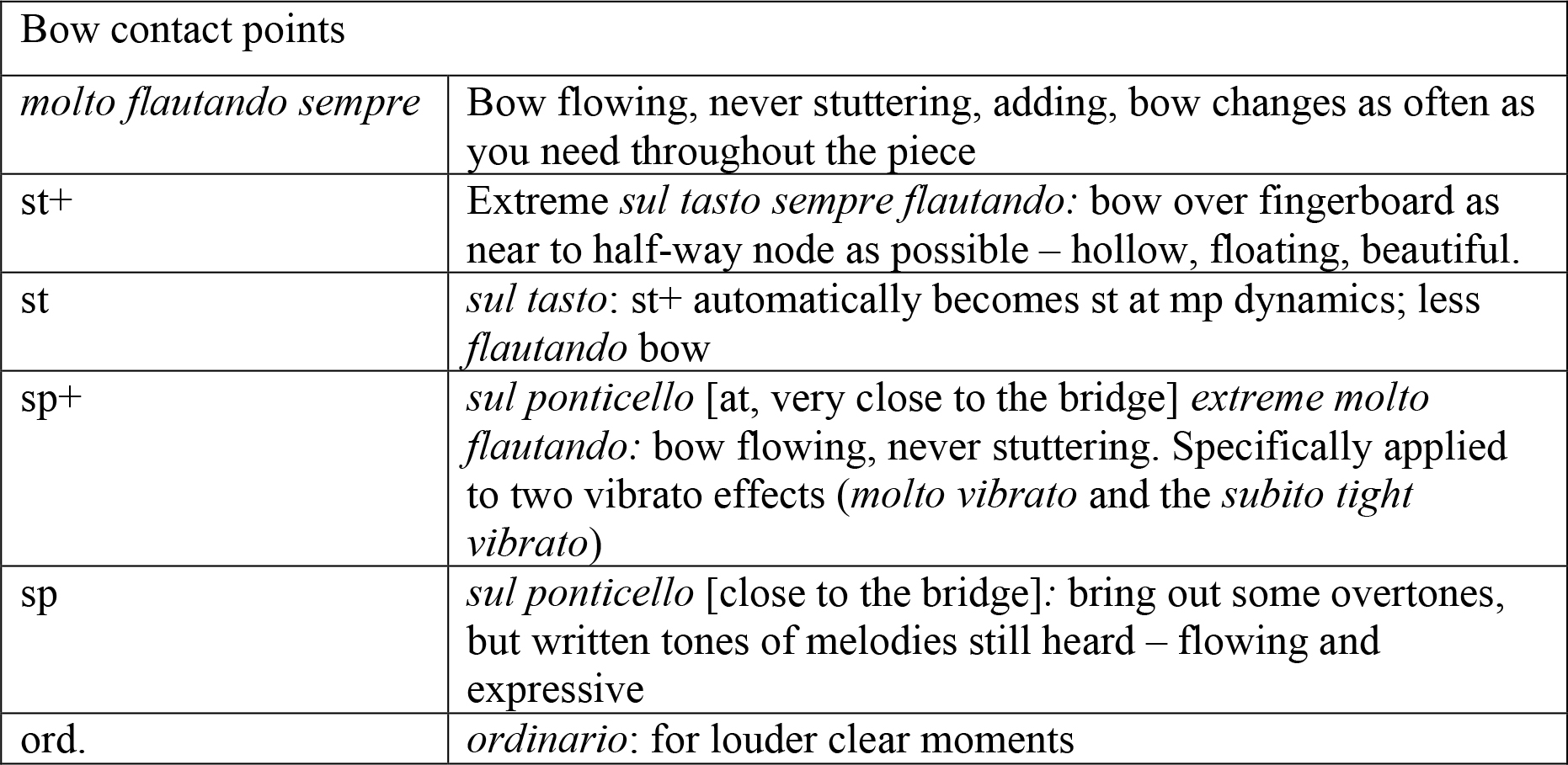

Figure 2.2.1 shows the first of eight segments from the piece. Beyond pitch (and pitch alterations), duration, dynamics, and articulation, Saunders gives great detail and care for vibrato and placement of the bow. The legend differentiates five bow placement degrees (figure 2.2.2), with emphasis on the general remark for the “molto flautando sempre,” and eight types of vibratos (figure 2.2.3).

Figure 2.2.2: Bow contact points in Rebecca Saunders’ Hauch

Figure 2.2.3: Types of vibratos in Rebecca Saunders’ Hauch [28]

In the notes for the performer, Saunders gives a detailed description of general aspirations in how to think about time, timbre, and colour. There is even a very specific recommendation to ‘Try practicing st+ phrases just once with a wooden mute! – to hear the fragile dark st+ timbre you need to aim for.’[29] The atmosphere, the repeated use of extremes, emphasising fragility, the coming in and out of silence, it would be easy to start thinking within a much wider spectrum, wider threshold of veiled, hidden sound that would disorient the sense of its origin being a violin. Although the piece sets the performer on a quest for surfacing in and out of silence, examining timbre in high positions, having pulsations from vibrato wideness, in a rehearsal Saunders confirmed that these sound worlds are all still to remain within the realm of ‘just a regular [recognisable] violin sound.’[30] The Notes to the Performer detail clearly and to the point that a score should be read through the prism of the “standard” sound. The timbre and possibilities in the high positions of the lower strings remain to be explored and sound-constructed, but the outcome is to remain within the realm of the soft, (extreme) piano sound, never bringing in doubt that the source is the violin. All these pieces of information clearly suggest that the tactile has to be placed second behind the clear pitch-gesture as a departure for the construction when it comes to the left hand. However, the ideas of imagining through the prism of tactile that is beyond the common are already present in the guidance Saunders’ outlines for the right hand.

