2.1 Score as First Space: understanding the gap between what is and what is not in the score

‘Differentiate between creating a language in order to say something and evolving a language in which you can say anything.’ – Cornelius Cardew[1]

During my Masters studies my approach towards the score started shifting away from a positivistic view towards searching for my own personal approach.[2] This change was prompted mainly by scores which challenged the norms of Western classical notation, which were increasingly becoming the focus of my repertoire. I needed a way to enter and understand a piece through the score to find my path for playing it.

As a performer, I always ask what all the aspects are that lead to performance: what are the temporalities which the piece enacts, and, especially, what are the spaces in which the piece exists. In my practice, the first “time-space” of the piece I must inhabit became the score itself.[3] I started seeing the score as a three-dimensional space, a habitat that is a meeting point between the music, the composer, and myself, a place that I must learn to feel “at home” with, and whose notation is my map. Thus, the score became the first space.

To create an interpretation is to create a translation of a text. All notation is graphic. While graphic notation that uses drawings or other non-musical symbols to annotate musical scores exists as a category, in all the other forms that music notation uses, graphic symbols are an alphabet of notation. Graphic symbols hold meanings of sound and emotions while navigating between the parameters of what can be notated and ‘what cannot be notated’.[4] While Brian Ferneyhough considers the score as a ‘cultural artefact with an aura of spiritual resonance’,[5] Ian Pace suggests that a musical score can be seen not as a prescriptive text telling a performer what to do, but rather as ‘delineat[ing] the range of possible performance activities by telling the performer what not to do’.[6] The ‘musico-cultural context’[7] that surrounds a specific piece might give the impression that the ‘suggestion’ is not a suggestion but direct instruction, but as Paul Roberts points out, there are lingering questions about what it means to be expressive with the notes and give expression to the notes written in the score.[8] In relation to my focus repertoire, I found it often depends on the context. Sometimes, and in the case of older and previously performed pieces, the context is somewhat easier to grasp. In the case of less performed and especially unperformed pieces, the context might be obscure, and must be gathered and built.

Approaching the pieces from my research repertoire for the first time, I read each score closely to discover every annotation, every event that is a sound object, locating its place and time, connections and relations to other objects in this space; discovering sometimes distant relationships across the space, and time, that enable finding the smallest particle of music-carrying event that has information on both what to do and what not to do. Spending time with the score in this manner means, for me, time to get to know and learn about the composer, their past and perhaps potential future, the music contained in the piece, and to situate myself in relation to them. It is an intimate space where trust and dedication are paramount. A close reading of a score is not a contained instance but a process. This practically flat object, a piece of paper, is a multidimensional volume with depths and occupied and unoccupied spaces. Considering the score as a multidimensional space in which some objects are objectively present (through symbols used to depict them) and some seem absent, due the nature of notation having limitations to notate every detail about sound, it is the understanding of the reading as an ongoing process that allows for these “non-present” objects to also appear. While the description of this approach to the score is a conceptual abstraction, the process itself is one of intimacy and proximity, which demands engagement and a desire to leap. There is no fixed approach, no recipe to follow; rather, the methodology and process mould themselves in relation to a specific score. Reflecting on my practice, I can detect elements that recur with each piece – not necessarily always in this order:

- ◦ Take time to sit with the score. Silence is desired, if not paramount. In case of not having silence, develop focused and active “non-listening” and filtering out of the sounds of the environment.

- ◦ Take time to carefully read both performance and programme notes, where provided.

- ◦ Read the performance notes while comparing the corresponding and specific appearance(s) of that action in the score, especially in cases where the legend is placed before the beginning of the piece (and no information is written above the stave).

- ◦ Converse with the composer when needed and when possible.

- ◦ Start assembling my first space, being especially attentive to object placement in cases where composers employed spatial organisation.