What is perhaps the most provoking thought about the work is not written in the notes to the performer, but in the programme notes:

- ‘Hauch is a solo study exploring pianissimo timbral nuances at the top of the lowest violin strings; tracing fragments of melody, drawn on a thread in and out of silence.

Surface, weight and touch of musical performance: the bow drawing the sound out of silence; the slightest differentiation of touch on the string; the expansion of the muscles between the shoulder blades; the player’s in-breath preceding the played tone … The fallible physical body behind the sound: feeling the weight of sound, exploring the essence of a timbre.’[31]

Although Saunders does not ask Hauch’s performer to explore the extremes of sound and silence beyond what will be recognised as violin sound, the imagery given by the composer in the notes which insist that the attention should be paid to ‘the slightest differentiation of touch on the string; the expansion of the muscles between the shoulder blades’[32] does flirt with the idea of tactile conception as the initiator of ways to imagine.

While still anchored within the commonly imaginable abstraction required from the right hand, and to some extent through specific use of vibrato for the left hand, moves Hauch to the undefined world and as such is a step toward the intentional disconnection from common empirical conception and imagining. In my practice, Hauch, together with other specified pieces, offered the kind of a positive provocation that led me to search for what happens when the solutions are initially even less clear.

To an extent, Liza Lim’s The Su Song Star Map is another piece conceivable from a pitch-duration point of view from reading the score. However, with scordatura, intricately nested and interlaced repetition, and multiphonics, this piece too becomes one that exuberates intentional instability and unpredictability. One of these moments can be seen on page 15 (figure 2.2.4).