The importance of understanding the score itself as the first space was, for me, particularly strong and relevant in the case of the Freeman Etudes. The first ‘given’ which was constitutive for this work, and probably the most grounding element of this otherwise extraordinarily detailed yet completely non-linear music, is the spatial structure (the layout of the score).[9] Cage’s parameter of the spatial organisation for the notation of the piece established that the score for each etude was to have twelve systems of music, with a length of 9.6 inches per system.[10] In this predetermined space, the first layer of composing was dedicated to choosing individual pitches as a point traced on to paper from Antonín Bečvář’s Atlas Australis 1950.0. A performer must not only translate each individual sounding event but try to portray this “space”. When I say non-linear music, this is because although there is a linear passing of time, each note is indeed a completely individual sounding event: like stars in the sky, each carrying its universe with it, all distant and scattered in vast space, yet sometimes as one looks the night sky is perceived as so close that they ‘overlap, giving the effect of a near-continuous sheet of light’.[11] Considering the score through the metaphor of outer space helped me read all the technical elements and difficulties that the piece poses for the performer as a constellation of relations and helped me bring this chance-travel through outer space to the audience. First, I would approach technically honing and sonically understanding each sound event (each note with all its attributes), and in this process I would focus on how this sound feels in the hand and what is the relation between the hand and the instrument. In the following step, I would connect each sound event to its immediate neighbouring events. Similarly, while listening to changes occurring in the sounding outcome, I would also focus on the inner body feeling of this sound and relation of the hands to the instrument. The more I focused on the physicality between the gesture and the instrument, the more accepting and less disturbing the unexpected sonic “parasites” became. In this process where I started shifting the focus on to learning physical distances and feeling the space travelled in the hand, a note, one pitch, became a location on the fingerboard, a physical coordinate which the hand must reach. Contrary to my initial belief that shifting focus away from aiming for one sound a pitch has to produce would result in less precision, this process of work yielded more successful execution.

While performance notes carry indispensable clarification about symbols, the programme notes written by the composer (when accessible) can provide equally indispensable information, helping to understand the infamous element of what is not possible to notate and giving context to all the technical parameters.

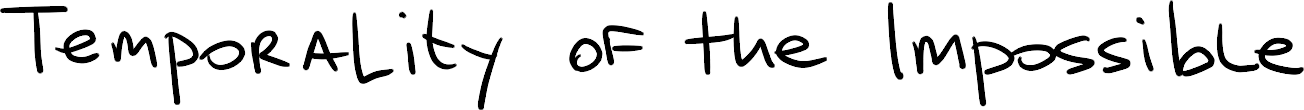

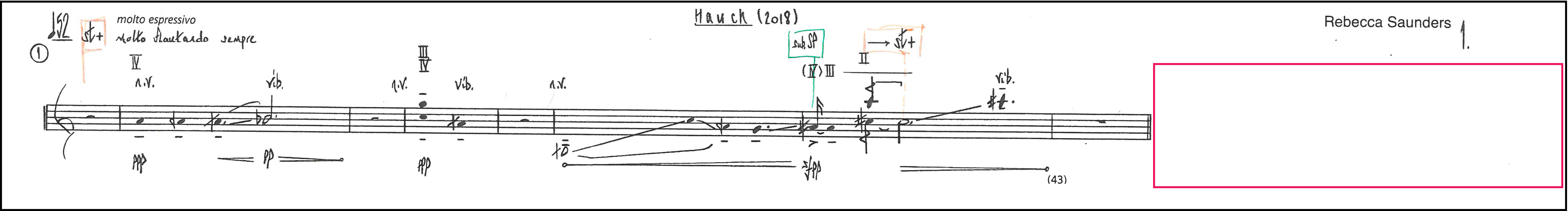

Rebecca Saunders’ comments, in relation to her piece Hauch, that ‘silence is the canvas’ and that the ‘bow is drawing out the sound out of silence’ reinforce the presence, notion, and understanding of the empty spaces after and between phrases on the layout of the page (figures 2.1.1 and 2.1.2).[12] These details for me enhanced the process of navigating through the score, finding the pace and the way of breathing, and finding the beginnings of the sound before it physically and perceptibly appears.[13]

Figure 2.1.1: Excerpt from Rebecca Saunders’ Hauch, with focus on the empty space after the first phrase

Figure 2.1.2: Excerpt from Rebecca Saunders’ Hauch, with focus on the empty space between the third and the fourth phrase, and after the fourth phrase