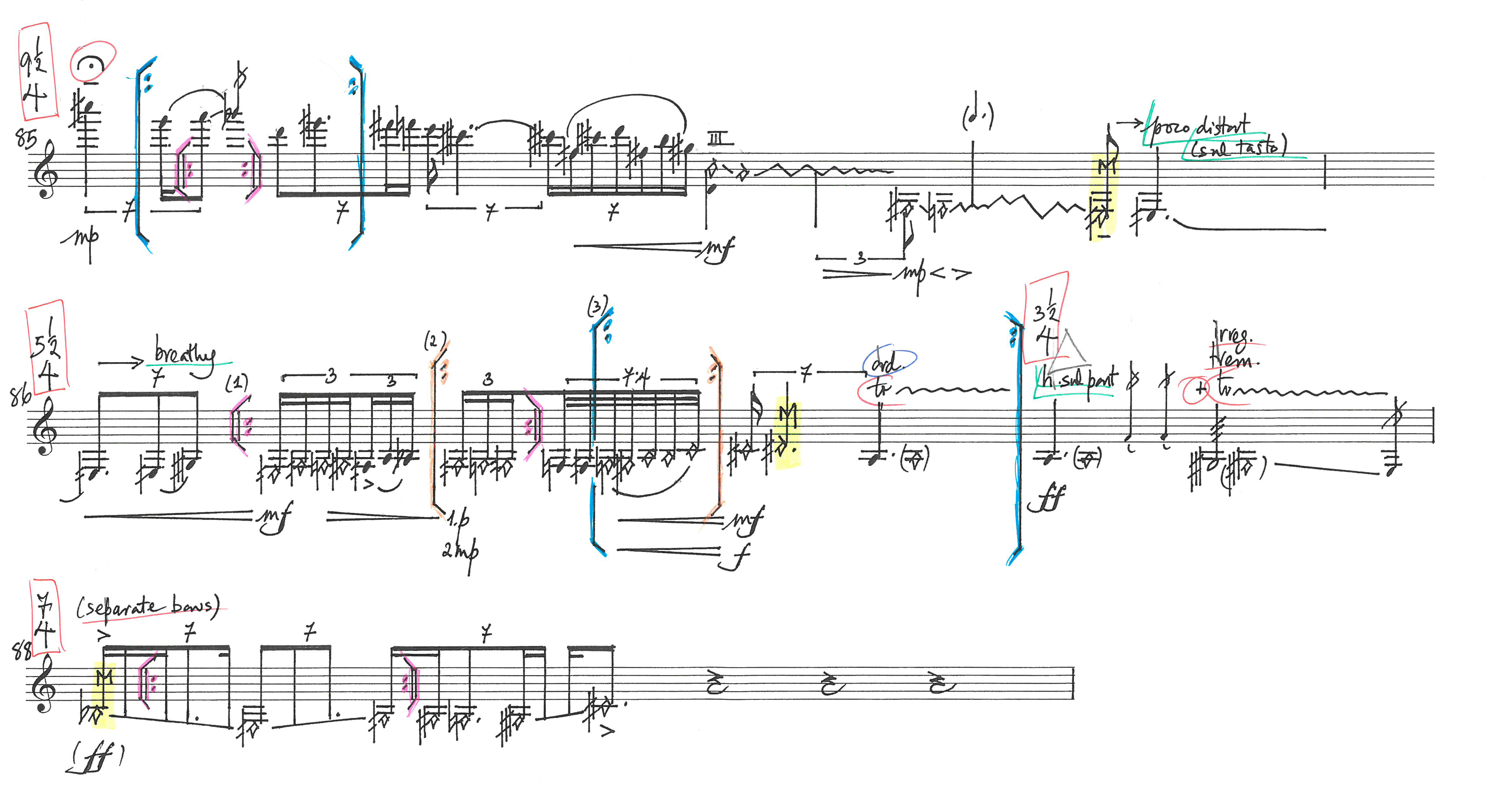

Figure 2.2.4: Liza Lim’s The Su Song Star Map, manuscript, page 15, annotated by the author

The essence of this section is not only in the timbral information conveyed in the notation, but also in the unique, intentionally unrepeatable and desired instability of a collection of the sounds that multiphonics and other non-standard harmonics create. The fast succession of changes between the harmonics and multiphonics, as well as interlaced repetitions, all contribute to each performance ultimately having a unique outcome. Different, fully or lightly[33] depressed actions of the finger in order to achieve them have the intention to create a flowing line, or as Lim writes in the performance notes, ‘a fluid “3-dimensional” quality as one rapidly shifts across different timbral spaces’.[34] Added to that the various timbral directions (noted as breathy, husky, poco distortion), there is an exceptionally palpable richness of sound that arises. To reduce building of this complex sound architecture to execution that relies only on pitch-location of the finger seems almost irresponsible. Here, the practice and loop-feedback cycle become much more rewarding for the performer and for the piece when care is placed on the tactile-imagining, at least in equal amounts to “standard” practice of action.

In pieces with ample information (Buccino, Cassidy, Johnson, Lim), whether asking for extreme timbral (Buccino, Iannotta, Johnson, Lim) or gestural explorations (Buccino, Cassidy), the basic challenge of how to imagine each element on its own, is further intensified by the impossibility of predicting how parameters react when they are combined. Further to this, the very legibility of notation can be challenging. Here it is possible to talk about two different strands of challenges. One, where the outcome in reference to the type of notation used seems easily imaginable, yet it is contradictory to the actuality of its intended sounding (Cage, Iannotta, Lim, Johnson). And the second, where the notation is very composer-language-specific, and with that even piece-specific, so that referencing any already experienced music, sound, and works is only vaguely applicable (Buccino, Cassidy). These strands interlace. In dead wasps in a jam-jar (I) (Iannotta), The Crutch of Memory (Cassidy), and Finalmente il tempo e intero no.16 (Buccino), neither pitch and hearing with the inner ear are any more reliable as a starting point, nor is the gesture related to it.[35] Repetition and practice over time will build more appropriate reference points and more accurate anticipation and reaction to what could be misinterpreted in the moment of the performance as mistakes or deviations from the truthfulness to the score.

Establishing an embodied experience for a particular sound, the various out-of-the-body (of the player as well as of the instrument) influences can greatly affect the outcome. However, the threshold of improbability for absolute control of accurate response of the instrument to the action made to produce a sound remains extremely low and unstable due to manyfold demands to be applied simultaneously, each carrying its own instability. It is this multiplication of instabilities that results in pitch-gesture relation to lose on its status as provider of certainty and reliability and opens the space for abandoning privileging them ‘over the other acoustic auditory features.’[36]

Another reason that aiming for that reliable geographical[37] distance, the relation between pitch and duration and hand-movement-feeling as source should be avoided is that established gestural comfort obscures the instability and fragility that are important aspects of the auras of these pieces. In this context, relying on the recordings of previous interpretations as a source for initial conception can even be deceitful, as crucial parameters and determinants of pieces (such as preparation of the instrument or gesture that is determined by the physical properties of the hand of the performer) make for different possible “truthfulnesses.” The piece dead wasps in a jam-jar (I) uses preparation, and slight inconsistencies in placement of this preparation will result in a different sound.[38] Using gestures as musical material, The Crutch of Memory is dependent on physical characteristics of a hand of a specific player, thus again leaving room for greater oscillation in sounding as related to pitch.[39] It is of an extreme importance not to seek inspiration by simply listening to an interpretation, not of other but also not of self.

According to recent theoretical studies,[40] ordinary sound waves carry a small amount of mass in them. The research in the measures, effects, and physical interpretation of the mass flow is still ongoing,[41] but this scientific discovery is attractive for musicians as it adds to the repertoire of features and aspects of sound a performer can consider in the process of imagining. If sound has a mass and a gravitational field of its own, even if they cannot be registered by human perception, this information and property becomes an element in the process of imagining that can be linked to tactile and felt. Instead of imagining how the sound sounds, a performer can imagine how this sound feels when the body is being touched by it, for the performer or when passing and landing close to the audience.

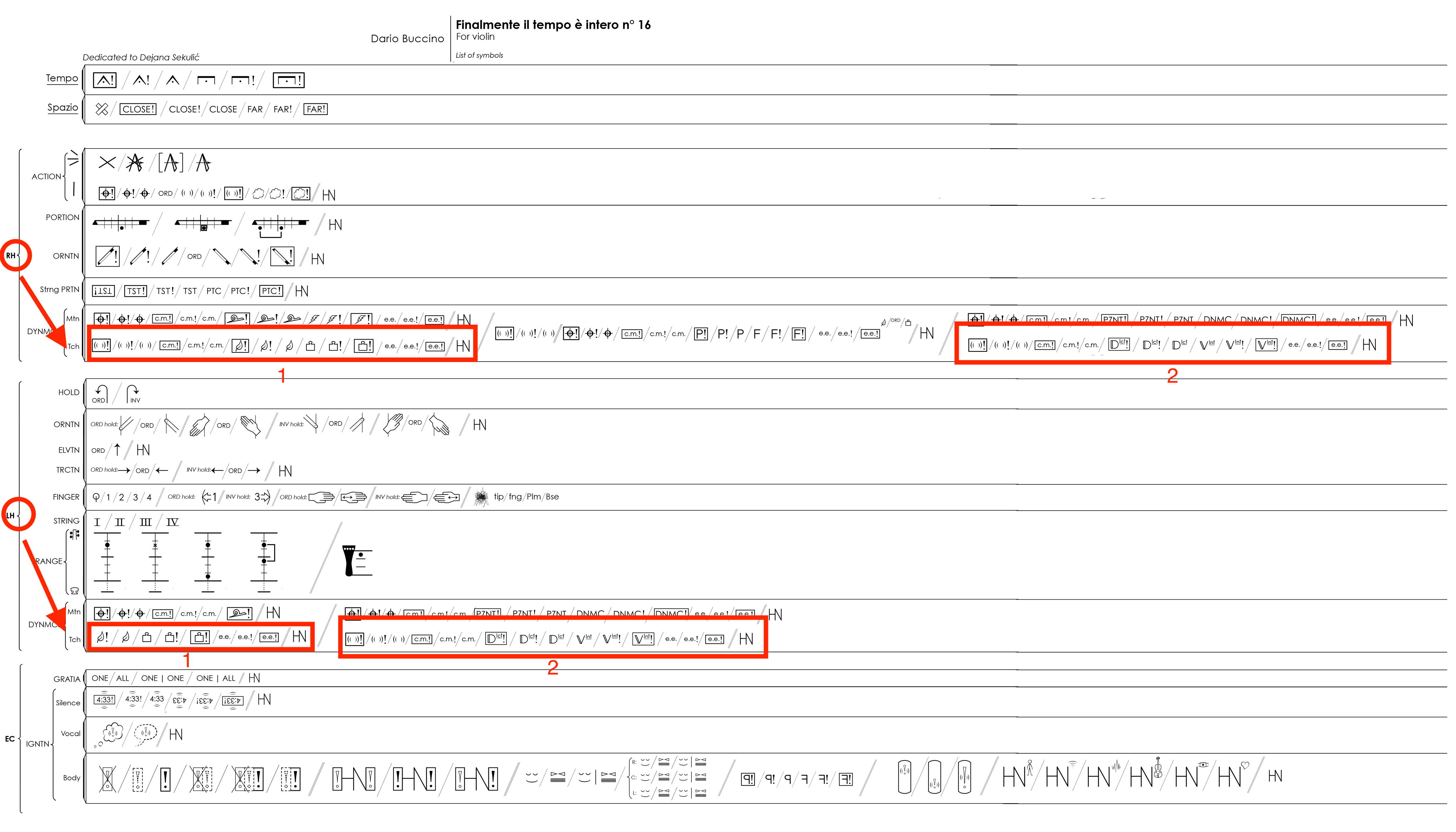

Figure 2.2.5: Dario Buccino’s Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, list of symbols