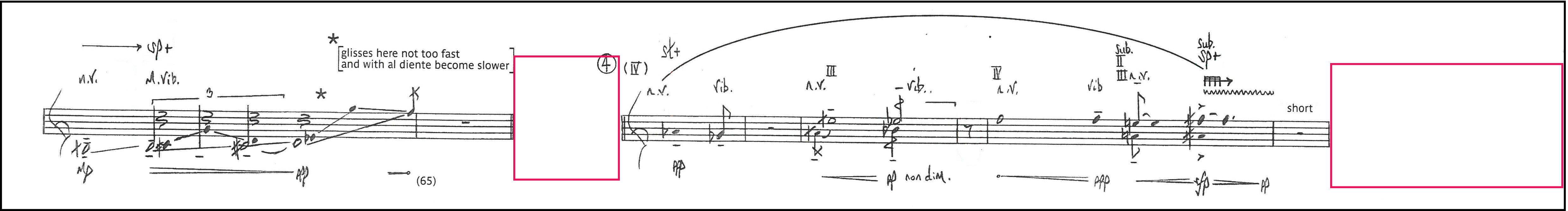

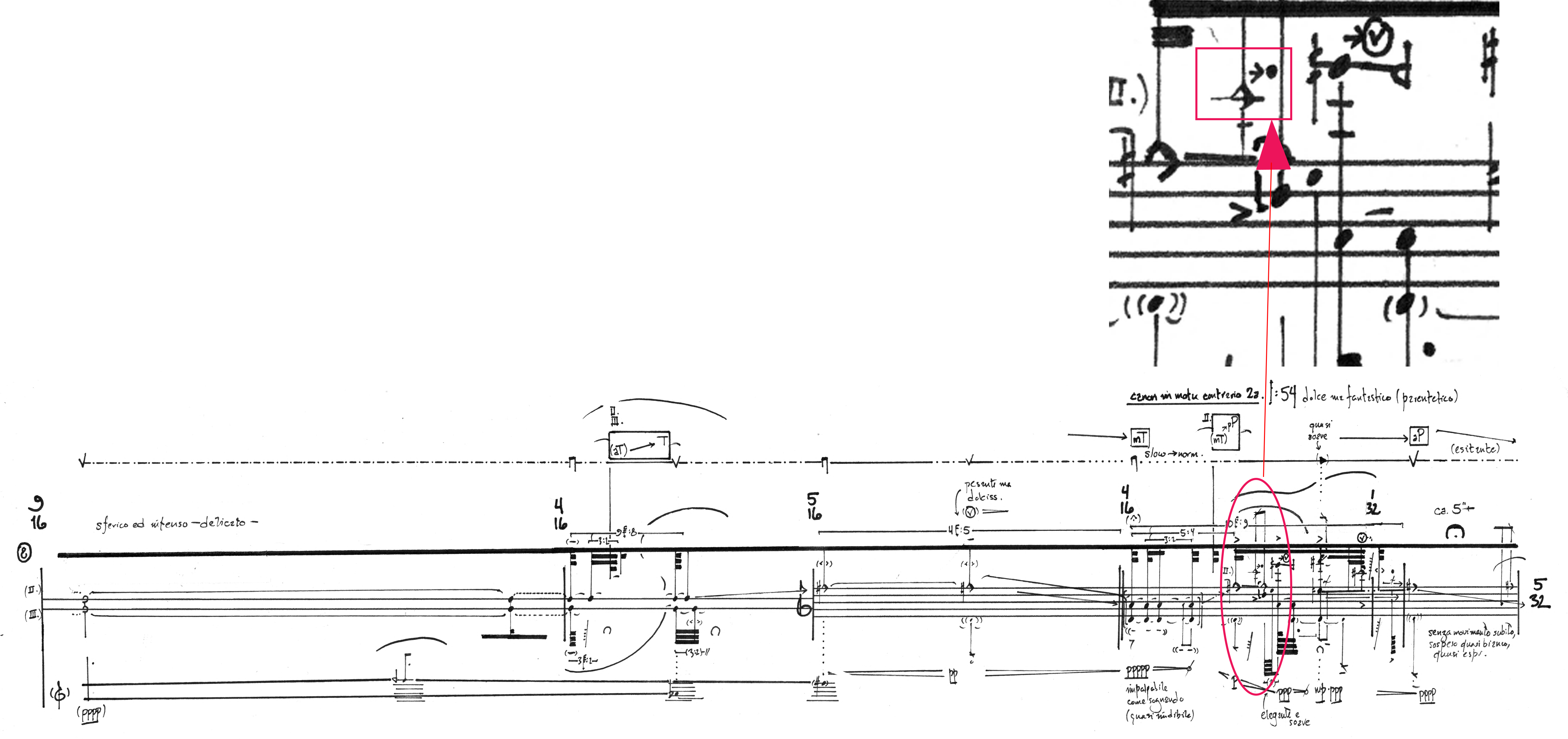

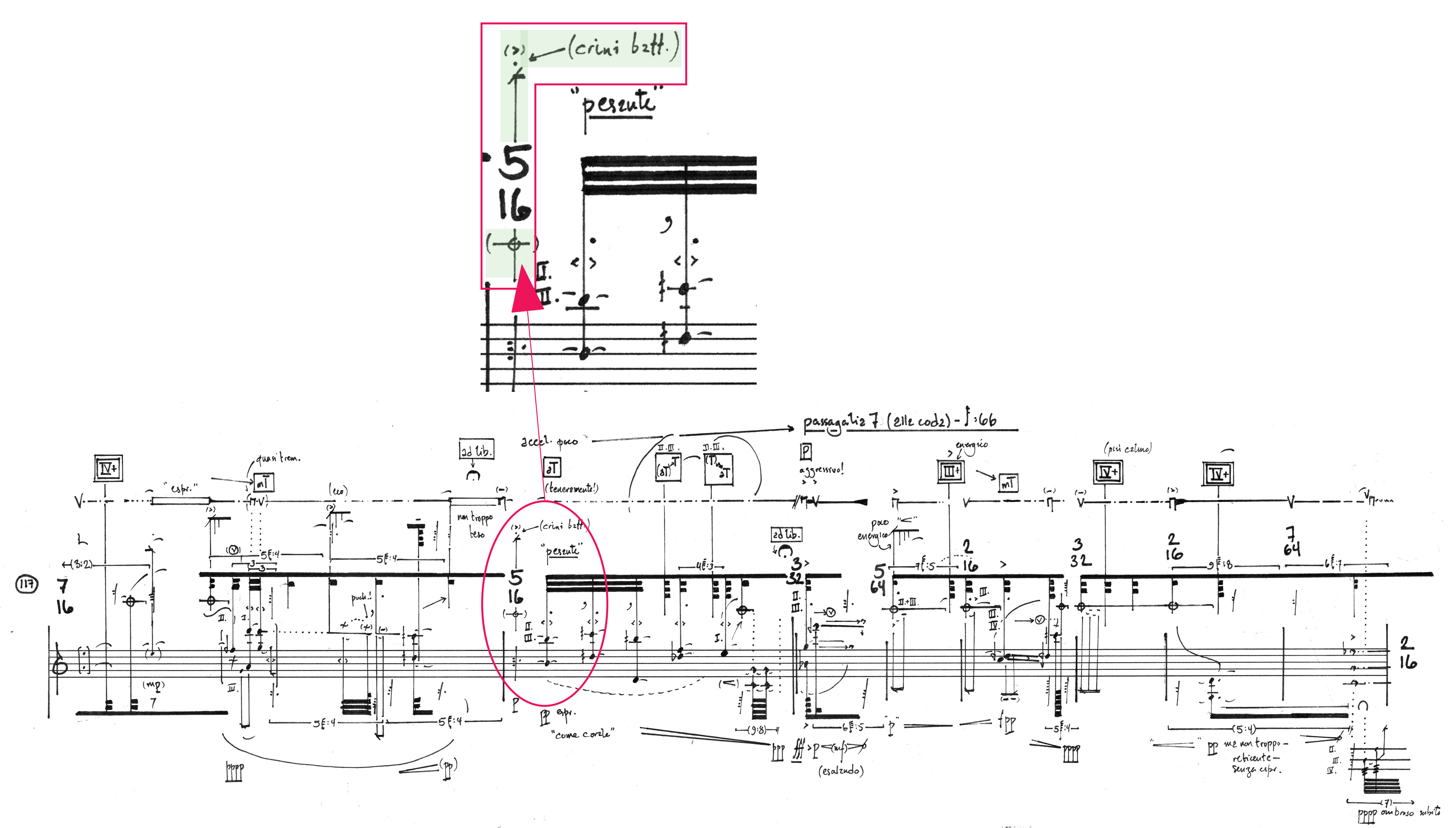

In his programme note for Wolke über Bäumen, Evan Johnson says that the link, although he offers one, between Paul Klee’s crayon drawing of the same name and the piece ‘isn’t entirely clear’.[14] However, for me, his description of the drawing as ‘a sinuous, snakingly horizontal nest of a line above a jagged, chaotic, but equally horizontal forest of sharp angles’ provides a strong imagery from which to start building a space,[15] and imagery, moreover, that corresponds quite closely with the way the handwritten score looks. Johnson’s manuscript score feels as if it is the piece’s diary. Dense tiny writings at times needed enlargement in order to decipher the elements present in a sound object, often bringing a discovery that there was in fact a further object in there. Figures 2.1.3 and 2.1.4 show just two of many such instances: in bar 11, the indication of change of pressure of the left-hand finger and in bar 118 the appearance of the only crini batt. (crini battuto bow stroke) of a muted string, which is somehow inconspicuously hiding in plain sight, obscured by the barline, time signature, and pause. Wolke über Bäumen is one of the pieces where, because of the complexity and dense writing, it is necessary to comparatively go through the performance notes and sounding objects. In doing so, relationships between these objects fall into place, and this obscure unknown space evolves into a familiar time-space, in which I can start to move.

Figure 2.1.3: Evan Johnson’s Wolke über Bäumen, bar 11

Figure 2.1.4: Evan Johnson’s Wolke über Bäumen, bar 118