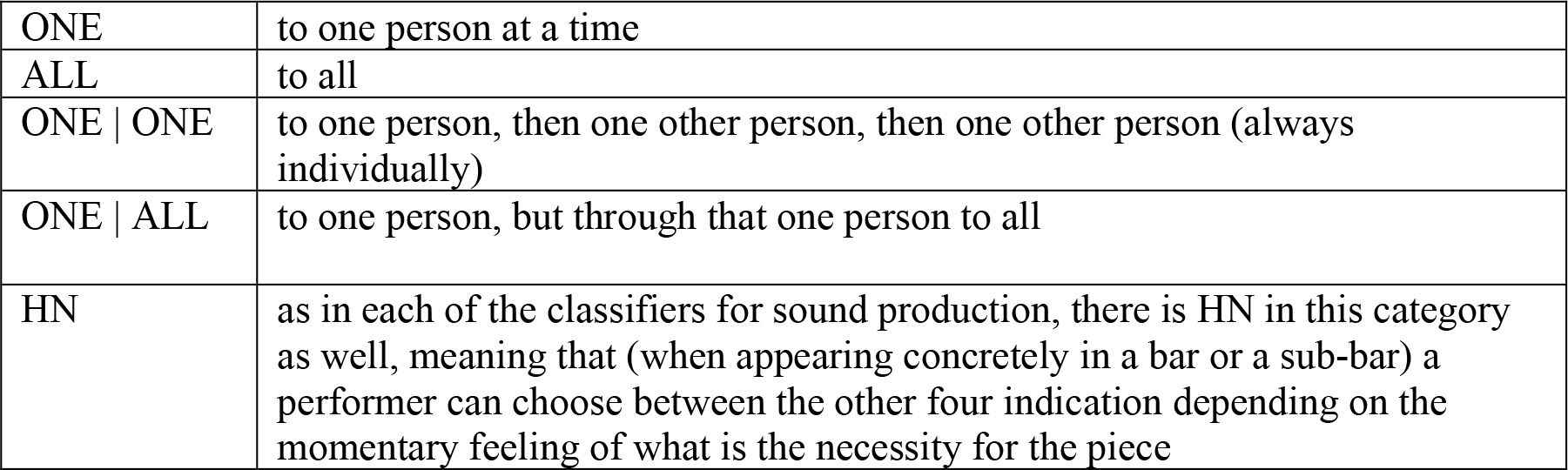

In his piece Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, Dario Buccino attempts to capture the weight of sound and its effects through several aspects. He constructs a scale of weighs, pressures, and speed that he categorises as the dynamic of movement and touch. These are part of the notation and technique given to the performer for execution – both in the area of the left-hand and the right-hand actions (figure 2.2.5). Furthermore, he differentiates between two sub-division of these parameters, for this argument especially important in the area of the touch in more particularly of the left-hand: one directed to the action to be made by the performer to the instrument in order to achieve sound, and the second one is a set of affection intentions of weight and sensations that are to be felt by the instrument from interactions and responses between the performer and the instrument, and the vibration of sound. The scale for the action-execution for production of sound goes as: extreme feather light, feather light, normal, heavy, extremely heavy, exceeding energy, substantial exceeding energy, extreme exceeding energy. Symbol ‘HN’ is a landmark of Buccino’s compositional practice and aspirations, and it refers to the moment of the performance. It is a direction for the performer to decide which of the possible options from the predetermined scale to use, determined by what the music demands in the very moment of the performance (figure 2.2.6). The scale for affections differentiates following degrees: extreme absence of pressure/contact, substantial absence of pressure/contact, zero pressure/contact, extreme magical contribution (c.m. stands for contributo magico), substantial magical contribution, magical contribution, extreme delicate, substantial delicate, delicate, violent, substantial violent, extreme violent, exceeding energy, substantial exceeding energy, extreme exceeding energy (figure 2.2.7).

Figure 2.2.6: Range of the weight of action in Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16

Figure 2.2.7: Range of the affection of action in Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16

Buccino has a specially dedicated “staff line” for the body, the endocorporeal staff (marked EC in the list of symbols, as seen in figure 2.2.5), where everything that happens to the body from the inner point of view and related to the sound (either as a source or reaction) must be incorporated in the moment of the performance. In addition to already described scale of affections, in endocorporeal he interplays also the directions for intention, adding three more steps to the scale: exceeding intention, substantial exceeding intention, extreme exceeding intention. Furthermore, the top line of this staff line, called Gratia, is dedicated to heightening the consciousness in the projection and sharing of the sound by giving indications whom to direct sound to (figure 2.2.8).

Figure 2.2.8: Explanation of subdivision of Gratia in Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16

Even though Buccino in the moment of writing the violin piece was not aware and therefore not aiming to apply nor “prove” any aspect of the theoretical studies mentioned, his compositional process intuitively engages with and alludes to the necessity of consciously thinking and including the mass of sound, especially through affections and endocorporeal thinking about the sound.[42] Buccino’s piece is an initial step in exploring the potentials this expanded thinking of mass and weight in the sense of what kind of weight the sound transfers and carries as it moves through space and time offers.

Figure 2.2.9: Interaction between the finger and the string's vibration

Examples featured in Figure 2.2.9 aim to demonstrate the interaction between the performer and the string's vibration, thus inciting the thought about how this feels and how imagining through tactile sensation can start to occur. The first example features a bowed open G string. The second example shows a close-up of the finger very lightly pressed on the string and captures the string moving the surface of the finger. The third example has a combination of different pressures of the finger. The camera frame is intentionally kept wide to capture the string's continuous activity on either side of the point of pressure in the moment of greater applied weight. There is a far greater scale of happenings in this interaction that is internalised in the moment of playing, with finesse and nuance beyond anything that can be captured with a video recording. This internalised vibration as a reaction to sound is the embodied knowledge from which a new palette of conceiving sound and interpretation can be created.

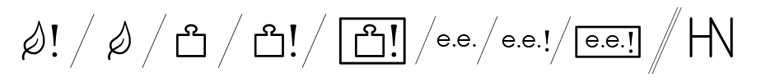

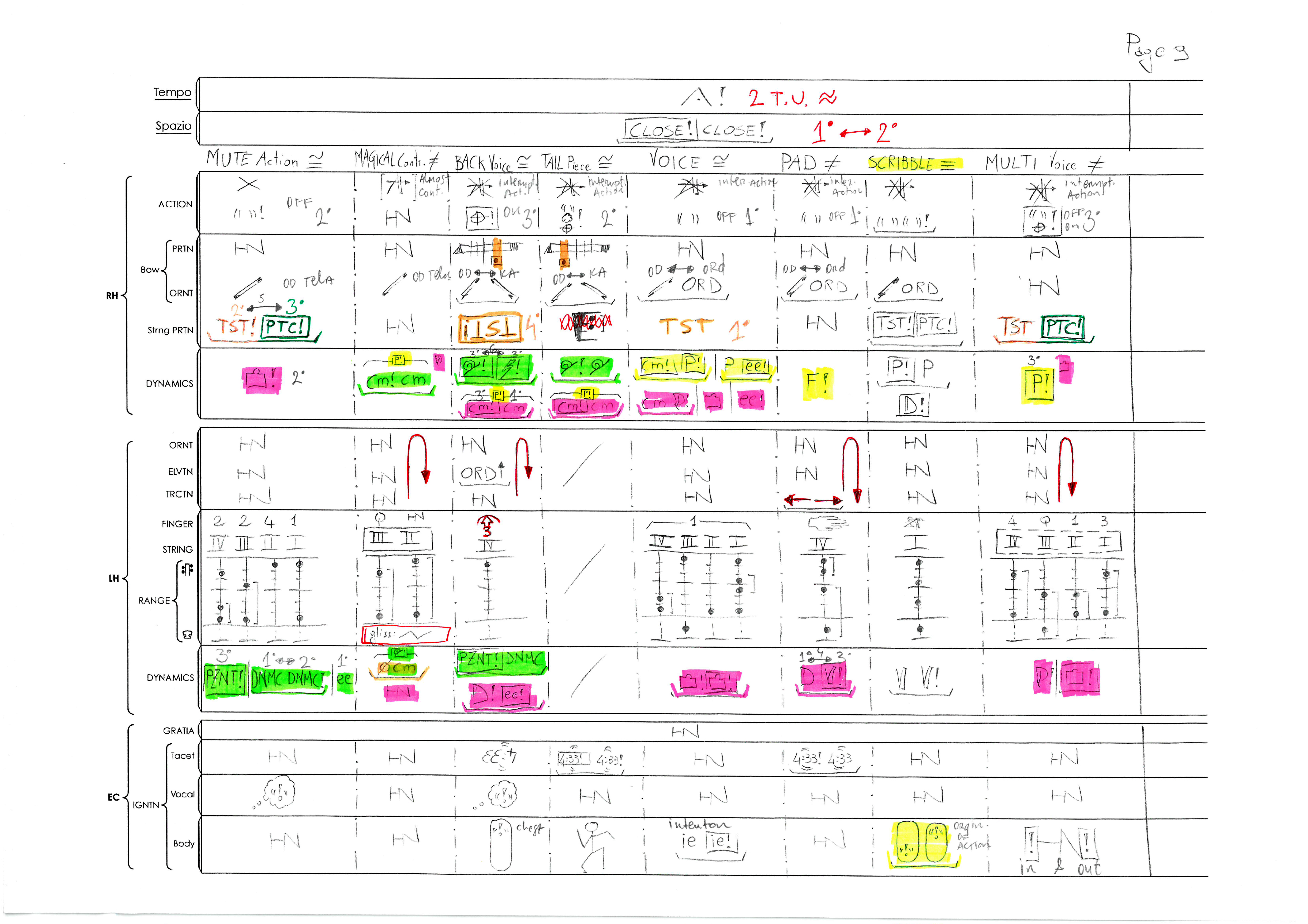

The extent with which Buccino develops his material into a music piece from the start requires the performer to think in minute detail about of every aspect of sound itself, of its relation to the bodily self, and of sound production, often simultaneously in parameters that even seem to be contradicting each other. The structure of the piece is such that one page of music represents one bar, and this bar has eight sub-bars (figure 2.2.10). The reading of the “bar” is not intended in a linear way, from left to right. Order of triggering of sub-bars is to be decided by the performer, in the moment of the performance. This already provides a large spectrum of possible executions on its own. But, added to this, in almost every sub-section, in each of the parameters there will be the appearance of HN. As previously explained, this notational symbol allows the performer to, while performing, call upon any of the predetermined options for each particular parameter of each instrumental identity (eight sub-bars are eight instrumental identities). For Buccino, the music is not in the score but within the score, and he says that the only way to play his music correctly is to play it incorrectly. This does not imply that the performer should deviate from the score, but that the ideal interpretation of the piece comes from incorporating all the detailed definitions (figure 2.2.5), scales and symbols through their meaning thus liberating the self to confidently navigate through the unpredictable, feeling and expressing the here and now. With all this, the interpretation flows between precisely notated and option-notated (by implementation of HN) resulting in unrepeatability. With the level and layers of sound and timber, combined with both care of felt, affection and “regular”-action relationship between the performer, the instrument, and the sound, there is a vast amount of possible unpredictable and even surprising outcomes that cannot be practised in advance. Although extremely sound-silence perception bound, the sound and gesture are never pitch bound. The notation is completely developed by Buccino, to accommodate and clearly convey all the details and nuances that the performer must consider and explore. For all these reasons, rethinking the origin of knowledge from which conception of the interpretation is drawn is almost paramount, and, in this case, because of its ever-changing structure, this process becomes a continuous moving state of imagining through felt and sensed through tactile.