Inhabiting Hauch placed me in a vast, foggy space which seemed to be breathing on its own. As I would start to move and get closer to the sound objects, this veils of silence would start to disperse, its residues still obscuring the clear apparition of the sound. The score for Johnson’s Wolke über Bäumen was a forest interspersed with patches of erased space in which silence vibrates. This space became a forest not due to the word ‘trees’ (Bäumen) in the title but rather because of the elongated upwards and downwards stems whose notes and beams create flourishing canopies and also reveal complex networks of communication through their roots. This imagery fueled the imagining of the felt sound, that all contributed to finding movements, gestures, an appropriate relationship with the instrument when playing. It directly influenced how I approached searching for sound characters, adjusting bow placement and speed along the way. The way I used my left hand went through similar processes of exploration: flatness or roundness of the finger, portions of fingertips touching or gliding over the string, speed of movement (especially for glissandos or glissando-like movements of the left hand), finger pressure (not only between harmonic or normal pressure, but also within each of these categories), balancing pressure on adjacent strings to allow a more usable portion of string over fingerboard for the bowing.

This approach is an abstraction of an already abstract concept of putting sound on paper. But, for me, this process of thinking turns a flat piece of paper into a three-dimensional space in which I feel I am gaining better insights into the spatiality of the work, its sound identities, their positions, and relationships. A place from which I can start to imagine the interpretation, what might be its potential sounding or potential physical movements (a specific contemplation about source of imagination is discussed in more detail in chapter 2.2, and I elaborate further about my conceptualisation of physical movement as material in chapter 4.2), all together bringing me closer to finding my way in how and what, in a practical sense, I have to do to play the piece.