Figure 2.2.10: Dario Buccino’s Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, page 9, annotated by the present author

The unpredictable outcomes of fast successions of two sounding events are not isolated as happening only in the case of Buccino, and in a larger sense can happen in interpretation of any piece. The difference being that the unintentional, intermediary sounds that can appear on some occasion for example in a shift of position or change of strings in a piece from a more standard repertoire even when performed by the same person, are the non-desirable accidents. They do not influence the “imagining”, as the performer “knows” what sound it has to aim for and must swiftly react to achieve it. In the case of Buccino, these “accidents” become also the elements that have to be considered as equal musical material – and in the moment of their appearance be recognised and utilised. They cannot be imagined in advance, as their existence will only arise in the moment of collision of the two concrete sound objects.

‘Don't look for traditional music or conventional things. Open your ears, your mind, and your soul without prejudice. Feel you are on another planet. If you can do this, it will be a big step forward in your own liberation. In Art, human nature can make leaps without intermediate phases.’ – Iannis Xenakis[43]

What ties together pieces as different as Finalmente il tempo è intero n° 16, The Su Song Star Map, Hauch, and other pieces from my focus repertoire is a need to rethink further how to conceive and imagine the sound and the piece’s entire outcome. In their essence, they demand expanding which source of embodied knowledge the imagination is drawn from. Emphasising “sensation-gesture-location” as thinking of the tactile conception of sound over a more habitual “location-gesture-sensation” imagining allows for an amplified experience of the non-forward-motional thinking about the work. This approach to the process further facilitates better understanding of spatial and textural consistencies and presence of the sound in space.

When giving conceptual metaphors related to perceiving through five external senses, Cox describes the five modes of knowledge as knowing is smelling, knowing is tasting, knowing is touching (and understanding is grasping), knowing is seeing, and knowing is hearing.[44] In the context of music and conceptualising, conceiving, and translating a music score into sounding, interpretation, and performance, the process of combining epistemological experiences of senses far beyond hearing makes that in music performance knowing is listening but with the body as a whole. Collection and assembly of the experienced in the mind as a possible outcome of an interpretation should include the “old fashion” imagining. The idea of conceiving sound from the score of the music piece beyond this habitual pitch-duration related knowledge is an attempt to broaden the way how to imagine the not-yet-heard. To conceive the outcome of the sound before it has been heard, a tactile sensation can be applied to any music, interpretation, and translation of any kind of notation, and not only to recent pieces. During the research, this became part of my conscious practice regardless of the repertoire. However, as it can be seen from the examples, pieces that are the focus of this research created the need to rethink and expand this practice more consciously. Cox advocates for ‘music’s power to elude the power of the eye and the hand.’[45] I would extend this thought with “the hand that touches” but not the overall tactile sensorial of the body as a whole and the sensory tool to collect and create tactile sound epistemologies.

- [1]Brandon LaBelle, Background Noise: Perspectives on Sound Art (London: Continuum Press, 2007), p.xi.

- [2]Robert Adlington, ‘Moving beyond Motion: Metaphors for Changing Sound’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association 128/2 (2003), , p.316.

- [3]Adlington, p.302.

- [4]Adlington, p.302.

- [5]Adlington, p.308.

- [6]Liza Lim, The Su Song Star Map, for solo violin. RICORDI. Sy.4794 (Berlin: Ricordi, 2018).

- [7]Aaron Cassidy, The Crutch of Memory, for indeterminate string instrument (any bowed, non-fretted instrument with at least four adjacent strings), Self-published, SKU:200402 (2004), p. 1, 2, 7, and 8.

- [8] Steven Connor, ‘The Modern Auditory I’, in Rewriting the Self: Histories from the Renaissance to the Present, ed. by Roy Porter (New York: Routledge, 1997), p.206.

- [9]Evelyn Glennie, ‘How to truly Listen’ ([TED Talk] (2003), https://www.ted.com/talks/evelyn_glennie_how_to_truly_listen [accessed 25 May 2023].

- [10]Arnie Cox, Music and Embodied Cognition: Listening, Moving, Feeling, and Thinking (Musical Meaning and Interpretation) (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2017), p.165.

- [11]Cox, p.168.