- [1]Cornelius Cardew, ‘Notation: Interpretation, etc.’, Tempo, 58 (1961), p.22.

- [2]Ian Pace, ‘Notation, Time and the Performer’s Relationship to the Score in Contemporary Music’, p.152.

- [3]Cardew, p.22.

- [4]Paul Roberts, ‘The Mysterious Whether Seen as Inspiration or as Alchemy: Some Thoughts on the Limitations of Notation’, in Sound & Score: Essays on Sound, Score and Notation, ed. by Paulo de Assis, William Brooks, and Kathleen Coessens (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2013), p.33.

- [5]Brian Ferneyhough, ‘Interview with Richard Toop’, in Collected Writings, ed. by James Boros and Richard Toop (London: Routledge, 1998), p.272.

- [6]Ian Pace, ‘Notation, Time and the Performer’s Relationship to the Score in Contemporary Music’, p.153.

- [7]Jerrold Levinson, ‘What a Musical Work Is’, The Journal of Philosophy, 77.1 (1980), p. 13.

- [8]Paul Roberts, ‘The Mysterious Whether Seen as Inspiration or as Alchemy’, pp.37-38.

- [9]Pritchett, ‘The Completion of John Cage’s Freeman Etudes’, p.266.

- [10]For more detail on John Cage’s Freeman Etudes see chapter 1.2. [Please see full Thesis, available via University of Huddersfield's repository]

- [11]James B. Kaler, Cosmic Clouds (New York: Scientific American Library, 1997), p.2.

- [12]Rebecca Saunders, Hauch, performance and programme notes, Edition Peters EP 14345 (London: Peters Edition, 2017).

- [13]Hauch is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.2. [Please see full Thesis, available via University of Huddersfield's repository]

- [14]Evan Johnson, Wolke über Bäumen, (self-published, 2016), performance notes, p. i.

- [15]Evan Johnson, Wolke über Bäumen, p. i.