- [12]On page 164 of Music and Embodied Cognition, Cox describes that the touch of the tongue also plays a correlating role in the knowledge gathered with tasting.

- [13]For instance, Roger Woodward writes “I had assimilated the whole score in my mind's eye and musician's inner ear through analysis. Before I sat at the piano for the very first time, I felt that I knew the work sufficiently well and that it was, at least in many ways, already a part of me. I heard the opening ten bars even before I sat down to place my hands over the pitches themselves and bring to life the musical event of which they formed part”, see Roger Woodward, ‘Preparations for Xenakis and Keqrops’, Contemporary Music Review, 21.2-3 (2002), p.114.

- [14]In their study of incremental comprehension of reading novel musical material, Hadley, Sturt, Eerola and Pickering suggest that "during initial processing, musicians comprehend notation in terms of contextual musical relationships, as opposed to simple performance instructions." see Lauren V Hadley, Patrick Sturt, Tuomas Eerola, and Martin J. Pickering, ‘Incremental Comprehension of Pitch Relationships in Written Music: Evidence From Eye Movements’, Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 71.1 (2018), 211–219.

- [15]John Baldessari, ‘Artist: John Baldessari’ https://www.saatchigallery.com/artist/john_baldessari [accessed 22 May 2023].

- [16]Sabine von Fischer, ‘A Visual Imprint of Moving Air: Methods, Models, and Media’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 76.3 (2017), 326-348.

- [17]Jerrold Levinson, ‘What a Musical Work Is’, The Journal of Philosophy, 77.1 (1980), 5-28.

- [18]The idea of the score as a ‘first space’ is discussed in chapter 2.1. [Please see full Thesis, available via University of Huddersfield's repository.]

- [19]For instance, exceptionally potent example for this can be heard in ‘Triadic Memories’ [Disc 3 and 4] of Morton Feldman Piano box set, released by Another Timbre. See Feldman, Morton, ‘Triadic Memories [Disc 3 and 4]’, Morton Feldman Piano, Philip Thomas (Another Timbre, at144x5, 2019).

- [20]Philip Thomas in Morton Feldman, Morton Feldman Piano, Philip Thomas, liner notes (Another Timbre, at144x5, 2019), p.6.

- [21]Examples for this come from Clara Iannotta’s and Aaron Cassidy’s pieces, and “glissando” in particular, and this will be described in more detail later in the text.

- [22]In conversation with the Philip Thomas, 6 October 2020, Huddersfield/Brussels.

- [23]Morton Feldman Piano, pp.11-12.

- [24]Roger Woodward, ‘Preparations for Xenakis and Keqrops’, Contemporary Music Review, 21.2-3 (2002), p.117.

- [25]Rebecca Saunders, Hauch, Edition Peters EP 14345 (London: Peters Edition, 2017)

- [26]Saunders, Hauch.

- [27]This has been hinted also by Rebecca Saunders herself during our work session on the piece, which took place on 18 January 2020 in Berlin.

- [28]This table contains a mixture of explanations found in the score, information received while working with Saunders, as well as listening to her talks.

- [29]Saunders, Hauch.

- [30]In conversation during the working session with the composer, 18 January 2020, in Berlin.

- [31]Saunders, Hauch.

- [32]Saunders, Hauch.

- [33]Lim, The Su Song Star Map, in performance notes.

- [34]Lim, in performance notes.

- [35]Gesture and physicality as material is discussed in detail in chapter 4.2. [Please see full Thesis, available via University of Huddersfield's repository.]

- [36]Cox, p. 172.

- [37]Geographical distance understands the violin, and in this case more specifically the fingerboard, as a mapped terrain.

- [38]Furthermore, certain existing recordings currently circulating can be even misleading, as in some cases the misinterpretation of the bow placement as well as paper clip placement produces a completely different sound. In this respect, it could be argued that the score itself could provide further precision on some aspects, for example placement of the bow, that could possibly render obsolete this kind of mishaps. These matters are discussed further and in detail in chapter 4.1. [Please see full Thesis, available via University of Huddersfield's repository.]

- [39]More detailed about The Crutch of Memory and on gesture as material is discussed in chapter 4.2. [Please see full Thesis, available via University of Huddersfield's repository.]

- [40]Alberto Nicolis and Riccardo Penco, ‘Mutual Interactions of Phonons, Rotons, and Gravity’, Phys. Rev. B, 97.13 (2018), 134516 and Angelo Esposito, Rafael Krichevsky, and Alberto Nicolis, ‘Gravitational Mass Carried by Sound Waves’, Phys. Rev. Lett., 122.8 (2019), 084501.

- [41]Buchanan, Mark, ‘Sound Waves Carry Mass’, Physics Magazine (2019), https://physics.aps.org/articles/v12/23 [accessed 22 May 2023].

- [42]Consciousness of weight, dynamics of movement and touch for sound, as well as endocorporeal aspects of playing are part of Buccino’s compositions since the mid 1990s.

- [43]Woodward, p.109.

- [44]For more on metaphor ‘knowing is seeing’ see: George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980). For more on ‘knowing is hearing’ see Cox, pp.164-165.

- [45]Cox, p.173.